Editor’s Note: Another great post by The High Calling summer intern, Nathan Roberts.

Editor’s Note: Another great post by The High Calling summer intern, Nathan Roberts.

“Internship at the production company of an Oscar-nominated director”

I stared at the notice on NYU’s job and internship database. It was my second semester, freshman year, and high school graduation gifts were dwindling. I needed a job. Like, a job job. But as I fervently tossed resumés into cyberspace, I figured I’d try an offhand search for paid internships, too. This post appeared like a beacon of hope: a paid internship? With an Oscar-nominated director? My hopes weren’t high, but I sent them my resume.

I didn’t hear back from the twelve other “job jobs” I applied for, but I did hear back from Warrior Poets.

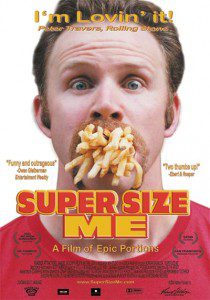

So I walked along a steady stream of trendy, modernist SoHo boutiques; squeezed into a dirty, rickety metal elevator; and stepped into Morgan Spurlock’s production company office. Remember him? He’s the guy who ate nothing but McDonalds for a month and got an Oscar nom for it. The interview was pleasant, I was available when they needed me, and I got the job––I mean, internship. In reality, the word “paid” was a bit misleading. Interns were to receive ten-dollar stipends for every eight-hour workday clocked in. In salary terms: 1.25 dollars per hour.

“You know, enough to cover travel costs or lunch costs,” they cheerfully explained.

Just enough to cover a large #2 meal at McDonalds, I thought.

The Unpaid Student Workforce of New York City

Unpaid internships are a dime a dozen in New York City. I’m not sure when they became so popular, but they’re everywhere. Many of my peers go to NYU just so they can intern. Interning is such a large part of campus culture that you can feel a bit naïve and unproductive if you don’t intern. We may even intern for school credit, if we so desire. That’s right: we can pay thousands of dollars to work for free.

Unpaid internships are a dime a dozen in New York City. I’m not sure when they became so popular, but they’re everywhere. Many of my peers go to NYU just so they can intern. Interning is such a large part of campus culture that you can feel a bit naïve and unproductive if you don’t intern. We may even intern for school credit, if we so desire. That’s right: we can pay thousands of dollars to work for free.

But, as you might’ve heard, unpaid internships have been stirring up steady controversy. Many people think it seems unfair (and occasionally illegal?) to hire people to work for less than minimum wage. How was it right for Sheryl Sandburg––feminist workforce cheerleader of the decade––to offer unpaid internships at her Lean In foundation office? When revealed in a Facebook post, the Lean In internship caused a critical maelstrom: “Why does Lean In offer an unpaid internship? Really? I thought women should lean in and demand more money. Unpaid work, be it internships for young women or volunteer positions for older moms, is exploitive. Shame on Lean In. Pay up.”

Some of my peers have decided to take a stand against this sort of “exploitation.” But most of my fellow undergrads merely grin and bear it––or, more accurately, sigh and bear it.

Turning People Into Commodities

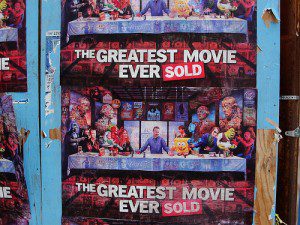

In the Warrior Poets office, colorful pop art covers exposed-brick walls. Fat, gleaming, plastic Ronald McDonalds’s lounge on Morgan’s shelves. A couple months into the intership, I help carry up “Morgan’s Last Supper” from his car: Morgan is depicted in Christ’s seat, joined by his disciples Spongebob, Buzz Lightyear, Darth Vader, Shrek, and so on. Above them tower portraits of U.S. presidents, molded out of dollar bills and comic strips. This painting, by Ron English, was featured in a Spurlock-curated art show. While it kind of feels like Andy Warhol hitting you over the head with a sledgehammer, it’s easy enough to interpret: religious devotion has been swapped for pop culture devotion, and what does pop culture worship? Money.

In the Warrior Poets office, colorful pop art covers exposed-brick walls. Fat, gleaming, plastic Ronald McDonalds’s lounge on Morgan’s shelves. A couple months into the intership, I help carry up “Morgan’s Last Supper” from his car: Morgan is depicted in Christ’s seat, joined by his disciples Spongebob, Buzz Lightyear, Darth Vader, Shrek, and so on. Above them tower portraits of U.S. presidents, molded out of dollar bills and comic strips. This painting, by Ron English, was featured in a Spurlock-curated art show. While it kind of feels like Andy Warhol hitting you over the head with a sledgehammer, it’s easy enough to interpret: religious devotion has been swapped for pop culture devotion, and what does pop culture worship? Money.

So, ironically enough, I found myself the unsalaried employee of a filmmaker interested in the ever-present allure of money. Spurlock’s first film, Super Size Me, successfully took one of the world’s largest corporations, McDonalds, to its knees. He produced What Would Jesus Buy?, a bemused examination of our commercialized Christmastide. In his most ironic, had-his-big-mac-and-ate-it-too film, Spurlock directed POM Wonderful Presents: The Greatest Movie Ever Sold. This clever troll of product placement was chock-full of, and completely funded by, product placement. Spurlock appeared on talk shows and at film festivals sporting his logo-saturated jacket, POM’s funky emblem front-and-center. There was, and probably still is, a fridge in the Warrior Poets office constantly stocked with POM Wonderful. It’s on the house. (I became a fan of POM’s lesser-known beverage, Pomegranate Lychee Green Tea.)

Spurlock is interested in what social critics sometimes call Late Capitalism. Beneath their debatable economic talking points lies a deeper concern. They fear the day when, as Zadie Smith succinctly puts it in an essay on David Foster Wallace, “the logic of the market seeps into every aspect of life.” The “logic of the market” values assets and commodities, but only insofar as these things reap profits. Commodities, like computers and groceries, have little innate worth. These things are valuable so long as they help us, but we can thoughtlessly discard them when they’ve worn out their welcome.

But when this mindset seeps into everyday life, we treat people like consumable or disposable commodities. They’re only valuable if and when they suit our needs. This isn’t some abstract philosophical concept; we have common terms for this sort of denudation. One of them is “objectification.” A woman is literally objectified when she’s reduced to “a nice pair of legs.” A misbehaving student becomes “a bad apple.” In Toy Story, Andy swaps Woody for Buzz Lightyear because Buzz is the newer, better, trendier thing. We’re in on the tragedy, though: Woody isn’t just a thing. Woody is a living thing.

Commodification is selfish. We don’t serve commodities; commodities serve us. Therefore, when we treat people like commodities, we think: “How can this person help me?” “How can this person fit my needs?” “What am I getting out of this relationship?”

Internships as Commodities

In my time at NYU, I have never heard someone call his or her internship a “volunteer position.” Instead, we use the word “internship” because it sounds professional. It sounds productive. It might even be paid. (Full disclosure: I’m actually writing this article for an incredible paid internship at The High Calling––which, by the way, is funded by a grocery chain that works extremely hard to avoid commodifying its employees and local communities.)

We use the word “internship” because it gives off the impression that we’re actual job market players. We may or may not be salaried, but we have our chips in the game, and that’s what counts.

The New York job market turns the gears of the Internship machine. The logic of the market still reigns. Students treat internships like commodities to be acquired: “I got this internship,” we say. We tell ourselves (over and over again) that internships give us competitive advantages: experiences, connections, resumé additions. If we work hard enough to please our bosses? We get job recommendations. Cha-Ching.

We strategize and connive and dream because, if we’re not getting anything out of these unpaid jobs, we’re fools. We’re exploited fools trudging through the rain in order to grab trays of complicated Starbucks orders. That’s all.

Every once in a while someone––when this someone isn’t hindered by political sensitivity––compares unpaid interns to slaves. (Apparently this happens publically and provocatively in the looser land of Canada.) Slavery is certainly the greatest, terrible case of mass human commodification the United States has had to grapple with. The “unpaid interns are actually slaves” argument suggests that interns are exploited in similarly one-sided ways. Bosses dangle the carrot of future employment in front of us. They make us trot along and profit from our labor, but they never let us eat the carrot. Interns are manipulated pawns in the corporate game.

Not only is this a straw man argument, but it’s reductive in an obvious, crucial way: unpaid internships are voluntary. Nobody forces us to intern. We aren’t slaves to external masters.

Enslaved and Freed

The truth is, fellow interns, we’re not enslaved to the market or enslaved to our bosses. We’re enslaved to our own dreams and visions of success. We’re slaves to our ambitious fantasies. And in the process, we commodify our employers as much as, if not more than, they commodify us. They’re just stepping-stones on our paths to glory.

The truth is, fellow interns, we’re not enslaved to the market or enslaved to our bosses. We’re enslaved to our own dreams and visions of success. We’re slaves to our ambitious fantasies. And in the process, we commodify our employers as much as, if not more than, they commodify us. They’re just stepping-stones on our paths to glory.

It’s not that “the logic of the market” has infiltrated our personal lives. Moral energy travels in the other direction, too: the logic of our hearts infiltrates the market. And our hearts are slaves to self-obsession.

I know this feeling all to well. Initially, I felt enslaved at my internship. I felt chained to my bosses’ approval, anxious to perform impressively, and longed to “make it” in the working world. It was an exhausting, stressful time. I felt consistently inadequate.

But, it began to dawn on me that, as a freshman without a film degree, Warrior Poets wasn’t going to hire me for the long term anyway. It would’ve been impractical for them and impossible for me. As this reality set in, my mindset slowly shifted. The internship was no longer a commodity I could manipulate for my own professional advancement. It was merely an opportunity for me to give. And as I began to think of myself as a volunteer––as a giver, not an anxious receiver––I began to breathe freely again.

The Peculiar Feeling of Rightness

After my last day of work, as I took my final sunset walk up Lafayette, back home, I felt a small, peculiar feeling of satisfaction in the pit of my stomach. It wasn’t because I had thought of Jesus through it all, or memorized Colossians 3:23 while sorting receipts and delivering equipment. My faith was far too tenuous for that. And it wasn’t just because my bosses were happy with me, although they were kind and pleased with my work.

After my last day of work, as I took my final sunset walk up Lafayette, back home, I felt a small, peculiar feeling of satisfaction in the pit of my stomach. It wasn’t because I had thought of Jesus through it all, or memorized Colossians 3:23 while sorting receipts and delivering equipment. My faith was far too tenuous for that. And it wasn’t just because my bosses were happy with me, although they were kind and pleased with my work.

I can only describe that small, warm feeling as a sense of rightness. Perhaps it was a hint of the rightness we’ll feel in a city where we’ll no longer call it “working for free,” but giving for the joy of the One who saw us in hopeless slavery, who knew we were damaged goods, and chose to purchase us for an immeasurable price. Perhaps it was a hint of the satisfaction we’ll get when we give for the pleasure of the One who was mocked and objectified so that we may be called holy and sacred.

Perhaps I felt the pleasure of the One who turned “the logic of the market” on its head, literally and figuratively (Matthew 21:12); the One who wasn’t just “ripped off” for us, but ripped open for us.

Perhaps it was a seed starting to gestate inside me, whose growth may one day cause me to look at my work, paid or unpaid, and say: I’m loving it.

Image credits:

- Super Size Me Poster- by Gaurav Mishra, via Flickr

- New York City- via Wikipedia

- Greatest Movie Ever Sold Poster – by Gladys Santiago, via Flickr

- Wall Street Subway – by Ed Schipul, via Flickr

- Manhattan Skyline at Sunset – by Ala Turkus, via Flickr

Working for Free

In this series, Working for Free, we’ll take a look at the different ways people navigate the world of working in a job they love, even when it might not be the way they make ends meet. Join the discussion or share your story in the comments. What do you think? Is passion enough?