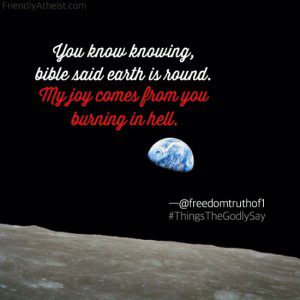

So I was reading this dismaying post from Tracy Moody — “The Most Disturbing Messages From Christians Found on the #ThingsTheGodlySay Hashtag,” which is just what it says on the cover — and thus I was trying to remember the name of that infernal doctrine that the saints in Heaven will watch, and rejoice in, the eternal torment of the sinners in Hell. But I couldn’t remember the name of the idea, only that it’s an appropriately awful, gloriously pious euphemism for the most despicable, venal sentiment imaginable.

[Here is where I will update this post with that name I can’t remember after some of you brilliant folks remind me of it in the comment section. It’s _____________________. Thank you.]

The inability to remember this sent me deep down a Google hole. Alps on alps arose and I wound up losing an hour reading all sorts of wretched things from folks like Tertullian and Jonathan Edwards. And all of that led me, somehow, to a strange, unsourced, curious theory about Edwards’ most famous sermon and the so-called Conspiracy of 1741.

The inability to remember this sent me deep down a Google hole. Alps on alps arose and I wound up losing an hour reading all sorts of wretched things from folks like Tertullian and Jonathan Edwards. And all of that led me, somehow, to a strange, unsourced, curious theory about Edwards’ most famous sermon and the so-called Conspiracy of 1741.

So first we’re going to have to talk about the New York Conspiracy of 1741. This may have been a slave revolt. Probably not, though. It seems it was probably just a white mass hysteria sparked by the fear of a slave revolt. Our history of this event is a bit like the history of the Salem witch trials. All we have to go on are court records from the many trials and proceedings, and all those records really show us is how appallingly flimsy the supposed evidence is that anything happened at all and how eager the public seems to have been, despite that, to see lots and lots of people hanged and burned and gibbeted.

What happened was a series of fires in lower Manhattan in the spring of 1741 — a not altogether unusual thing in a city of wooden buildings heated by fire. A slave was seen fleeing one of those fires. That might simply have been the perfectly sensible act of someone who didn’t want to be trapped in a burning building, but it was interpreted as evidence that he had helped to set it and, probably also, that there was a massive conspiracy of slaves and Jesuits plotting the overthrow and destruction of the city. (New York, at the time, was a city of about 20,000 people, 2,000 of whom were enslaved.) PBS’ Africans in America series describes this as a Witchhunt in New York:

The government, in an attempt to expose the culprits, offered a handsome reward and, if necessary, a pardon to anyone who would name names. Authorities questioned Mary Burton, a 16-year-old white indentured servant (a servant contracted to work for a set amount of time). Promised her freedom and 100 [pounds], she revealed the plans of a vast conspiracy to burn down the city and kill whites. She pointed the finger at John Hughson, the owner of the tavern where she worked, Hughson’s wife, as well as two slaves and a prostitute who were regulars at the tavern. They were all tried by the New York Supreme Court. All denied knowing anything about the conspiracy. All were hanged.

The accusations continued. Authorities were particularly suspicious of persons with ties to the Spanish colonies or to the Catholic Church, for Protestant England was at war with Catholic Spain at the time. Five Spanish Negroes were implicated, convicted and hanged. A white teacher named John Ury was suspected of being a Jesuit priest in disquise and the instigator of the uprising. Mary Burton confirmed this. He was hanged. The list goes on.

The “witchhunt” ended when Mary began to accuse wealthy, prominent New York citizens. She was then granted her freedom and given her 100 [pound] reward.

Eighteen black [people] had been hanged. Thirteen had been burned to death. More than 70 had been deported [to slave plantations in the Caribbean].

The first hangings in response to this mass hysteria took place on May 2. The executions, public hangings and burnings at the stake continued until the end of August.

I never learned about any of this in school. I’d never heard of this at all until I spent part of a snowy weekend chasing a string of links that started with the depraved delight of some theologians and led me, circuitously, to an odd little anonymous website about the local history of Brattleboro, Vermont,* and an amateur historian’s confidently speculative unsigned essay about two significant events that took place far from there in the year of 1741.

The first of these events was the New York Conspiracy of 1741. The second was Jonathan Edwards’ preaching of his famous sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” The latter was something I learned about in school. Edwards’ sermon is excerpted and anthologized in many American history texts as an example of the sort of 18th-century revivalist sermons that helped to spread the Great Awakening. (It’s a pretty poor example of that, actually, since Edwards’ Calvinism prevented him from offering any sort of altar call or suggesting that his audience had any recourse for escaping the damnation they deserved.) The sermon also appears in most American literature anthologies because, well, they’re desperate to collect any scrap of anything that was written down before 1800.

Our friend from Brattleboro starts with a couple of facts in evidence. First, several historians have argued that Edwards’ sermon fits the rhetorical model of the American “execution sermon.” That, unpleasantly, is an actual genre of literature. Execution sermons were a thing that preachers in Edwards’ day sometimes preached, delivered to a full congregation with the condemned seated right up front. And they tended to hit many of the same themes that Edwards hit, hard, in his famous sermon. The theory that “Sinners …” was an execution sermon is still just a theory, supported by the style and content of the sermon, but — as far as I can tell — not yet supported by further evidence or reports on the occasion of Edwards’ composing and delivering it.

The second fact that our Green Mountain essayist rightly notes is that Edwards delivered this famous sermon on July 8, 1741 — right in the middle of the panic surrounding the supposed conspiracy in New York City.

Alas, this second fact leads our friend to make what seems to me to be an unfounded leap — that Edwards’ sermon is a response to, and an example of, the hysteria that was sweeping New York, and that it was intended to address that situation directly. That’s a fascinating claim — intriguing enough that it sent me on another long Google chase. Yet I haven’t found anything, anywhere, to support the assertion this essay makes of a direct connection.

The essay includes some factual claims that are almost certainly wrong. It never quite contends with the distances involved — Edwards was preaching in Enfield, Connecticut, more than 130 miles from New York in an age when that was a formidable distance. And it fails to offer any supporting evidence from Edwards’ own writing, or from other contemporary accounts.

So, despite our friend’s confident tone, I can’t endorse their theory. I don’t see any evidence to support the idea that Edwards’ New England sermon is, in any way, directly related to the events then unfolding in Manhattan.

And yet.

That second fact above remains a fact — a vitally important fact that I’ve never previously encountered in any of the many, many discussions I’ve read of Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” And while there’s nothing to suggest that Edwards was directly affected by the hysteria in New York, news of it had reached New England, where slave-owning white people like Edwards himself were unsettled by the prospect of slave revolts.

The theory argued by our friend at Brattleborohistory.com is riddled with errors, unsupported by the evidence, and almost certainly very wrong. But it’s also certainly less wrong than every other thing I’ve ever read about Jonathan Edwards and “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Because every other thing I’ve read about that famous pastor’s famous sermon approaches it from the pretense that it is insignificant and not worth mentioning that this is the sermon of a slave-owner delivered at a time when the northern colonies were gripped with the fear of slave revolts. And the contention that none of that had any influence on Edwards, on Edwards’ theology, or on his composition and delivery of this particular sermon, is more outlandishly absurd and patently false than anything suggested in that unreliable essay.

Anyway, I still can’t remember the name of that odious theological theory about the saints in Heaven delighting in the spectacle of sinners suffering in Hell. Help me out with that.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* While I can’t agree with the thesis of the site’s essay on Edwards’ sermon, I do commend the rest of the site for its terrific collection of early photographs of Brattleboro, which is a charming place with a Main Street that Hollywood location scouts really need to see.