Beginning in the 1980s, a feverish hysteria swept across America. It was centered in one demographic — the white evangelical subculture — but it wasn’t confined to that group, and it came to reshape the wider culture, the agenda of elected officials, and the political landscape of the country in fundamental ways, placing a fear of imaginary monsters at the core of our national identity.

That same moral panic continues to shape American culture today, decades after it first began making national headlines. It began in the 1980s, but it did not end there. It continues to wreak havoc on individual lives, and its reshaping of American politics has never been undone.

Nathanael Rich discusses a parallel hysteria in The New York Review of Books in an essay titled, “The Nightmare of the West Memphis Three.”

Nathanael Rich discusses a parallel hysteria in The New York Review of Books in an essay titled, “The Nightmare of the West Memphis Three.”

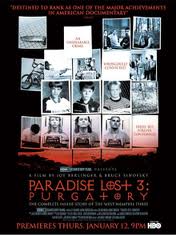

Rich is reviewing four documentaries on the infamous case of wrongful conviction, as well as the memoir written by Damien Echols — who was arrested at age 18 and sentenced to death for his role as the supposed ringleader of a “satanic cult” responsible for the murder of three young boys.

The “nightmare” fueled by fears of imaginary monsters resulted in three poor teenagers spending years in prison for a crime they did not commit. And it meant that whoever did kill those three children remains free — unpunished and unpursued. That’s what happens when we become obsessed with imaginary monsters: Real injustices go unaddressed even as new injustices are done to the innocent.

The existence of a satanic cult turned out to be wholly imaginary — not just in West Memphis, Ark., but anywhere. The central lie of the Satanic Panic is entirely fictional, entirely fabricated. But it persists because it is a lie that many people want to believe. People want to believe that our society is permeated by secret satanic cults practicing all manner of perverse and diabolical rituals. People want to believe that Satanists are out there killing babies.

If you’re not familiar with the story of the West Memphis Three, Rich’s essay provides a good introduction, summarizing the revelations from a series of documentaries produced for HBO Films:

Were it not for HBO Films, there would be no “West Memphis Three” — only three convicted murderers, two serving life sentences and one, most likely, executed. This is not a credit to HBOas much as it is an indictment of the American justice system and one of the founding assumptions on which it stands.

Paradise Lost’s directors, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, were not lured by a story of wrongful conviction; they went to West Memphis to make a film about Satanic bloodlust and sexual mutilation. The crime occurred at the end of a roughly five-year period, beginning in the late 1980s, in which fears of Satanic ritual abuse had become widespread in American popular culture. The scare extended even into law enforcement, to such an extent that the FBI commissioned a study on the subject in 1991. (The authors concluded that “after all the hype and hysteria is put aside, the realization sets in that most Satanic or occult activity involves the commission of no crimes, and that which does, usually involves the commission of relatively minor crimes such as trespassing, vandalism, cruelty to animals, or petty thievery.”)

Berlinger and Sinofsky spent their first several months in Arkansas interviewing the victims’ parents. The filmmakers began to question the premise of the suspects’ guilt only after they went on to interview the young men in prison. They realized then that they’d stumbled upon a story with even higher dramatic stakes — instead of a real-life Rosemary’s Baby, they had a modern-day Salem Witch Trials.

Rich’s chronology is off. He rightly sees that the West Memphis case can only be understood within the wider context of the Satanic Panic, but he shares the widely held, but incorrect, view that the panic was a brief, 1980s phenomena. He thus tries to compress the Satanic Panic into a “roughly five-year period” including the West Memphis case. But the West Memphis trial was in 1994 — more than a decade after the McMartin Preschool hysteria began and nearly a decade after the notorious 1985 20/20 “special report” on Satanism.

Rich’s compressed timeline doesn’t work. The Satanic Panic began in the early 1980s (the fraudulent “memoir” Michelle Remembers was published in 1980), and as the West Memphis case demonstrates, it was still influential well into the 1990s.

The foremost “expert” in that 1985 20/20 report is Mike Warnke — a comic-turned con-artist who made his fortune selling fraudulent stories of his lurid past as the high-priest of a Satanic “coven.” Warnke was exposed as a fraud by two reporters from Cornerstone magazine in 1992. Mike Hertenstein and Jon Trott published a book-length report on Warnke’s scam in July of 1993 — Selling Satan: The Evangelical Media and the Mike Warnke Scandal.

And yet the following year, a self-proclaimed “occult expert” named Dale Griffis was the prosecution’s star witness in convicting the three teenagers in West Memphis. Griffis was also featured in that 20/20 report, and he cites Warnke as a scholarly authority in his “research.” Nearly all such “expert witnesses” still do — even now, 20 years after Hertenstein and Trott’s book exposed Warnke’s expertise as nothing but lies.

I’ve only seen one of the Paradise Lost documentaries — the third one, produced after the West Memphis Three were released from prison in a begrudging Alford plea deal. It is by turns heart-breaking and infuriating — a picture of just one case that shows how much real damage is done by the obsessive battle against imaginary monsters.

Beginning in the 1980s, a feverish hysteria swept across America. It was centered in one demographic — the white evangelical subculture — but it wasn’t confined to that group, and it came to reshape the wider culture, the agenda of elected officials, and the political landscape of the country in fundamental ways, placing a fear of imaginary monsters at the core of our national identity.

Maybe it’s just a coincidence that the Satanic Panic began at the same time, and within the same demographic, and with the same emotional fervor in pursuit of the same emotional rewards. But the two things are too similar for me to accept such an extraordinary coincidence.