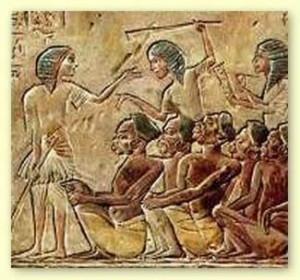

This past weekend Jews throughout the world celebrated the beginning of Pesach, the Passover holiday, by embarking on the ancient rituals of the seder. The seder, with its rich symbolic actions and accompanying powerful text from the Haggadah, is an entryway into the psychological, emotional and spiritual experience of the Exodus. Indeed, this is the very point of having the seder, as the early rabbis taught: “In every generation, one is obligated to see oneself as having left Egypt. (Pesachim 10:5)” What does this immersion into the Exodus narrative cultivate in a person? What sort of world outlook does this bring forth?

This past weekend Jews throughout the world celebrated the beginning of Pesach, the Passover holiday, by embarking on the ancient rituals of the seder. The seder, with its rich symbolic actions and accompanying powerful text from the Haggadah, is an entryway into the psychological, emotional and spiritual experience of the Exodus. Indeed, this is the very point of having the seder, as the early rabbis taught: “In every generation, one is obligated to see oneself as having left Egypt. (Pesachim 10:5)” What does this immersion into the Exodus narrative cultivate in a person? What sort of world outlook does this bring forth?

If one examines the story from a simple reading it becomes clear that the Exodus is about the miraculous. It is about God emerging to shape the fate of humanity in the most dramatic, supernatural and awe-inspiring way possible. It is about frogs falling, rivers turning red with blood and impenetrable veils of darkness. It would seem to inspire people who delve into this story to be miracle-seekers; ever yearning for the Divine to uplift, rescue and mold the course of human history. This, however, is simply the surface reading.

In the beginning of God’s involvement in the plight of the Israelites, God turns to Moses and makes a remarkable statement in Exodus 6:2-3:

ב. וַיְדַבֵּר אֱ־לֹהִים אֶל מֹשֶׁה וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו אֲנִי יְ־הֹוָ־ה

ג. וָאֵרָא אֶל אַבְרָהָם אֶל יִצְחָק וְאֶל יַעֲקֹב בְּאֵל שַׁדָּי וּשְׁמִי יְ־הֹוָ־ה לֹא נוֹדַעְתִּי לָהֶם2. God spoke to Moses, and He said to him, “I am the Lord.

3. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob with [the name] Almighty God, but [with] My name YHWH, I did not become known to them.

It is within this very early stage of the story development that God introduces us to a different aspect of His existence. Each name of God reveals a unique characteristic of how we, as people, relate to Him. Additionally, this new name was not held back from the forefathers purposefully (which would have been הודעתי in Hebrew) but rather they did not come upon it themselves (נודעתי).

Rashi commenting on these verses states that God’s enduring faithfulness was never experienced by the patriarchs because, while God made promises to redeem their descendants from servitude, they never lived to see that day fulfilled. However, this explanation and the verses themselves are quite difficult to understand because we do have instances of the patriarchs interacting with God using the tetragrammaton (Genesis 16:7 and Genesis 22:14). How then could the Torah claim that this was a name and an aspect of God only now being revealed for the first time to Moses?

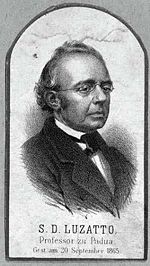

The 19th century Italian Jewish thinker, Shmuel Dovid Luzzatto, offers an insight that reflects well on the objective of the seder experience and the world outlook it strives to cultivate. Luzzatto in his commentary points out the earlier instances of the use of this  Divine name and insists then that there is another layer of meaning present here beyond the obvious one, for it is clear that the forefathers did have knowledge of this name. Rather, Luzzatto teaches that what the forefathers did not fully come to terms with was the combination of the various names of God, representing several unique Divine attributes, at the same time. In certain moments they accessed one manifestation of God and at other moments, a different manifestation of God, but never the combination.

Divine name and insists then that there is another layer of meaning present here beyond the obvious one, for it is clear that the forefathers did have knowledge of this name. Rather, Luzzatto teaches that what the forefathers did not fully come to terms with was the combination of the various names of God, representing several unique Divine attributes, at the same time. In certain moments they accessed one manifestation of God and at other moments, a different manifestation of God, but never the combination.

It is this combination that Moses and the Israelites in Egypt experienced firsthand. Luzzatto teaches that the tetragrammaton is the mode of an all-encompassing Divine creative capacity: “I bring forth the goodness and the wickedness, and I want Israel to know that the wickedness, along with the goodness, come from me.” There is no bifurcation, no separation of the source for suffering and the source for joy in this world. The potential for either are both created by God. This stark truth brings a person to a certain sense of realism. One cannot ascribe any particular injustice or justice to any other supernatural source. Indeed, one cannot ascribe the actual wickedness or goodness fully to God either for God creates the potential, serves as a catalyst, but ultimately it is human hands that shape the events that unfold.

The idea of the miracle in Judaism then is far from a wholly supernatural occurrence, totally removed from human involvement. We come to appreciate through the Exodus narrative a kind of miraculous realism. A worldview that comprehends the role of God in this world but also appreciates the very present determining factor that we play in our own development. Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik in The Emergence of Ethical Man described it aptly when he wrote:

“What is a miracle in Judaism? The word ‘miracle’ in Hebrew does not possess the connotation of the supernatural. It has never been placed on transcendental level. ‘Miracle’ (pele,nes) describes only an outstanding event which causes amazement. A turning point in history is always a miracle, for it commands attention as an event which intervened fatefully in the formation of the group or that individual….Israel, however, who looked upon the universal occurrence as the continuous realization of a divine ethical will embedded into dead and living matter, could never classify the miracle as something unique and incomprehensible…Miracle is simply a natural event which causes historical metamorphosis. Whenever history is transfigured under the impact of cosmic dynamics, we encounter a miracle. (pgs. 185-186)“

Thus, the seder and our reliving the Exodus through evocative and symbolic ritual actions, becomes the impetus for our involvement in the betterment of this world. We come to understand that both are possible, the good and the bad, and that the potential for both was brought forth by God, but what happens with that potential, is in our hands to mold and shape.