“O God, we pray …” the preacher says, and the words declaring the act are, at the same time, the act itself.

That’s odd, grammatically. Most verbs don’t work that way. If I say, “I swim,” I am not, thereby, committing the act of swimming. Describing swimming and actually swimming are two different things. Swimming and talking about swimming are not at all the same.

Yet when it comes to prayer, these two things merge together. “Let us pray,” the preacher says, describing what we are about to do. And then, “O God, we pray …” she says, and suddenly we are doing it.

“Pray” isn’t the only verb that works this way. “I thank you” is another example. The deed itself consists of reciting the same words we use to describe it. The giving of thanks involves the saying of “thanks.” I say, “I thank you,” and thereby I thank you.

Such thanksgiving or thanks-saying is, of course, part of what we do when we pray our prayers. And it turns out that most of the sorts of things we “do” when praying involve verbs that work this way. “We pray.” “We thank you.” “We request.” “We praise.”

Such thanksgiving or thanks-saying is, of course, part of what we do when we pray our prayers. And it turns out that most of the sorts of things we “do” when praying involve verbs that work this way. “We pray.” “We thank you.” “We request.” “We praise.”

That last one reminds us of another set of self-executing verbal verbs that work this way. “I praise you” is another example, but so are many of the words that convey the opposite of praise. I condemn. I rebuke. I challenge. We don’t usually think of these as the sorts of things one ought to do while praying, but a survey of biblical prayers shows these should be included in that category as well.

Verbs that work this way all share another odd feature in that, unlike most other verbs, they’re often entangled with the question of sincerity. When we watch someone swimming laps in a pool, we do not wonder if they are “really” swimming rather than just making hollow gestures that propel them back and forth across the water. The act is physical — the physical reality of it is apparent and so its authenticity, sincerity or genuineness is never in question. But those questions can linger after someone says “I thank” or “I condemn” or “I pray.”

What more are we looking for? The words have been spoken and the deed has been performed. The deed was performed through the speaking of the words. And yet there remains room for doubt. We may seek further confirmation that the person who said “I thank you” was really thanking us. But what does that mean? What more do we want?

Saying thanks is an expression of gratitude, but that just seems like another intangible, immeasurable thing. It’s an odd thing, gratitude. We’re expected to have it, to give all of it — without holding anything back — to those to whom we are grateful, and yet to still retain our full share of it after doing so. Trying to confirm the sincerity of thanks based on the sincerity of gratitude doesn’t seem to solve our problem — it just adds another layer of abstraction.

I think John the Baptist is helpful here. John didn’t call on his listeners to “repent,” but to “Bear fruits worthy of repentance.” Like any good teacher of Writing 101 his message was this: Show, don’t tell.

I think maybe all of these self-executing verbs require that. We thank by saying “thanks,” but it only becomes meaningful if we then bear fruits worthy of gratitude. We condemn by saying “we condemn,” but it only becomes meaningful if we then bear fruits worthy of condemnation. And so on.

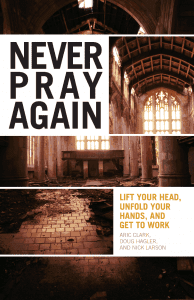

All of which is to say that I’m looking forward to reading the recent book from the good folks at Two Friars and a Fool, Never Pray Again: Lift Your Head, Unfold Your Hands, and Get to Work.