The book of Daniel is apocalyptic literature. Usually we think apocalyptic literature as end of the world destruction. That could be a part of it, but apocalypse really means “Revealing” or “Unveiling.”

The book of Daniel is apocalyptic literature. Usually we think apocalyptic literature as end of the world destruction. That could be a part of it, but apocalypse really means “Revealing” or “Unveiling.”

Daniel reveals the truth about human relationships, specifically about human violence.

Violence is the big problem in Daniel, as it is throughout the Bible. From the beginning to the end of Daniel, we see violence. And the point of Daniel is to explore how the faithful people of God should respond to violence. Daniel says we should respond with nonviolent protest.

In chapters 1-6, Daniel and his people are conquered by the Babylonian empire. They are taken from Jerusalem and spread throughout the empire. Daniel ends up responding to this violence not with his own violence, but by working his way up through the ranks of the Babylonian empire, to become an advisor to the king.

In chapters 7-12, Daniel has apocalyptic visions. In the end times, Kings of the North and the South battle one another. They are locked in what Rene Girard calls a mimetic, or imitative, rivalry of violence. One defeating the other, and the other winning in a battle. The war goes back and forth between these two kings in an escalating rivalry of violence.

The book even says “evil shall increase.” From the beginning of Daniel to the end, there is an apocalyptic warning about violence. Human violence will eventually destroy the world.

How should the faithful respond to this violence? With nonviolence.

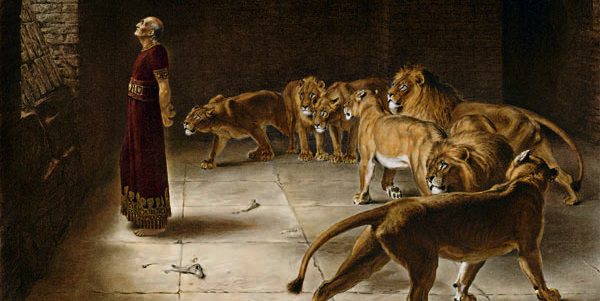

Daniel responds with nonviolence. Take the story of Daniel and the lion’s den, for example. Daniel has worked his way up to become an advisor to the king. Other advisors are jealous of Daniel’s relationship with the king. They turn against Daniel. They unite against him in an act of scapegoating. They tell the king that he should make sure that everyone prays only to him.

Daniel, as a good Jew*, isn’t going to pray to the king. Instead, he’s going to keep praying to his God. The people who are jealous of Daniel know he will pray to his God. They catch him in the act and they tell the king. The king then throws Daniel into the lion’s den.

Daniel trusts that God is going to be with him in the lion’s den. He doesn’t respond to violence with violence of his own. He doesn’t respond with anger or resentment. He just goes into the lion’s den, trusting that God will be with him.

Daniel survives, but the king is locked into violence. He ends up killing not only the men who united against Daniel, but also their wives and children.

A similar pattern happens with Daniel’s friends Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. The king creates a golden statue of himself and making everybody worship the statue. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, as good Jews, refuse to participate in this form of national worship. They only worship their God. Others who are jealous of the three friends see that they refuse to worship the statue. They tell the king, who sends them to the furnace.

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego say to the king that they will go into the furnace, and that their God may or may not save them. They had doubts, but the most important thing was to show the king that they wouldn’t give their lives to him. Rather, in an act of political protest, they gave their lives to God.

They went into the furnace and survive. A fourth person, a godly figure, joins them. The kings saw the fourth person and says that their God, the true God, was with them the whole time. He let them out, and then said that if anyone says anything against their God, he would tear them “limb from limb.”

Once again, the king is stuck in violence. This pattern of violence happens repeatedly in Daniel. Soon the pattern leads to the apocalyptic visions of chapters 7-12. The kings are stuck in a rivalry of apocalyptic violence against one another that could destroy the world.

How are we to respond to that violence? Daniel has already made the case for nonviolent protest, but there is more. Earlier, Daniel went up to the king and told him that he could atone for his sins by giving “mercy to the oppressed.”

Challenging political rulers to care for the marginalized and oppressed is part of the prophetic nonviolent protest that we see throughout the Bible.

Another way to respond to violence is found in chapter 11. When the King of the North and the South are locked in a violence battle, it’s almost as if the people of God are standing back and watching it happen because their mutual violence will cause their own destruction. But chapter 11 says the people are supposed to “take action.”

But their action isn’t violent. “The wise among the people shall give understanding to many.” Understanding of what? In the apocalyptic visions, God tells Daniel to not be afraid. That people may die, but don’t give into violence. Do not be afraid. Stay true to your mission, which is to stand with the oppressed and protest political corruption nonviolently.

Daniel ends with this teaching, “Happy are those who persevere.” For violence will come. God calls us not to mimic that violence, but to persevere with love and nonviolence.

For more videos in the Bible Matters series, click here.

Stay in the loop! Like Teaching Nonviolent Atonement on Facebook!

Image: Wikimedia, Daniel, by Britton Riviere, Public Domain.

*Daniel wasn’t technically a Jew. Judaism as we know it took form in the 1st century. The technical term for Daniel is “Judahite,” since he was from the land of Judah. But the term Jew is easier than Judahite, so I use it here.