Memorial Day is one time during the year when American civil religion imitates one of my least favorite aspects of the white evangelical Christianity that I was raised in. It takes the kernel of an idea of something right and honorable and spins it into a defensive, sanctimonious, performative ritual — one which makes sincerity and truth-telling almost impossible.

It is a time, in other words, when we say that which we are expected to say, even if — and perhaps especially if — we know it is not true. We say what we are expected and directed and required to say because we are being watched and monitored and evaluated for our willingness to say it. The point is not about saying what we believe to be true, but rather about affirming our membership in the tribe of people who recite such affirmations. This recitation is not optional. Those who fail to make it with the appropriate simulacrum of sincerity will be sanctioned.

“Can we tell the truth on Memorial Day?” Craig M. Watts asks at Red Letter Christians. And the answer, I think, is No — not if we know what’s good for us.

“I have told the whole truth in that,” Mark Twain said, “and only dead men can tell the truth in this world. It can be published after I am dead.” He was speaking of “The War Prayer” — a harshly satiric fable in which Twain wrote some of the truth that American civil religion forbids us to acknowledge on Memorial Day.

Watts is more hopeful than Twain. He believes that truth-telling is possible, if difficult. “While some truth is given voice on this solemn occasion, there are other important truths that are distorted in the telling or pushed from memory altogether,” Watts writes:

Too often on Memorial Day, rather than remembering individuals who tragically died in battle, an idealized version of the war dead is presented. The dead are indiscriminately described as “heroes.” Sweeping claims are made about the reason for their deaths: they died to “protect our freedom.” And in particular in churches we are told they died for the freedom of religion, the freedom to worship.

We are told soldiers “sacrificed themselves,” though they were actually sacrificed by politicians who sent them to war. And in churches scriptures are quoted to leave the impression they died as martyrs for their faith: “those who lose their life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 16:25).

Watts proposes three questions for Memorial Day, all of which are good questions. Here, though, let’s just focus on the first one:

(1) Can we remember without attributing reasons for war that aren’t in fact the real reasons? To celebrate Memorial Day by claiming soldiers died that we might be free is misleading. The real causes behind most wars have had little to do with protecting freedom of speech or assembly or worship. … Can we remember in a way that doesn’t falsify the causes of war, justify national self-righteousness, or turn Memorial Day into a recruiting tool to entice the young to enter the armed forces?

I understand that this ritual assertion of a falsehood — the war dead “died that we might be free” — is intended in part to ascribe the greatest possible honor to those who gave the last full measure of devotion. But if we owe them our gratitude, then we also owe them our honesty. The pretense that all wars, or even most wars, are fought to defend our freedom does not so much honor our war dead as it does guarantee that we’ll keep making more of them.

As Watts notes, the honor and gratitude at the heart of Memorial Day are appropriate. “Those Americans who suffered and died in war ought to be remembered,” he writes. We have a duty and an obligation to remember them and to honor their memory:

The grave difficulties endured by of those who faced armed conflict and lost their lives should be recognized. The soldiers’ best intentions in allowing themselves to be put in harm’s way – regardless of the actual reasons for war — deserve to be honored. But in the process, war itself should not be honored, the reasons for war whitewashed, nor should the suffering and the deaths of others be ignored.

And the whitewashing of the reasons for war starts, I think, with this ritual incantation of the false claim that war is perpetually necessary if we are to remain free.

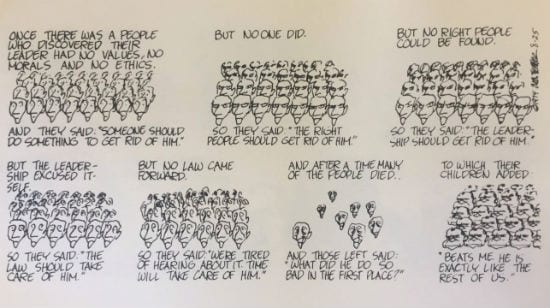

That is not true in the particulars nor is it true in the abstract and in general. Richard III did not say, “First, kill all the soldiers.” No tyrant has ever said such a thing. Tyrants like Richard need soldiers. They need someone to carry out that order, “First, kill all the lawyers” Or all the journalists, the prophets, the educators, the demonstrators. Nowadays, many tyrants and would-be tyrants seem to be saying “First, kill all the school girls.”

The cultic ritual glorification of war is not necessary to defend freedom. It may well be necessary, though, for getting rid of it. It is, at least, immensely useful for that purpose.

Here in America, Memorial Day began after the Civil War as a way of remembering and honoring those who died in that conflict. It was, and still is, a pale shadow of the true memorial that honors those more than 600,000 dead — the 13th Amendment, 14th Amendment and 15th Amendment. America has been at war for most of my lifetime and most of those wars have done more to undermine those laws than they have to defend them.

I’ll tell you what Memorial Day is all about, Charlie Brown. Lights please:

No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.