If you’ve never heard the term dialectical materialism, you’re far from alone.

Dialectical materialism, or “diamat,” is a worldview and philosophy created by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It is one of the most important aspects of Marxism, and encapsulates all of Marx’s ideas about the world, society, economics, and what he thought was the immanent socialist revolution.

But, perhaps surprisingly, it is often an obscure, opaque topic. Many Marxists don’t even understand it, or don’t understand it well enough to explain it to someone else. It took me months before I had a firm grasp on it, and to my dismay, there are very few online resources that put it in concise, understandable terms.

Let’s start to rectify that. Here is a primer on dialectical materialism, from someone who believes in it, put in terms anyone should be able to understand. Obviously I’ll be streamlining and simplifying, but this is a basic overview of what it means and why it’s important. It will serve as an introduction to a future post, where I will explore the implications of dialectical materialism for Christianity.

Dialectical Materialism is a way of understanding society, history, and the world around us. Applied properly, it can explain just about everything there is to do with humans, our civilizations, our cultures, our religion, etc.

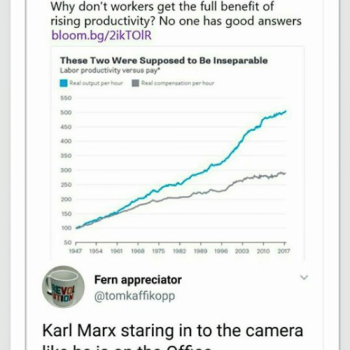

Basically, the type of society we live in is dependent on the “mode of production” in which we live. As Engels put it: “The determining factor in history is, in the final instance, the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life.” This includes the propagation of the species.

Human society is based on the production of food, clothing, shelter, tools, resources, etc. Without these things, we would never have been able to expand and flourish. The natural resources we have available to us, plus our ability to shape these resources to our liking, plus the relations between individuals, groups, and classes, form what is called the base of a society.

Materialism in this sense means that the world (and human society) is made up of material things, or, put more scientifically, of matter. This was Marx’s alternative to GWF Hegel’s “idealism,” which basically holds that things are the way they are because of our ideas. Idealism holds that there is no “objective reality” and that reality is in some way dependent on the human mind. It is the basis of postmodernism and wholly rejected by most Marxists, although Marx greatly admired Hegel (and Hegel’s philosophy is much more complicated than we have time to get into).

To illustrate the differences between materialism and idealism in practice, let us consider two explanations for the fact that European empires dominated indigenous peoples on every continent for over half a millennium.

The (not necessarily Hegelian) idealist might posit that Europeans were able to colonize the rest of the world because Europeans are somehow inherently superior, or ordained by God to do so – that is a form of idealism as it is based on “ideas” about the world, and about people. The materialist explanation for European imperial/colonial domination is that European cultures, due to their close proximity to each other which facilitated trade, exchange, and competition, reached higher levels of technological achievement than most other parts of the world, which they then leveraged into military domination. One is based on ideas, the other on material conditions. Which makes more sense to you?

So we understand materialism, but what makes it “dialectical”? Dialectics means two or more things are constantly affecting each other, back and forth, back and forth, until they reach a culmination of some sort. In idealism, this culmination is the synthesis of a thesis and antithesis. In materialism, this culmination is revolution.

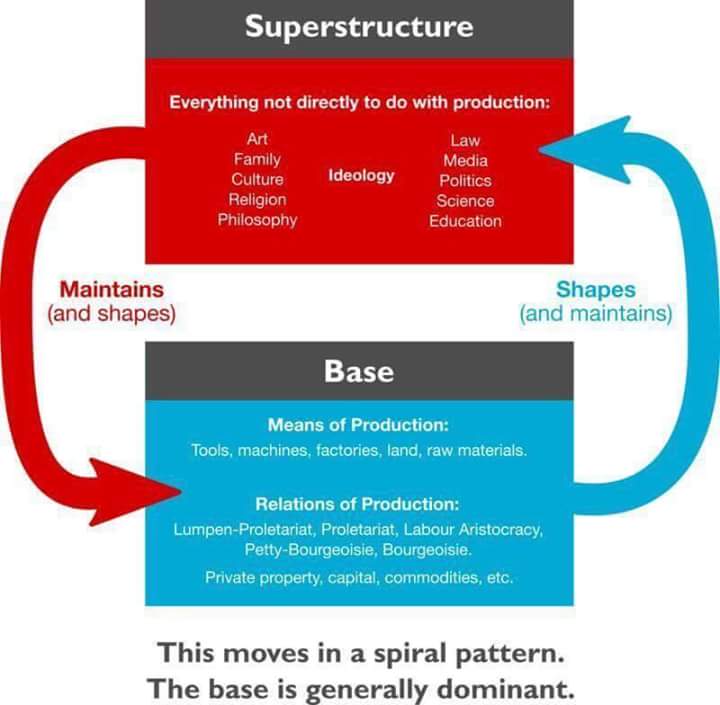

Remember our base, which encapsulates the material realities of the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life. It is only one half of our dialectic; the second half is called the superstructure.

The superstructure is all of the elements of society not directly related to production. These elements are apparent to even the least astute observer. It’s the art a society creates, its family values, its religious makeup, its societal norms, its politics, and on and on.

All of that stuff doesn’t seem like it has anything to do with the “production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life,” but it really does. For example, in prehistoric or “stone age” human societies with no concept of private property, monogamy was much less common (or even non-existent) and marriage did not exist. But when these societies evolve to horticultural and agricultural societies with tools and implements (means of production) capable of creating a surplus, the concept of “private property” arises, and with it marriage and the family, which is the only way to ensure that a man’s property is truly left to HIS children when he dies (parentage was matrilineal in human societies before the development of private property). Thus you get patriarchy, slut-shaming, and gender roles.

So the base creates the superstructure, which then reinforces the base. Think of orthodox Christianity’s emphasis on “obeying your Earthly masters,” working hard, and achieving a heavenly afterlife at the expense of a decent life on Earth. This pacifies people on the lowest rungs of society by encouraging them to accept the relations of production, or the base. The base forms the superstructure, which reinforces the base.

But that is not the whole story. The base shapes (and maintains) the superstructure, which maintains (and shapes) the base. But there is still the culmination of this process: revolution.

Revolution occurs when internal contradictions within a society’s base create what I’ll call “dissenting forces” within the superstructure. When these dissenting forces reach critical mass, they will destroy the old base and replace it with a new one. Slavery became feudalism, feudalism became capitalism, capitalism will become socialism.

This is why social movements and ideologies that challenge the base are often crushed by the dominant powers of the superstructure, most often the State. Think of revolutionary Christianity and the hippie movement, or Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter. These are movements within the superstructure that sought to fundamentally change the base. In the former two examples, the movements were neutered and gradually accepted into the superstructure in less revolutionary forms; the latter two examples were/are suppressed, often violently.

So, to sum up, the material conditions of a society (base) create the identity of that society (superstructure). The society continues until its internal contradictions create the material conditions for a revolution, which has the power to fundamentally restructure the base.

That, in a nutshell, is dialectical materialism. It is a simplified and overly linear explanation, but it is enough of an introduction to begin thinking dialectically. When I return I will flesh it out even more by going into detail with one example; I shall explore Christianity through the lens of dialectical materialism.

If you have any questions about me, Marxism, communism, Christianity, or anything else, leave them in the comments or drop me a line on Sarahah.