I am very pleased to have (belatedly) discovered Ask An Entomologist on Twitter (the same fine trio also blogs at askentomologists.com). Do you have bug questions? They can provide bug answers. Awesome. This will come in very handy during warmer weather, when I’m spending a lot of time in my favorite reading/writing chair on the porch.*

I encountered these friendly neighborhood scientists thanks to a fascinating thread on beekeeping, history, science, and — in a sense — hermeneutics. It’s about how scientists were finally able to see what they were seeing, and about what had long prevented them from being able to see what they were seeing. So this also has something to teach us about how we see or don’t see other things, like the meaning of texts.

I’m not sure which member of the @BugQuestions team actually wrote this, but here’s a good bit of their Twitter thread transcribed into non-Tweet form:

What we now call “queen” bees — the main female reproductive honeybees — were erroneously called “kings” for nearly 2,000 years. Why? Let’s explore the history of bees!**

We’ve been keeping bees for 5,000 years+ and what we called the various classes of bees was closely tied to the societies naming those classes. For instance, in a lot of societies it was very common to call the “workers” slaves because slavery was common at the time.

This segues into a discussion of Aristotle’s understanding of bees, which was taken as authoritative for centuries. Aristotle was sure that the biggest bees, the leaders of their colonies, had to be male:

Without going into all of his views on the topic, it’s apparent his views on women pretty heavily influenced what he saw was going on in the beehive. He thought of reproduction as a masculine activity, and thought of women as property. He just wasn’t very objective about this.

So, when he saw a society led almost entirely of women it actually makes a lot of sense as to why he saw the “queen” bees as male and called them kings. These ideas of women in his circle were so ingrained that a female ruler literally wouldn’t compute.

… Today it’s completely and 100-percent accepted that queen bees are, in fact, female, and that the honeybee society is led by women. What changed in Western Society to get this idea accepted?

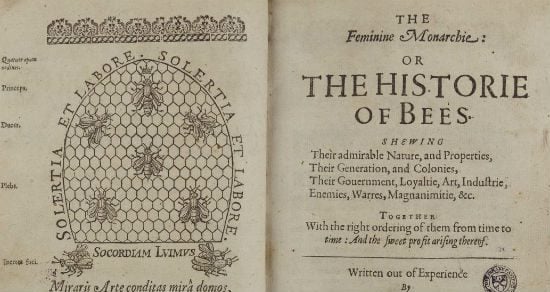

The exact work which popularized the (scientifically accurate) idea of the honeybee as a female-led society was The Feminine Monarchy, by Charles Butler. However, I’d argue this lady also played a role.

“This lady” there refers to Queen Elizabeth I, who reigned as monarch for most of Butler’s life:

The fact that Charles Butler was interested in bees, and lived under a female monarch for most of his life, I think played a major role in his decision to substitute one simple word in his book.

That substitution? He called “king bees” “queen bees,” and it stuck.

At this point in Europe’s history, there had been several female monarchs so the idea of a female leader didn’t seem so odd. Society was simply primed to accept the idea of a female ruler.

Charles Butler was a fascinating guy. Simon Brackenborough has a great discussion of him here. He was a clergyman and a music theorist as well as a naturalist. He even managed to combine all of his disparate passions into one composition, “The Bees Madrigal“:

But if the reign of QE1 finally set the stage for finally recognizing that “king bees” were actually queens, her reign may have also contributed to something else that Butler and others of his time were still as-yet-unable to see. As @BugQuestions explains, it took more than 100 years after Butler for anyone to understand what they were seeing about the way honeybees reproduce. After Butler comes the brilliant biologist Jan Swammerdam, who actually studied the reproductive organs of queen bees and male drones, yet:

Despite this important discovery, Swammerdam wasn’t convinced bees had sex.

So here’s this guy studying bee biology, and working out the details of their reproductive organs. He’s not convinced bees have sex.

What the hell, right? Why does he think that?

Well, again, Queen Elizabeth. Queen Elizabeth was known as the “virgin queen,” and this idea also influenced Charles Butler who couldn’t reconcile the idea of a queen giving birth with what he observed in a beehive.

Even though beekeepers, for thousands of years, had observed queen bees mating and laying eggs, our science was unable to see what we were seeing because non-virginal female leaders weren’t something we were prepared to accept.

Here’s the punchline, and the application — which goes well beyond just entomology and science:

At every step along the way, we can show that the social environment of the observers kept them from seeing things that are obvious to us today. The social environment of the time kept the society from accepting some rather obvious observations.

What we see — what we are able to see and what we are willing to see — is often determined by our social environment.

Keep that in mind the next time you see someone pontificating about what “the Bible clearly teaches.”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* My current methods for identifying the odder creatures gathering around our porch light have been: 1) Squinting to compare pics taken with my phone with Google image searches for things like “pretty bug beetle orange spots;” and 2) Asking them directly (“Ooh, you’re pretty. What are you?“). The first method has been only marginally more successful than the latter, so having a team of enthusiastic, friendly entomologists on-call seems like an improvement.

Scrolling through their Twitter feed I see that these folks also cheerfully and helpfully respond to spider questions without getting all pedantic about insects vs. arachnids. So they’re more like that really good science teacher you had if you were lucky back in school, rather than like that other teacher you had if you weren’t.

** As a general rule, I believe that exclamation points should be presumed guilty until proven innocent. But my !-skepticism melts away when encountering sentences like this one, written by someone who has earned that emphatic enthusiasm, that boom de yada, and is eager to share it with the rest of us.