Maybe I missed out on a fundamental aspect of being a Cajun. Maybe my ancestors roll over in their graves when I admit this.

I’m not a big fan of Mardi Gras.

I can pretend it’s because of a noble reason – that the modern celebration of Mardi Gras has little to do with the authentic celebration of feasting before the long Lenten fast preceding Easter.

The truth though is that Mardi Gras brings out two of my worst enemies as an awkward introvert – large crowds and loud inebriation – all for an indecent amount of cheap plastic beads and watery American beer. Ever since I was born, I was brought to loud parades lined with tractors pulling colorful paper-mache floats amid swarms of spectators who shout and sometimes drunkenly bully one another to get the precious plastic beads thrown.

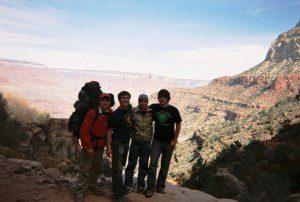

In 2009, when I was offered to get away from the Mardi Gras Mambo that weekend in my college town, I happily found myself on a roadtrip with three good friends from college, headed to the Grand Canyon.

We spent the first night in a tent on the top of the canyon. The next morning we woke up at sunrise to get an early start for the 6-mile hike down to the canyon bed and the Colorado River. We assumed (correctly) that the hike would take us all day. That wasn’t because we were out of shape, but because my friends were determined to take me to the bottom – wheelchair and all.

Our hike down the canyon had barely begun when we released our plan wasn’t going to work. We must have chosen the wrong trail, because even though we were told that the path was entirely wheelchair accessible, we realized within less of a tenth of the way down that pushing me in my wheelchair wasn’t feasible. Rather than backtracking and finding an easier trail, we decided to abandon my wheelchair at the nearest waystation (there was one every quarter of the way down the trail) and I would ride down on my friend Joseph’s back.

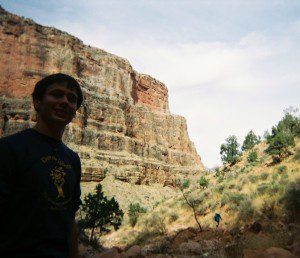

As we hiked down the trail, we were passed many times by people who paid to ride mules to the bottom of the canyon. In the first quarter of my descent, the mule-riders would pass my friends Ben and Jason, frustratingly trying to push my empty wheelchair with their packs and gear on it down the trail. (“Well, that’s one way to do it!” one of them heckled at my friends and chuckled as he passed.) When later down the trail the mule-riders encountered Joseph, with me instead of a backpack on his back, the situation clicked for them; a number of them cried at the situation as they passed us. But the real reason they should have cried is because they paid a lot of money to ride their mules, and I rode on the back of a jackass for free.

When we finally made it to the bottom, sans wheelchair, I was entirely reliant on my friends. Having my own worst nightmare come to pass in such an idyllic place seemed incongruent, yet losing most of my own independence, surrounded by the pleasant February chill and the lush green landscape surrounded by desert – an oasis beneath a crack in the ground – was strangely not terrible. Facing terrible situations like my own helplessness is never as awful as my foreboding makes it.

I probably should learn that by now. However, when a scary situation is before me, I tend to brood over it; I don’t quite run away from it out of fear, but I do prepare myself for the worst.

When I was 14 and found out I’d soon require a wheelchair from the progression of my disorder, Friedreich’s ataxia, the thought of being dependent in order to be ambulatory was devastating to me. Any perceived threat that caused a loss of independence horrified me.

After supporting my walking throughout high school by leaning on the walls of the hallway, I realized that that was not an option in college with classrooms spread across a sprawling campus. Seeing no other option, I finally succumbed and agreed to use a motorized wheelchair on campus.

A week before classes began, I took my motorized wheelchair to the university to try it out. Not only did riding in the wheelchair not make me feel ashamed or embarrassed as I’d feared, I felt empowered: for the first time in recent memory, I could move ahead of whoever was with me. I no longer felt that my situation was devastating.

That Lundi Gras, I stayed near our tent at the bottom of the Grand Canyon while my three friends hiked farther to see the Colorado River. I wrote in my journal, appreciating the still sounds of chirping insects, a quiet I wouldn’t know if I stayed at my apartment for Mardi Gras weekend.

“Strange,” I wrote, “how being entirely dependent on my friends who’ve brought me here doesn’t fill me with embarrassment. I’m discovering that life is vastly different than my expectations. Thank God for that.”

When my friends got back to the tent, we soon went to bed after sundown, knowing that tomorrow would be a whole lot tougher. Gravity, most times, is a bitch.

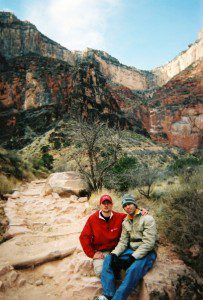

We awoke at sunrise, put our tent back in one of the three backpacks we’d taken with us. Joseph began carrying the large backpack, Ben carried the two smaller ones, and Jason carried me on his back. Every quarter mile or so, my three friends would rotate who carried what. Other hikers, who passed us along the way, offered to carry our bags for us. Eventually my friends had nothing to carry but a good-looking guy on their back. Hikers began stopping and sharing their food and water with us. We even were passed by a couple who offered to bring my wheelchair from the one-mile rest stop to the top for us.

As my friends got more and more tired and I was getting swapped more and more frequently, we began to get worried; it was past 4 pm, and we still had over a mile to go. Around this time, we passed a group of rangers who had just finished working on a part of the trail. They offered to help bring me to the top, but one ranger said, “We might not be able to do much; we’ve been working hard all day.”

I’d pay for you to see the dead-pan stare Ben gave that ranger after saying that.

So now I was being transferred between the four rangers’ backs. It became a competition among them, who could go the farthest and fastest with me.

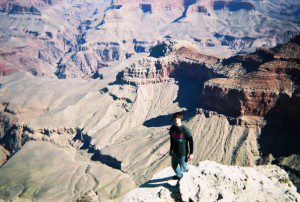

At about 6 pm, right before sunset, we made it to the top of the Grand Canyon. I teared up when I saw my trusty wheelchair and all of our equipment waiting for us.

We camped out again that night, woke up at dawn to watch the sunrise, then drove back to Louisiana.

That trip showed me the goodness within people. It’s not absolute, but especially in the dark and divisive present, it’s awesome for me to remember. I think of my friends, the fellow hikers, and the park rangers, who each gave some of their convenience to make my trip one I won’t forget.

Life is vastly different from my expectations.

Thank God for that.