What Has Happened to “Substitutionary Atonement” among American Evangelicals?

Yesterday (October 19, 2017) my ready-to-graduate seminary students and I had a vigorous discussion about the “atonement.” We had read Swiss theologian Emil Brunner’s chapter on “The Work of Christ” in volume 2 of his Dogmatics the title of which is The Christian Doctrine of Creation and Redemption (Wipf & Stock, 2016). In the chapter division that deals with Christ’s “office” of “priesthood” (the three offices being prophet, priest and king) Brunner, like his Swiss counterpart, strongly affirms “objective atonement”—that Christ’s death on the cross cannot be reduced to a “subjective moral example” or even a victory over Satan and the power and principalities that hold sinners captive. He affirms many New Testament images of Christ’s priestly work but argues that this one—Christ’s substitutionary atonement in our place is central to Christian belief about Christ’s saving work for us. (He rejects Anselm’s “satisfaction theory” but only because he interprets it as making Christ’s atoning death necessary—not only for our salvation but necessary for God. That criticism comes across a bit unclear and possibly even mistaken.)

In introduced this question and asked my students to muse about it (without giving them much time to think about it): Why is it that, during my lifetime, evangelical Christianity in America seems to have largely forgotten and possibly even discarded the theme of substitutionary atonement? By “substitutionary atonement” I explained that I mean the idea that we should have been crucified—separated from God as Jesus was (or felt he was) on the cross. That he took our place and suffered the punishment (separation from God) we deserve.

This doctrine was absolutely central to evangelicalism in America in the 1950s and before. I won’t say it was necessarily “orthodox” in sense that any other view was automatically heretical, but the vast majority of evangelical churches in the 1950s and before simply assumed it as part and parcel of the gospel. I have examined the Statements of Faith (doctrinal statements) of many American evangelical denominations and usually see there some reference to “substitutionary atonement.” (Many people have mistaken come to think of it as somehow intrinsically and uniquely Reformed; that is simply false. John Wesley strongly affirmed substitutionary atonement. Later Methodists largely turned toward what came to be called the Governmental Theory but, as I have argued here, that is also substitutionary. I’m not going to repeat that here; you can find it in this blog’s archives.)

*Sidebar: The opinions expressed here are my own (or those of the guest writer); I do not speak for any other person, group or organization; nor do I imply that the opinions expressed here reflect those of any other person, group or organization unless I say so specifically. Before commenting read the entire post and the “Note to commenters” at its end.*

So I asked my students why so many contemporary American evangelicals shy away from this language—in sermons, hymns, teaching, etc. For example, several hymnals used in evangelical churches have changed the words of hymns that originally implied substitutionary atonement to imply instead that Christ’s death on the cross was a moral example and influence.

I was blown away by how well, how masterfully, my students articulated the reasons for this change. I’m not sure all the reasons were articulated, but many were so convincingly.

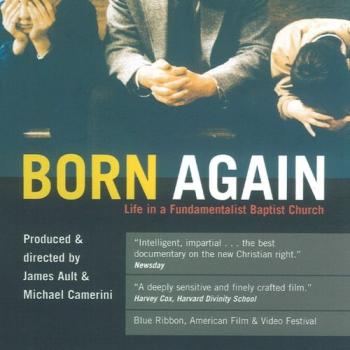

One African-American student, though, stated that in most black churches substitutionary atonement is still preached and sung and taught. He even went so far as to say that if a black preacher neglected it in a sermon about the cross he would probably be corrected by the “Church Mothers”—the influential and highly spiritual mostly older women of the church. They would tell him to go back up and finish his sermon (he said)! That rings true of the evangelical Christianity of my youth (1950s into the 1970s). But I find it difficult to find this emphasis on substitutionary atonement now—outside of black churches and white fundamentalist churches. So-called “moderate, mainstream evangelicalism” that is mostly white seems to have lessened this theme’s importance of not abandoned it altogether.

A few years ago Richard Mouw, who was still then president of Fuller Theological Seminary and a leading American evangelical theologian, wrote an article that was published in Christianity Today about “Why Christus Victor Is Not Enough.” He was picking up on the same change I’m talking about here, only I think many evangelicals don’t even know that language about the atonement and have adopted the Abelardian “moral example” theory. Mouw argued very cogently in that article that substitutionary atonement is central to the gospel.

My students articulated these reasons for the shift (which they agreed seems to have happened insofar as my story—which is not theirs because I’m much older—is true).

First, much preaching about substitutionary atonement strongly implies that God the Father is angry at us, hates us (as sinners), and wants to send us to hell, but that Jesus got in the way of God the Father’s wrath and saved us by becoming God the Father’s victim in our place. In other words, it creates problems for the Trinity and divides the Father and the Son in terms of their essential characters and dispositions.

Second, many people, including many contemporary Christians, don’t like to think of themselves as deserving what Jesus suffered. Generally speaking, contemporary people (at least in America) don’t believe we are all that bad or guilty enough to deserve such separation from God as Jesus experienced on the cross (to say nothing of the bloody torture he endured).

Third, the imagery of substitutionary atonement tends to include, if not dwell on, the bloody sacrifice of Jesus on the cross. It’s (in the inimitable words of Harry Emerson Fosdick) “slaughterhouse religion” that seems to many contemporary Americans, including many Christians, disgusting and revolting.

I wasn’t able to give all of my responses in that conversation, but here is what I would say to them.

First, much preaching and teaching of substitutionary atonement misrepresents it; it is rarely articulated by preachers “as it really is.” The motive for it is God’s love—including the Father’s love for us.

Second, I agree that many contemporary Americans, including many Christians, have lost a sense of their own sinfulness, guilt and alienation from God. And, for the most part, even evangelical preachers have gone along with that loss and done little re-awaken it.

Third, the imagery of blood and agony and torture is not crucial to the substitutionary view of the atonement; the “atonement” happened through Jesus’s abandonment by God the Father. (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”)

I tend to think that, over time, substitutionary atonement has become distorted and misrepresented. A question is: Is it too late to recover it? If so, I sometimes wonder if “contemporary American evangelical Christianity” is the same Christianity I grew up with.

*Note to commenters: This blog is not a discussion board; please respond with a question or comment only to me. If you do not share my evangelical Christian perspective (very broadly defined), feel free to ask a question for clarification, but know that this is not a space for debating incommensurate perspectives/worldviews. In any case, know that there is no guarantee that your question or comment will be posted by the moderator or answered by the writer. If you hope for your question or comment to appear here and be answered or responded to, make sure it is civil, respectful, and “on topic.” Do not comment if you have not read the entire post and do not misrepresent what it says. Keep any comment (including questions) to minimal length; do not post essays, sermons or testimonies here. Do not post links to internet sites here. This is a space for expressions of the blogger’s (or guest writers’) opinions and constructive dialogue among evangelical Christians (very broadly defined).