I grew up in the New York media part of New Jersey, so I’ve been watching Donald Trump on my TV since I was in junior high. He was a character then — a shamelessly self-promotional, gold-plated hack who embodied the coke-fueled get-rich dreams of Manhattan Yuppies back when the word “Yuppies” was still a thing.

That Donald Trump was a different creature from the Donald Trump now favored to win a majority of Repubican delegates on Super Tuesday. That earlier version of Trump was, like the current one, a boorish blowhard with a flair for garish tackiness that he relentlessly insisted was “classy.” But he hadn’t yet become the demagogue we see today.

In the ’80s and into the ’90s, Trump made a name for himself as someone desperate to make a name for himself. He seized on the idea that there’s no such thing as bad publicity and ran with it, willing to engage in whatever ridiculous antics it took to spark another round of the ridicule that kept his name in the papers. He made himself synonymous with a string of splashy failures — bad ideas and bad decisions aggressively pursued until their eventual collapse.

The epitome of 1980s Trump was probably his ownership of the New Jersey Generals — New York’s franchise in the upstart USFL, the professional football league that sought to compete with the NFL. Trump put himself front and center, as always, as the winning winner who would build a winning team. Then he sold his stake in the team to someone else and walked away to pursue some real estate deals instead. In his absence, the team drafted Heisman Trophy winner Herschel Walker — outbidding the NFL in a move that suddenly made the Generals and the entire USFL seem viable. That’s when Trump returned as owner and began pushing for the league to abandon its spring schedule to compete head-to-head with the NFL by playing in the fall. Trump’s big plan was that this move would force a merger with the NFL, producing a bonanza of profit for USFL investors.

That didn’t happen. The league’s 1986 fall schedule never happened. It folded. The anti-trust lawsuit against the NFL that Trump insisted would produce a windfall for team owners and force a lucrative merger wound up being settled — for $3.

That was pretty much the pattern for every subsequent Trump venture — a bunch of pushy, headline-grabbing publicity moves, followed by stubborn litigious maneuvering, erratic involvement and, ultimately, financially disastrous decisions and failure. And it was all wrapped in this boisterous attempt to redefine crude selfish greed as “classy” — an effort that was about as effective as the way strip clubs grasped for respectability by rebranding themselves as “upscale gentlemen’s clubs.”

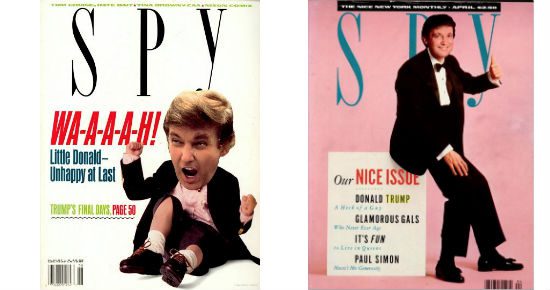

Trump became more of a punchline as he seemed stuck in the ’80s well into the ’90s. That’s when Spy magazine made Trump its whipping-boy as the incarnation of everything that was wrong with Manhattan. Bruce Feirstein recalled that long-running feud last summer in “Trump’s War on ‘Losers’: The Early Years“:

In 1988, Spy magazine described Donald Trump as “a short-fingered vulgarian.” The founding editors of the magazine, Graydon Carter and Kurt Andersen, recognized Trump for what he was: the id of New York City, writ large— a bombastic, self-aggrandizing, un-self-aware bully, with a curious relationship to the truth about his supposed wealth and business acumen. He wasn’t so much a Macy’s balloon, ripe for the targeting, as he was the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man from Ghostbusters, stomping on everything in his gold-plated path. …

Today, 27 years and a reality-TV show later … he’s become the dark, nasty id of America itself: uncensored, unthinking, bullying, angry, forever unapologetic, and vaguely unhinged.

I’ve read dozens of articles over the past few months arguing that Trump is no longer funny. And dozens more responding to those by saying that Trump was never funny. But Trump wasn’t a running joke for Spy magazine because he was funny, he was a perpetual punchline because he was a lot ridiculous and also more than a little bit dangerous. He was a transparently clownish clown, but also a reckless cretin with a propensity for punching down — for exploiting workers and tenants, for enriching himself though a string of failures that always seemed to become somebody else’s problem. He was the real-life incarnation of Fitzgerald’s description of Tom and Daisy Buchanan in Gatsby: “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Even so, the Donald Trump of the ’80s and ’90s was still a creature of Manhattan. He was a bully and a jerk who was prone to saying ghastly things about women and “the blacks,” but he lived and worked in a cosmopolitan city that required him to reject the kind of explicitly, defiantly racist ideology that he’s come to embrace in more recent years.

This weekend, Trump appalled everyone capable of being appalled by refusing to distance himself from the endorsement of former Klansman and current white supremacist David Duke. Trump claimed that he’d never heard of Duke — an obvious lie because years ago Trump had explicitly cited Duke’s involvement in the Reform Party as the reason for abandoning his short-lived, publicity-seeking “campaign” for president under their banner. That 2000 statement rejecting Duke is now being cited as proof that Trump was lying yesterday when he said “I know nothing about David Duke.” But I think it’s more important as evidence of how much Donald Trump has changed over the past 16 years. The mostly ridiculous and somewhat dangerous clown from the 1980s has evolved into a still-ridiculous, but far more dangerous, demagogue.

Some of us saw that change occurring as it happened — as he dove into birtherism following the election of President Obama. There has never been any non-racist basis for birther conspiracy theories about the first black president, but since that foolishness was so widespread among tea party Republicans, it was long treated as just a matter of legitimate partisan dispute — another matter to be addressed through he-said, she-said journalism that gives equal credibility to both sides of the issue.

So for many observers — including much of the New York media and the Republican “establishment” — Trump’s transformation into an explicitly racist, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim demagogue went unnoticed until it was too late. They saw him as nothing more than the buffoon and 1980s-relic they remember reading about in the pages of Spy.

Their failure to trace the transformation of Trump was, in some ways, understandable. The man’s inexhaustible demand for attention had long since exhausted most people’s ability to keep pace. Keeping track of his every move seemed about as rewarding and significant as wondering whatever became of Marla Maples and her “No Excuses” jeans. A billionaire-turned-reality-TV-star-turned-birther-crank didn’t seem likely to re-emerge as the politically significant reincarnation of George Wallace.

This is why I like John Oliver’s segment on Trump from the weekend’s Last Week Tonight on HBO. Oliver recognizes why it took too long for so many people to take Trump and his candidacy seriously, but makes a strong case that it’s not too late to wake up and smell the Drumpf:

I know that many of my fellow Democrats regard Trump’s leading role in the GOP primary season as good news, since it likely increases the odds of a Democratic victory in November. It probably does, but this still scares the bejeezus out of me for at least three reasons:

1) Trump’s campaign isn’t just relying on widespread racism and xenophobia. He’s whipping it up, feeding and nurturing and promoting it. He didn’t invent or create this, but he’s making it even worse. That’s doing real harm to real people, regardless of the outcome in November.

2) Once he secures the Republican nomination, there’s a chance he could win in the fall. Sure, he’s got sky-high negatives for a national campaign, but the partisan divide is still starkly partisan. Maybe a Trump nomination will make people like David Frum or David Brooks cross the aisle to vote against him, and maybe a percentage of other Republicans will just decide to stay home. But he’ll still be the nominee of one of our two parties, and that gives him a credible chance to win.

3) Trump’s nomination would transform a good chunk of the currently anti-Trump Republican electorate into something more Trumplike. That happens. I knew a lifelong Republican who fought for Gerald Ford in 1976, fiercely opposing the primary challenge from Ronald Reagan, whom he viewed as a dangerous, radical kook and the embodiment of everything that was wrong with that wing of the party. In 1980, he supported George H.W. Bush in the primary, cheering Bush’s rejection of Reagan’s “voodoo economics.” But by 1984, he was a Reaganite through-and-through. That happens. And, despite the current, belated Republican “establishment” panic over Donald Trump’s success, it’s already begun happening again.