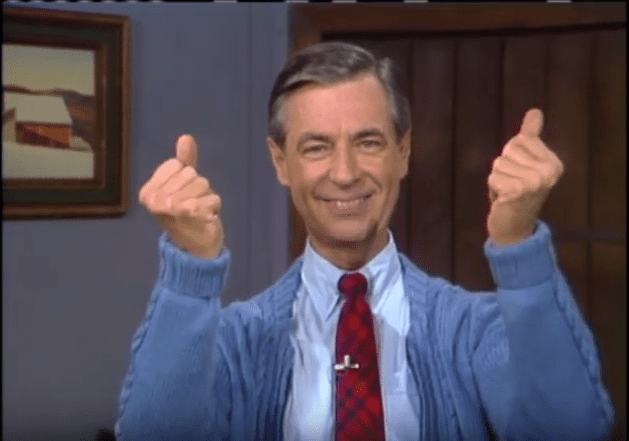

Fifteen years ago today we lost Mister Rogers. Presbyterian minister. Puppeteer. Television friend and neighbor.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eInUUfyqa5o

I was then a sophomore at Baylor, not quite 20 years old, and only beginning to understand the sense of loss one finds when the familiar elements of childhood pass away. But unlike when other famous people died, this one felt strangely personal, as if I’d lost a treasured childhood friend. As a child in a cold, unfamiliar, and ominous world, I found Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood to be that safe place, where my honest questions weren’t spurned, where my imagination was fostered, and authenticity was expected.

You might say that the Neighborhood was my first real experience with the concepts of ritual and liturgy. Even as a little child, I would sit down at the appointed time, sing along while pretending to trade my jacket for a sweater and my dress loafers for some well-worn sneakers. I would be led through playful rituals of substance and symbol which helped me understand a little better the world and my place in it. At the end, Mr. Rogers would send me back into that big, scary world with reminders of my own personal worth and a sense of purpose.

Fifteen years later, I’m a parent myself, and with rare exception MRN is the only show we allow our three-year-old to watch. And I’m watching all over again with him.

Christian culture and the slick, distracting, disorienting worship it produces is the anti-Neighborhood. It’s more like the endless, mindless string of Warner Bros. cartoons, good at capturing attention, eliciting a few laughs, but leaving a greater void than was there before. And pretty soon, it’s not enough. Then you have to jack up the volume higher and make your scenes shorter and your dialogue quicker. Maybe that’s why Christian worship has seemingly forfeited any spark of creativity, preferring instead to ride the all-powerful waves of commercial entertainment.

I have a colleague here on Patheos who fancies himself an innovative pastor because he’s figured out how to leverage such secular entertainment to get butts into his “unique” congregation, which actually bears a striking resemblance to all the thousands of Wal-Church franchises dotting the American urban landscape.

Mister Rogers was alternative, not just a cheap copy of other children’s media that tried to teach a few lessons, but a real, authentic alternative. Instead of cheap laughs, short bursts, and visual thrills, he insisted on refined, carefully crafted scripts, honest conversation, and relentless confrontation of tough subject matter. The homemade sets, threadbare puppets, and complete lack of special effects were simple yet symbolic; they honored the viewer’s innate tendency toward creativity and imagination. And when it was time for pretending, that was clearly delineated by a trolley’s daily transformation from a living room toy into a vehicle for mass transit in the Neighborhood of Make Believe.

Then there’s another of my Patheos neighbors, we’ll call him “Mark Driscoll.” He says it’s all about Jesus when it’s really all about the macho-posturing masculine warrior-god he’s created in his own disordered, insecure, barrel-chested image. With a He-Man hermeneutic and an easily-offended male dignity, “Pastor” Mark is the ultimate jesusy rock star, procuring roadies out of Christian culture’s celebrity worshipers.

Mr. Rogers was clearly the guide, the adult in the conversation, but he was not a star, a celebrity, or even an actor. He didn’t seem to have an inflated sense of self-worth or any illusions of grandeur to defend. He was just himself, a person, a fellow human who dignified the feelings, concerns, and creativity in children that others often ignored. dismissed, or even ridiculed.

These are the things Christian worship must be for the church and society. It’s got to be a real alternative, almost a diametric opposite of the saccharine and substanceless commercial entertainment. Its job isn’t to distract believers with good feelings. It’s supposed to remind us who we are and in Whose story we play a part. Its songs aren’t to transport us to a trance-like meeting with deified emotions, but to ingrain in us the many ways in which God has chosen to say “I love you,” and that God can love us just as we are. Its words and sacraments aren’t just to make us feel good for a time, but to fill us, mold us and empower us to be God’s prayer for the world.

The refined and elegant words of the church’s liturgy are not a self-important system of smoke and mirrors. No, they are riven, saturated, and caked with powerful, eternal significance. That’s what happens when your worship is not a passing “style” to entertain you, but is backed by an eternity of truth, honesty, and authenticity.

Like Rogers expected of his young viewers, liturgical worship expects more of the church. It assumes that we are indeed the thoughtful, imaginative people our good God created us to be. You’re expected to not merely sit back and relax, but to listen. To receive with open minds, open hearts, and open hands what the Spirit would impart to you.

May the church’s worship once again be less like the darkness around us, and more like Mister Rogers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xDRbhH2RH7o