Syndicate Theology’s* latest symposium is on religious historian Grant Wacker’s sort-of-biography of Billy Graham, America’s Pastor. It’s pretty terrific, with thoughtful and thought-provoking contributions and assessments from Vincent Bacote, Randall Balmer, Nathan Walton (not posted yet), and Kathryn Lofton, and well-considered responses to each from Wacker himself.

Lofton’s essay crackles. Academic writing isn’t always a joy to read. This is:

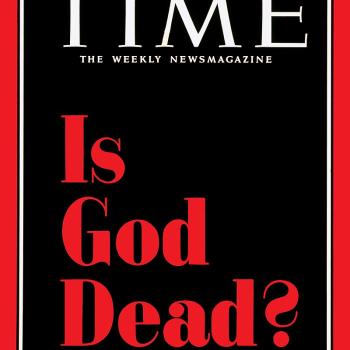

Wacker suggests that Billy’s persuasive power is his confidence, and that maybe what everyone can’t stop enjoying is the pleasure of borrowing from his seemingly unceasing well of certitude. Wacker calls Graham “humble” several times, but this wouldn’t be a word anyone would use who watched Billy preach. I think humble is a word that describes well Wacker’s relationship to his subject and to religious actors generally, but humble Graham is not. Billy is ferociously certain about a view of the world that is encompassing of everyone in it. During his heyday as a circulating preacher, Graham articulated confidently a series of simple theological ideas: that you only need one text to understand all things; that this text is very clear; that Jesus was sinless and he paid for our sins; that if you repented you’d have a better life; and that life everlasting would be better than this life. And, most of all, Graham repeatedly expressed the idea that “Christians could be confident that Christ would return at the end of human history.” It is a bundle of news offered as the Good News.

She presents a compelling, persuasive critique of Graham as a kind of embodiment of this ferocious certitude, with all the incuriosity that entails. The terrific thing about Syndicate’s format, though, is that it also provides Wacker’s response to Lofton’s essay, which is also often persuasive in sanding some of the edge off of her sharp critique. The exchange of ideas here is worth reading in full, demonstrating, perhaps, why being confident is a virtue, but being “ferociously certain” is not.**

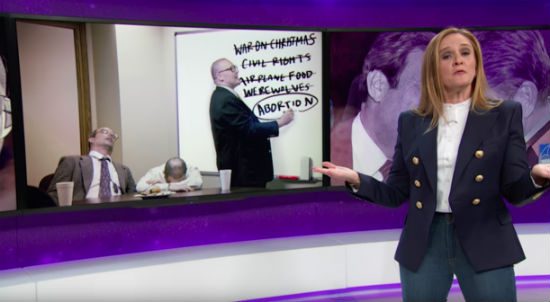

The exchange on Lofton’s essay is particularly interesting in light of Wacker’s earlier response to Randall Balmer’s essay assessing “Billy Graham and the Judgment of History.” You may have seen Balmer recently on late night TV (or on YouTube, because that’s how late-night TV works now), when he was featured in a Samantha Bee’s fiercely funny segment on the history of the religious right:

Bee’s segment has all the subtlety you might expect from a show called Full Frontal, but it ain’t wrong.*** She offers a snarky, entertaining crash course in Balmer’s ever-more-convincing thesis about the rise of the religious right. Somebody on the Full Frontal writing staff has been reading Balmer (and maybe also sometimes this blog, as Bee’s abortion-as-retroactive-proxy-for-opposition-t0-civil-rights theme is happily familiar).

Bee’s comedy segment is relevant to the academic discussion at Syndicate because she allows us to see the fruit of Billy Graham’s behind-the-scenes politicking as it played out in the 1980 election. Here’s Balmer’s account of Graham’s role in that process:

Long before the 1980 campaign, Graham convened a dozen fellow preachers in Dallas for “a special time of prayer” and talk about the upcoming presidential campaign. Carter’s liaison for religious affairs had only recently returned from a visit to the evangelist’s home in Montreat, North Carolina, with a report that Graham “supports the President wholeheartedly.” But that support was apparently less than robust. The Dallas guest list, formulated by Graham himself, included his brother-in-law, Clayton Bell; Rex Humbard and James Robison, both of them televangelists; and a roster of well-known Southern Baptists: Charles Stanley, Jimmy Draper, and Adrian Rogers, the new president of the Southern Baptist Convention, who had recently visited Carter at the White House and declared it “one of the highlights of my life.” The ministers, gathered at Graham’s behest, occupied nearly an entire floor of the hotel. “It really was Billy’s meeting,” Robison recalled. “What he wanted us to do was pray together for a couple of days and to understand something very significant had to happen.” The unmistakable subtext of the gathering was the need to rally behind someone who could mount a challenge to Carter. The upshot of the meeting was an overture to Reagan encouraging him to challenge Carter for the presidency.

The James Robison quoted there is the same culture-war flamethrower shown in Bee’s segment, the guy who says this, as candidate Reagan smiles and applauds: “I’m sick and tired of hearing about all the radicals, and the perverts, and the liberals, and the leftists, and the Communists coming out of the closet. It’s time for God’s people to come out of the closet, and the churches, and change America!”

(Robison invested that word “radicals” with as much fear-inducing danger as he could, but, still, it seems less inherently insulting than most of the religious right’s other euphemisms for black people.)

In Wacker’s response to Balmer, he cordially disagrees with the idea that Billy Graham played much of a role in the rise of the religious right:

Is Graham responsible for the rise of the Christian Right? The answer is partly yes, but mostly no. Clearly he helped create the public space that it came to inhabit. Yet Graham himself stayed out of it, refusing to endorse its aggressive partisanship and narrowness of vision. … Should he be charged with the sins of his successors? I think not.

Note what Wacker here does not and cannot disagree with: the creation of the religious right is a matter of blame. “The sins of his successors” are, indubitably, sins, and Wacker is not inclined to try to defend them.

But he does minimize those sins, characterizing them as simply “aggressive partisanship and narrowness of vision.” That’s not quite responsive to Balmer’s charge. Balmer isn’t bemoaning an overly aggressive tone or “narrowness of vision,” he’s pointing out that the religious right is hateful, racist, misogynist, and nationalist. That’s why the Robison clip in Bee’s piece matters here — it shows us what they’re both describing. And what we see supports Balmer’s description more than Wacker’s.

Their different assessment of the severity of the “sin” of the religious right is reflected in their different assessments of Billy Graham’s complicity in it. For Wacker, it is unfortunate that Graham “helped create the public space that it came to inhabit.” But for Balmer — and for me — that’s a bigger failing. In our view, Graham helped create a public space that was hospitable to the anti-feminist, anti-civil-rights, anti-gay, anti-poor viciousness of the religious right. That suggests that there was something about Graham’s gospel theology that was able to accommodate such oppressive hatefulness or, at best, that there was nothing in Graham’s gospel theology that was explicitly opposed to it.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Syndicate Theology is a remarkable thing. They pick a topic — a book, an idea — and invite several different people from varying perspectives to write about it and to respond to one another.

No, that’s not a novel format. It’s basically the same thing that happens at thousands of academic conferences every year. But this is a really good academic conference, one you can sit in on for free, at your convenience and in your pajamas. And over the course of its first year, the quality of contributors and their contributions, the tone and the substance of robust disagreements, and the range of subjects they discuss, have all been first-rate.

Every discipline should have one of these.

** One fascinating side-note in Wacker’s response is his citation of Gallup polling in support of Billy Graham’s national stature, respect, and respectability:

Between 1955 and 2015, Graham appeared on the register of “Most Admired Man in the World” 59 times, nearly twice as often as any other person.

That’s true — Graham does hold the record for most appearances in Gallup’s annual “Most Admired” lists. And Wacker isn’t the only one who cites this as evidence for the respect and deference due to Graham as a person of widely acknowledged integrity.

But while he’s consistently landed somewhere in the Top 10, he’s never actually claimed the top spot as the “Most Admired.” He’s never been No. 1 on that list. (Graham is like the Jim Kelly of Gallup polling.) The record for most appearances at No. 1 on those lists — by a lot — belongs to Hillary Clinton: “Clinton has been the most admired woman each of the last 14 years, and 20 times overall, occupying the top spot far longer than any other woman or man in Gallup’s history of asking the most admired question.”

It’s interesting that none of the evangelicals who cite Billy Graham’s “record-breaking” admiration in Gallup polls ever seem to notice that the same thing — with all the same implications — can be said for Hillary Clinton. I guess that’s because “everybody knows” that “everybody hates” her (except for the record-breaking number of Americans who have volunteered their admiration for her “far longer than any other woman or man” in the history of such polling).

*** The one aspect of Bee’s history lesson that I’d challenge would be the rehashing of the conventional wisdom about a 50-year fundamentalist retreat from politics after the Scopes trial and the repeal of Prohibition. It’s true that white fundamentalists weren’t trying to influence national politics from the top down during those years, but white fundies were still very active against everyone from FDR to MLK. Maybe we didn’t see Jerry Falwell saying, as he later would, that getting (white) Christians registered to vote was an essential mission for the church, but from the ’30s through the ’80s, white fundamentalists were extremely active in preventing black Christians from being able to do so.