Or at least irrelevance. I note that in major cities across the United States, certainly mine, religious leaders are not longer a first call from either the local press or local politicians. Unless of course they make themselves news in ways that embarrass their fellow Christians.

Which isn’t news since Hauerwas and Willimon wrote Resident Aliens 26 years ago but which still hasn’t been taken on board by most Christians or their leaders. So I’ll state it:

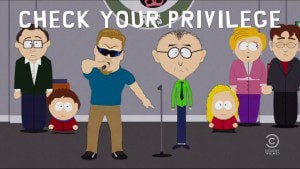

We do not live in the Christian world. Nor do we live in a Christian nation. The privilege accorded to Christians as a majority in the West and by the possession of colonizing power in the rest of the world is rapidly ending. And this means that our assumptions about the ways in which we relate to the world around us must change.

The position of our religious claims in the larger field of truth claims, insecure since the Enlightenment but carried forward by the inherit conservatism of culture, is now rapidly diminishing. If we simply assert the Bible as a source of truth we not only make a claim most humans do not accept, we make it within a form of discourse on authority that is as incomprehensible to most Americans as it would be if we spoke Tibetan.

Moreover the Christian values that underlie our ethical claims are no longer commonly accepted, so engaging public discourse about enacting ethics into law from a distinctly Christian perspective becomes harder and harder. And the rather obvious result is we are increasingly marginalized in realm of public policy. It has been decades since the assertion of a “moral majority” proved a political failure in affecting public policy. Despite short term gains by highly motivated Christian minorities in the realm of reproductive rights, the trend of public opinion is in the direction of understanding human life through the lens of a popular culture influenced by science and vague ideas about spirituality rather than any particular religious teaching.

When people want to know what it means to be human they are more likely to consult a doctor, nutritionist or personal trainer than a pastor or even a Christian friend.

Even as this happens our megachurches both deceive us and stand as a proof of our waning potency in the realm of public truth and policy. They are deceptive because they appear to be large and powerful. Yet they have achieved their size largely by cannibalizing smaller churches and doing so in places where population growth provides a ready source of new members. Nowhere is the growth of Christian churches keeping pace with population growth, and everywhere their decline is faster than population decline.

As a result many mega-churches are cultural ghettos where every week a fantasy America is ritually re-enacted while having no more discernible effect on the real America than the sporting events that make up the second half of our national fantasy day. Yes big churches do big good things, but actually effecting political and social change does not appear to be one of them.

If we are to remain relevant both to public discourse about the future of our society and individual lives seeking meaning we must engage in dialogue and apologetics. I will take up the first of these in this post.

Thus far conservative Christians have counted on their direct relations with politicians and particularly the Republican party to influence public policy. Yet it is relatively easy to see that while this sometimes pays off at a state or local level, arenas in which a highly mobilized minority can swing an election, it has yet to pay off at a national level, at least with regard to those key ethical issues that animate conservative Christians.

One reason is that conservative Christians have failed to engage in dialogue with non-Christians who share many of their values. In particular conservative Christian attacks on non-Christian religions such as Islam and Hinduism have alienated communities that largely share their non-modern worldview and values.

Most progressive Christians, while theoretically committed to inter-religious dialogue, have in fact shown little interest in actually engaging non-Christians in discussions touching on basic values and their implications for public policy. Progressives appear to assume that all religions are based on common values and lead to a common progressive destiny so there is no need for dialogue prior to advocating policies.

(To those deeply involved in dialogue, such as myself, this will appear a strange assertion. But look at the facts: even in cities like Houston, Chicago, and New York that have ongoing professionally run centers for dialogue inter-religious dialogue engages an immeasurably small part of the Christian population. More importantly, in my own context I have yet to see a serious inter-religious discussion about what separates progressive Christians from most non-Christians: the question of what constitutes a human person in the matrix of Divine law.)

Yet most consequential for the waning Christian voice in the public square has been the waning interest of Christians to engage in a dialogue with non-religious groups; social scientists, physical scientists, political scientists, educationalists, journalists, NGO’s, political activists and others that are far more influential in shaping policy than any religious group.

This was not always the case. Just 40 or 50 years ago the leading edge of theology was its engagement with the sciences and the critical observation that to remain relevant Christian ethical claims had to find their way within modern understandings of the human person and society or deny modernity altogether in order to pose a robust alternative.

Today conservative Christians remain antagonistic toward science in general, and have taken hard line ideological stances with regard to issues such as climate change, reproductive rights, gun control, and refugees rather than engaging social and political scientists in dialogue. They continue to insist on hegemony when they no longer have the votes.

Progressive Christians are more open to dialogue, particularly with regard to climate change and theologies of ecology. And this certainly has positive implications for public policy. Yet at a deeper level I wonder whether, apart from from corners of academia, they have really engaged scientists with their understanding of the human person in the larger context of reality. Central to this, and for a future blog, is the radical shift in imagined standpoint necessary to make sense of contemporary cosmological theories. It may be that the contemporary interest in meditation and meditative states, barely even considered by most Christians, results from a popular realization that comprehending both the self and the universe can no longer be achieved by commonsense observation and reason, and isn’t being seriously addressed by most Christian theologians.

To move from large scale analysis to political action will require engaging in dialogue with a wide range of scientists who map the intricacies of how the natural and social worlds actually work so that the thousands of minute steps forward necessary to achieve ideals such as social justice can be mapped out. And then there must be dialogue with all forms of media to effectively propagate ideas through society. And finally dialogue with elected representatives (including those who are recalcitrant) to show them the only thing they understand – the political value to themselves of making these small changes.

Until that happens progressive Christians remain in many ways as ideologically hog-tied as conservative Christians.

(The university is the ideal place for this dialogue to happen, and at its best is the place that it does happen. However, there are many forces working against such dialogue in a university. More importantly, universities appear to be a declining force in shaping American discourse over values. Not merely theologians, but whole university faculties need to be engaged in public dialogue.)

I suspect that both conservative and progressive Christians share in common a particularly American religious failing: They are so committed to the rapid realization of an eschatological vision of God’s reign that they cannot strategize beyond a single election cycle and they cannot compromise with long-standing political realities.

And this is in many ways odd – because in my reading of scripture all the apocalyptic language is designed precisely to warn of the limited human possibilities for effecting rapid structural change. Only God’s dramatic intervention in human affairs will make possible the New Jerusalem. Believers who do not know the day or the hour must focus instead on the demands of personal faith and obedience (which in democracies involves citizen engagement in politics) that like salt and leaven gradually make the larger society both palatable and edible.

So dialogue, real dialogue rather than ideological sloganeering, is the key to recovering a Christian voice in contemporary society. And that must begin by bringing discourse about the reign of God from the realm of ideological demands to the realm of real-world political compromise.

Going further, I suspect that in public discourse we may need to abandon the language of God’s reign and communicate our ideas in terms that can be understood to a non-Christian and even non-religious public. Or more precisely, in dialogue we will need to work out with others the language that allows us to communicate our values effectively.

Finally, we will almost certainly need to develop, again in dialogue, a theological anthropology that makes sense in light of the experience of self by those with whom we wish to partner in achieving what we might provisionally call “human flourishing.” And we’ll need to do this in dialogue with, or at least attentive to, the script writers, movie directors, pop-rockers, bloggers, magazine editors, celebrities, sports stars and media moguls that are among the new shapers of America’s social self-understanding, as well as the language of its self-expression.

But that takes us to the second great task besides dialogue in which we must engage: apologetics. Because our formerly privileged place in society cannot be taken for granted, we must now show a skeptical society that our faith is both credible and has a positive role to play in emerging forms of human self-understanding.