Look, I get it. Gestures are no substitute for substantial action, and otherwise positive-seeming gestures may become harmful when people treat them as though they are. I agree.

Someone’s got a T-shirt that says “Work for Justice”? Cool. That’s a Good Thing. But it could become a Bad Thing if that person starts to think that buying and wearing that T-shirt is all they need to do to work for justice. Valid point.

But I don’t think the best way to make that point is by scolding anyone you see wearing such a T-shirt.

Which is why many of the people using the terms “slacktivism” and “slacktivist” probably shouldn’t be. I’m not just being proprietary here — this non-ironic, pejorative use of those words doesn’t work. It’s self-defeating. It repositions the speaker as a scold. And as a particular kind of scold — the ineffective, irrelevant grumpy old person whining about how kids these days are no damn good.

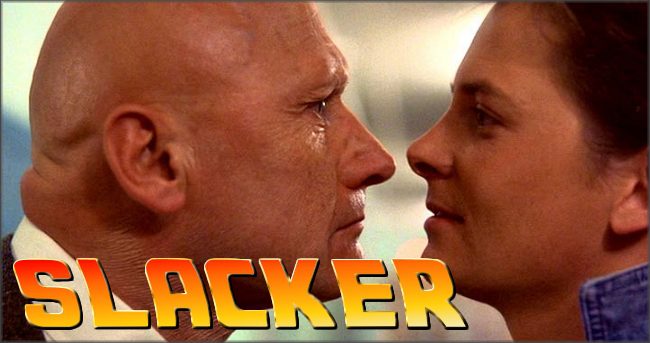

To use these words unironically as a condemnation of “slacktivism” is to accept the mantle of Vice Principal Strickland:

That’s him there, on the left, chewing out Marty McFly for being a “slacker.”

The important thing to remember about Vice Principal Strickland is that he was wrong. He was specifically wrong in dismissing Marty. And he was archetypally wrong on behalf of all grumpy old people everywhere for dismissing all young people everywhere as “slackers.”

To embrace the vocabulary of Strickland is to embrace the role of Strickland and the essential wrongness of Strickland. And that shifts the meaning of all these critiques of so-called “slacktivism.” The intended lecture on the need for substantial action beyond hollow gestures is translated into a very different lecture — one that criticizes kids these days because they’re not taking the same exact actions that we took when we were their age. (Or even, perhaps, criticizing kidsthesedays for not making the same exact hollow gestures that we made when we were their age.)

Take, for example, Evgeny Morozov’s “The brave new world of slacktivism,” in Foreign Policy. That’s from 2009, but it’s still frequently cited as some kind of seminal work on the topic. “Slacktivism is the ideal type of activism for a lazy generation,” Morozov begins, and thus concludes beforehand. He might as well have put on a bald wig and a bow tie, because he’s going full-Strickland.

Morozov’s pairing of “slacktivism” with “lazy generation” is redundant, but he’s not just repeating himself — he’s repeating centuries of equally banal “this new generation is lazy” lectures recited by every generation of old people disappointed to realize that younger people might not be able to fix all of the mistakes and injustices bequeathed to them by the aforementioned generation of old people. All you lazy kids tweetering on your FaceSpace need to just get off my lawn!

If it’s not being used ironically, then the term “slacktivism” is a one-word synonym for all such lectures. Using that word in earnest as a pejorative puts one half a step away from the Four Yorkshiremen sketch. (“Aye, you try and tell that to the young people of today. …”)

Morozov’s follow-up, “From slacktivism to activism,” is constructive in a way his earlier scolding is not, but it’s still muddled by his choice to employ that intrinsically dismissive and generational term “slacker.” Morozov argues, rightly, that “At some point one simply needs to learn how to convert awareness into action,” and that too many online campaigns “do not have clear goals or agenda items beyond awareness-raising.”

Excellent point! And his suggestions for how to address this problem seem smart and insightful:

Make it hard for your supporters to become a slacktivist: don’t give people their identity trophies until they have proved their worth. The merit badge should come as a result of their successful and effective contributions to your campaign rather than precede it. … Create diverse, distinctive, and non-trivial tasks; your supporters can do more than just click “send to all” button” all day. Since most digital activism campaigns are bound to suffer from the problem of diffusion of responsibility, make it impossible for your supporters to fade into the crowd and “free ride” on the work of other people.

But he can’t let go of that pejorative use of “slacktivist” and you can see how his unironic embrace of it Strickland-izes his view of others. The slackers of this lazy generation can’t be expected to contribute in any meaningful way for any meaningful reason. They’re not interested in changing the world like we were when we were their age — they’re only motivated by “identity trophies” and “merit badges.” (Yeah, that bit. It’d be nice, just once, to hear someone born before the Moon landing discuss the Millennial generation without sneering about “trophies,” but I suppose that clichés, like hairstyles, ossify with age.)

I’m afraid the rest of Morozov’s paper hasn’t aged very well. “I’ve grown increasingly skeptical of numerous digital activism campaigns that attempt to change the world through Facebook and Twitter,” he wrote, in Foreign Policy, in 2009, and mentioning Egyptian and Tunisian online campaigns as examples confirming that skepticism. Zine el Abidine Ben Ali probably wishes he’d been right about that.

Yet, aside from the sneering at “slackers,” Morozov’s insight there about engaging people by asking them to make substantial contributions before receiving any kind of public affirmation still seems sound. And it’s recently been sort-of confirmed by a fascinating bit of research.

Kirk Kristofferson, Katherine White and John Peloza set out to explore “How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action.” Unfortunately, however, they chose to publish the results of this exploration in a paper titled, “The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action” (.pdf from the Journal of Consumer Research, Sept. 11, 2013).

Science Daily summarizes their findings:

The study results add fuel to recent assertions that social media platforms are turning people into “slacktivists” by making it easy for them to associate with a cause without committing resources to support it.

In a series of studies, researchers invited participants to engage in an initial act of free support for a cause — joining a Facebook group, accepting a poppy, pin or magnet, or signing a petition. Participants were then asked to donate money or volunteer.

They found that the more public the token show of endorsement, the less likely participants are to provide meaningful support later. If participants were provided with the chance to express token support more privately, such as confidentially signing a petition, they were more likely to give later.

The researchers suggest this occurs because giving public endorsement satisfies the desire to look good to others, reducing the urgency to give later. Providing token support in private leads people to perceive their values are aligned with the cause without the payoff of having people witness it.

As I said, this is fascinating. It’s probably also provides some useful advice, even if I’m not yet wholly convinced that it means what the researchers think.

Some participants, for example, may accept the initial “token show of endorsement” and perceive this as evidence that this group isn’t doing much more than just handing out such tokens and is not itself capable of more substantial “prosocial action.” When later asked to donate money or to stuff envelopes on behalf of the group, those participants may then decline — not because they’ve already received their public affirmation, but because the initial gesture left them unimpressed with this particular group.

The study, in other words, presumes and asserts the worthiness and effectiveness of the hypothetical group endorsing the cause in the study, but participants have no reason to share this presumption or to accept this assertion — and the experiment itself suggests one reason not to.

At the same time, participants in the study are presumed to be slackers until they demonstrate otherwise — but they only way the study recognizes for them to do so is according to the terms of the study itself. Anyone who fails to conform to that form of “prosocial action” is presumed to be not engaged in prosocial action — a slacker and “slacktivist,” rather than a legitimate activist.

And yet again we come to that inescapable generational aspect lurking in every criticism of “slackers” and every non-ironic condemnation of those young slackers’ “slacktivism.” When the most meaningful or substantial invitation to a young person is a request for a financial donation, that young person will often have two thoughts: 1) “I haven’t got much money;” and 2) “This outfit doesn’t have much use for people like me, so I’ll smile and nod, exchange token gestures with them, and then keep looking for a group that needs the kind of contribution I am able to provide.” And when the most meaningful invitation involves stuffing envelopes, a younger person may think “Really? In 2013 people are still doing direct mail?”

If we define “prosocial action” as a specific set of acts and forms, frozen in time, unchanging and inalterable since the 1960s, then we’ve already predetermined that future generations will fail our little test for them. They’re not going to do exactly what we did in exactly the same way we did it.

If we expect them to, then all we’ll ever see when we look at them is a bunch of slackers. And no matter what those slackers do, or why, we’ll have already dismissed it as a “costless, token display.”