I was quite moved by Thorn Coyle’s recent post, Disturbing the Peace, because she put her finger on something that has been itching at me for some time.

In her blog post, Thorn declined the invitation I took, earlier this month, to write something about best practices for peace.

“Organizing with Black leaders and communities of color affected by police militarization and systemic harassment and imprisonment has diminished my talk of peace,” she wrote. “Talk of peace can be used to stifle anger… Talk of peace can all too often wish to rush toward niceness, toward a balance that doesn’t exist, and toward a veneer that will soon crack. Before there can be peace, there must be justice.”

Short response: Boom. Nailed it.

Longer response: I’m reminded of John Woolman, the great 18th Century Quaker advocate against slavery, who worked tirelessly to remind Friends of exactly this point, when he wrote, “Oh, that we who declare against wars, and acknowledge our trust to be in God only, may walk in the light and therein examine our foundation and motives in holding great estates! May we look upon our treasures, and the furniture of our houses, and the garments in which we array ourselves, and try whether the seeds of war have nourishment in these our possessions, or not.”

With the exception of the invocation of a monotheist deity, Woolman is speaking directly to my condition. If I declare myself a proponent of peace, I have the obligation to look at how my privilege, my part in the machinery of injustice and inequality, is itself one of the causes of war and violence.

Mouthing nice phrases about peace is not it!

Peace work is not just protesting against war, or, worse, attempting to stifle violence where it appears as an attempt of the voiceless to cry against injustice.

Peace isn’t just the absence of overt violence. It is the promotion of justice, and the end of covert violence, like poverty, racism, and homophobia, and a refusal to quietly accept privilege that has roots in those forms of violence. Peace work is justice work, and it must be waged, actively, not simply requested, nicely.

I have been increasingly troubled, these last few weeks, as protests continue within the Black Lives Matter movement, by the number of whites I have encountered who seem to spend all their time combing reports and videos of protest marches, looking for anything and everything they can identify as “violent” in order to attempt to discredit the movement for justice.

I actually saw one story, which reported on counter-demonstrators at a rally in support of the Ferguson Police Department having popped blue balloons as an incident of “black violence.” The mind boggles. Black men and women are dying in the streets, but popping balloons is an expression of violence?

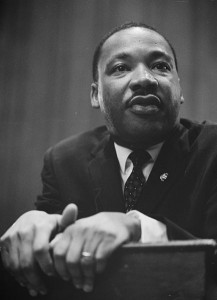

I’ve lost count of the number of white critics who have had the arrogance to invoke Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy of non-violence in an effort to shame the protesters in the Black Lives Matter movement, and in the Reclaiming MLK marches last week.

“I mean seriously, this isn’t the protests of MLK. He would hate this,” one white commenter wrote. “He loved.”

“He loved.” Well, I believe he did. But that doesn’t mean he would have wanted protesters to be too nice to discomfit the complacent, or to disrupt business as usual within a society still running full bore on institutionalized racism.

I love my child. Which never translated into telling her to be quiet when she was ill or injured, or not confronting bad behavior with strong words and strong consequences. And while I wouldn’t lie to you and say that my loving parenting always looked like a Mother’s Day card or that I never made mistakes–embarrassing ones–I also know too much about love to think that it always looks pretty.

Love is a passionate business. Sometimes, it’s loud. Especially when there is real danger, and real harm, sometimes it can be very loud indeed.

Contrary to what condescending white Americans may want to believe, the love King was talking about wasn’t always a Hallmark greeting card version of love, either. And as for his non-violence, it was a hell of a lot more nuanced than, “Don’t swear, don’t shout, and don’t pop the other guy’s–literal–balloons.” Actually, when asked to condemn riots on the part of African Americans of his day, he said,

It is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.

Both King and Woolman understood something that too many whites who are upset about the current wave of racial unrest fail to understand: peace is not a matter of stillness, and particularly, it is not a matter of dissent suppressed.

Rather, peace, real peace, is an active force, constantly on the lookout for quiet violence as well as the use of weapons and force. Poverty is violence. Racism is violence. Relegating women, or gays, lesbians, and the transgendered to lesser lives–that is violence. Colonialism is violence.

And at times, the very calm that would outwardly seem to those in comfort to be the essence of peace, is instead simply another form of violence.

Peace is effortful. Peace will involve struggle. And though I would never agree that violence is necessary to reach it, I would very much agree that, “No justice, no peace.”

Let’s reach toward justice. Let’s reach toward peace–real peace–and never settle for the hush of censored Truth.