Last week we discussed “Club Amnesia” — the spring break frat party run by a nominal “church” called the Life Center in Panama City, Florida. Local officials have challenged the tax-exempt status of the church, deciding “That isn’t a church” at all, just a night club disingenuously claiming to be a church to take advantage of the tax and zoning laws for religious non-profits.

The officials can certainly point to some compelling evidence for that conclusion. There’s Club Amnesia’s “pajama and lingerie” parties advertising “the sexiest ladies on the beach.” The club charges a $20 cover and sells T-shirts with slogans like “I hate being sober.” They have naked body-painting and “Wet and Wild” nights with, the church says, “a little twerkin.” Plus the whole thing is run by a guy named Markus Bishop who has a rap-sheet for assault and sexual harassment.

But for all of that, Bishop says he’s a pastor. He says he’s a sincere religious believer running a legitimate ministry. The outlandish details of that ministry aren’t all that different from the “prosperity gospel” Bishop preached at his earlier church, a place called Faith Christian Family Church. When he was trying to reach a flock of financially insecure working-class people, Bishop preached a gospel of wealth. Now he’s trying to reach lonely college students with a gospel of beach parties, so how is that different? Why should the latter be a less legitimate form of “religion”?

Here’s the problem: The First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion requires that our laws do not burden or restrict that free exercise. And that means we will often need to carve out religious exemptions to specific laws or regulations.

Here’s the problem: The First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion requires that our laws do not burden or restrict that free exercise. And that means we will often need to carve out religious exemptions to specific laws or regulations.

Consider, for example, the military draft. Quakers have been a part of the fabric of American life since the earliest Colonial days. While the Friends aren’t a dogmatic bunch, pacifism has traditionally been a central, essential component of their religious faith. We can’t very well conscript Quakers to take up arms to defend the Constitution if forcing them to do so violates the very free exercise of religion that Constitution claims to guarantee.

So, OK then, we’ll carve out a religious exemption to the draft. Quakers and Mennonites and such — the traditional “peace churches” — will be granted an exemption in recognition of their religious liberty. We’ll allow for some alternate form of national service for those pacifist believers. So far so good.

But if religious liberty and the freedom of conscience is to mean anything, then it has to apply to everyone equally. And adherents of the traditional peace churches aren’t the only religious believers whose beliefs forbid them to take up arms. We’ve also got Dorothy Day Catholics and MLK Baptists and an assortment of other people whose religious convictions forbid them from participating in lethal violence. Their religious convictions may not be a formal aspect of the dogma of their respective sects, but they are still religious convictions. Forcing them to violate those convictions would violate their right to the free exercise of their religion. So what about them? What about their rights and their freedom of conscience?

OK, fine. We’ll expand the religious exemption to the draft to also include other religious believers who would be forced to violate their religious beliefs.

But we’re still not done yet. The First Amendment guarantee of the free exercise of religion also has to guarantee the right not to exercise religion. If it is to mean anything, then it must protect the right not to believe just as surely as the right to believe. And we’ve also got a bunch of Americans whose non-sectarian personal convictions forbid them from participating in lethal violence. These are core beliefs, and requiring them to violate those beliefs would mean denying them the freedom of conscience guaranteed by the First Amendment. What about them? What about their rights?

Eventually we figured that out too. It took a while, but our conscientious objector laws now protect the freedom of conscience of non-believers just as much as of believers (on paper, at least).

This same pattern can be seen in a host of different laws and exemptions written to protect Americans’ right to freedom of conscience as guaranteed by the First Amendment. Our courts have always been willing to take a hard look at our laws and to evaluate the application of those laws in the light of that First Amendment guarantee of religious liberty.

This has involved lots of thoughtful attempts to create a principled legal approach to evaluating such laws and their application. Our courts have used things like the so-called “Lemon Test,” named after a landmark 1971 religious liberty case. That test offers three principles for evaluating laws that involve freedom of conscience and the free exercise of religion:

- The law shouldn’t involve “excessive government entanglement” in religion;

- The law should neither advance nor inhibit religious practice; and

- The law needs to have some generally applicable non-sectarian purpose.

My point here isn’t to discuss whether or not the Lemon Test is adequate or whether it has been or should be consistently applied. I’m just noting it as an example of the courts’ attempt to create a principled, methodical approach to the necessary task of evaluating laws and their application in a way that honors the First Amendment guarantee of religious liberty.

On that half of the equation, the courts have made a clear effort. But that’s only one half of the equation.

And the bigger problem is that our courts are terrified of the other half of the equation. They’re willing to evaluate the legitimacy of our laws, but they’re utterly reluctant to apply the same principled legal consideration to evaluating the legitimacy of religious claims. And the validity of those religious exemptions is dependent on the validity of the religious claims being legally protected.

Again, it is understandable and even, at some level, commendable that our courts don’t want to get involved in making judgments about religious sincerity. Judges shouldn’t want to be put in the position of ruling on the legitimacy or sincerity of any individual’s religious or a-religious claims.

But tough luck. Making judgments is what judges do. And making judgments about the validity of religious claims is still an inescapable, unavoidable, necessary part of their job. By refusing to acknowledge or accept that part of their job, the courts are routinely screwing over local officials who don’t have the option of retreating to some lofty, abstract, above-the-fray perch. Those local officials are required — by laws upheld by the courts — to render judgments about the legitimacy and sincerity of religious claims. And that’s true whether or not the courts ever deign to provide them any guidance for doing so.

Florida law says that church property is tax exempt. Markus Q. Bishop says his wet-and-wild nightclub is a church and that therefore he doesn’t have to pay taxes on the property. Local officials in Panama City have no choice but to make a choice. They have to make a legal determination as to whether or not Bishop’s “church” is, legally and legitimately, a church. And they have to do so despite a Supreme Court that has — in recent rulings from Hosanna-Tabor to Hobby Lobby — extravagantly refused to offer any principled guidance for that determination.

Local officials all over the country face similar dilemmas every day. New Jersey’s Assembly is, right now, considering a bill to refine that state’s religious exemptions for child vaccination. Kids have to be vaccinated to attend public schools in the state. That’s a Good Thing, because epidemics of measles or whooping cough aren’t really conducive to education. Parents whose religious beliefs (or non-sectarian convictions of conscience) prohibit vaccination are granted an exemption from the requirement. That’s a Good Thing, too, because even though anti-vaxxers may be factually challenged ignoramuses, the First Amendment has to guarantee their right to be factually challenged ignoramuses if that nonsense is, for them, a sincerely held conviction of conscience.

But the “religious exemption” in New Jersey has been growing faster than anti-vaxxer ideology. It’s so easy to claim this exemption that parents who may have simply forgot to make an appointment, or failed to bother to do so, can just check the religious exemption box and get their kids enrolled anyway. The law, in other words, created a loophole that is being exploited by people with no legitimate or sincere claim of conscience.

Every such First Amendment exemption is vulnerable to such abuse and exploitation. And every local official charged with administering such exemptions is therefore forced to evaluate the legitimacy and sincerity of the religious/conscience claims being presented. Draft boards routinely have to evaluate the purported convictions of would-be conscientious objectors. Tax and zoning officials are constantly forced to consider whether or not a given purported “church” legitimately meets the legal definition of such a thing. Some poor soul who works at the DMV taking driver’s license photos says “Next” and a guy claiming to be a High Priest of the Church of Groucho sits down wearing a fake nose and mustache. Now what?

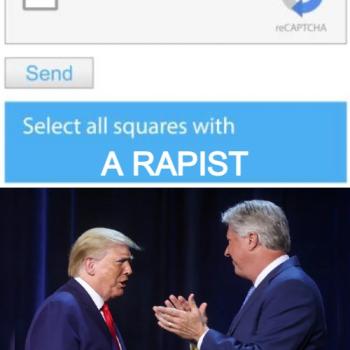

The Supreme Court is no help for these local officials. Their recent rulings have been so averse to any evaluation of the sincerity or legitimacy or religious claims that they’ve even seemed to suggest that clear evidence of insincerity must not be considered. The owners of Hobby Lobby and the administrators of Wheaton College happily provided contraception coverage for years before one day, abruptly, pulling a 180 and claiming that even a three-steps-removed involvement in the provision of such coverage would violate their suddenly newfound deepest religious convictions.

That’s ridiculous. It’s evidence that their purported free exercise claims are just as baseless as Markus Bishop’s claim that Club Amnesia is a church, or the claims of lazy Garden State parents that they forgot to vaccinate their kids because of religious reasons. And courts aren’t supposed to ignore evidence.

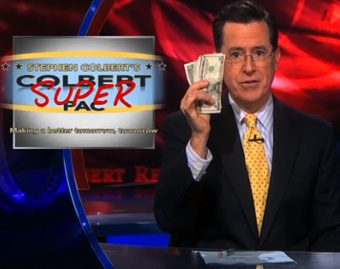

But the Supreme Court has now suggested that even such demonstrably insincere claims of sincerity must be treated as sincere. That encourages every huckster and opportunist who can find an angle to exploit religious exemptions for every penny. It creates a legal atmosphere that invites the religious equivalent of the Colbert Super Pac — Stephen Colbert’s giddily absurd, but perfectly legal, performance-art exploitation of post-Citizen’s United campaign-finance laws.

And that, ultimately, corrodes religious liberty. When legitimate religious exemptions are flooded with insincere claims whose legitimacy is never allowed to be legally considered, then those legitimate exemptions begin to seem less legitimate.

Again, I fully appreciate why the courts have been reluctant to involve themselves in questions of religious sincerity. But refusing to perform a necessary task because it is difficult doesn’t make the problem go away. A presumption of sincerity is probably a Good Thing. A presumption of sincerity that is impervious to clear evidence of insincerity is a recipe for disaster.