The season of spring has arrived! The rites of fertility have begun! This is a holiday with a colorful past, and strangely enough, one of the only major festivals on the pagan calendar which has never been Christianized. But as we shall see, it is a holiday with two distinct flavors of celebration throughout history…

But first, some nostalgic wanderings…

April 30th, 1972.

Somewhere, I must have learned about May Baskets. I think my favorite third grade teacher mentioned them briefly in Social Studies class (she often talked about holidays and their origins), and then I wanted to find out more about this wacky custom. I was a precocious reader as a kid so it may have been almost anywhere: the Encyclopedia Britannica, Woman’s Day magazine, maybe even Playboy. I don’t recall where, but I know once I learned about the custom of giving them to some one special, I was determined to make one and leave it in secret for my favorite third-grade teacher, Miss V.

I took a small box (about half the size of a shoebox) and glued lavender construction paper to it. I also fashioned a handle out of the same paper, gluing it to both sides. I cut out flower petals shapes in different colors and glued those on, too. Very tasteful, I thought. I cut some daffodils and lilacs from the yard, and put them inside. I had already asked my aunt if she could drive me over to her house, having cleverly looked up her address in the phone book earlier. (Now, these days we would call such behavior something less innocent than childlike admiration; we might call it, oh, stalking). As we drove up with the basket to my teacher’s house, at around 6 pm, I found myself thinking, gee, what if she sees me? I got out of the car, ran on tiptoe (as if that would make me less visible) and put it on her porch. As I turned, the front door opened.

As luck would have it, I was busted: by Miss V. herself! She saw me, then the basket, and figured it out. She smiled and thanked me and said it was very sweet of me. I was mortified that she found me out. But then the next day in school, she made me a card with flowers on it. The front said “Thank you” and the inside said “for delighting my day with a May Basket.” So I got to put that card on my desk like a little teacher’s pet. Of course, I did not think that at the time; at the time I was simply very proud. And realized if I had not gotten “busted” she might never know who brought the May Basket, and I’d have my secret, but only that. This way, maybe the other kids would think of making May Baskets for someone: a teacher, a parent or grandparent. Of course, all I knew was I made something cool and gave it to someone special.

May 1st, 1988

I’m in graduate school. Living in a cool two-bedroom apartment above a funeral home. I have just started really getting into the whole paganism thing. Not in a coven yet, but doing the beginner stuff: practicing a bit of spellcraft, making little altars in my room, going to meetings of the Pagan Students’ Organization, buying books by Margot and Starhawk and Janet and Stewart… So I know it’s Beltane. But not to the extent that I know how to really celebrate it as a true pagan. (Not to worry, within a year or two I would be dancing ’round maypoles, washing my face in the dew and “going a Maying” like a veteran!)

So I get up in the morning and dress in something kinda frilly and festive, not all that atypical for me but I wanted to feel like I was observing the season today. I leave my apartment to go to class, and what do I find on my doorknob but a garland of flowers! Shaped like a crown to be worn. Wow. I don’t even have a clue who it might be from (but I have my suspicions). I take it with me and carry it around to classes that day. I finally run into a male friend of mine who knows I am into this pagan stuff. He apparently knows a thing or two about May Day folklore, and I eventually find out he left it as a sign he was interested in dating me. Which was rather sweet. This was a very shy young man who I cannot imagine actually asking me out on a date. But his leaving a relic of ancient paganism on my door, well, that was impressive. We did date for a while. He was a nice guy and very smart. At the time all I knew was, he made something cool and gave it to me, so he must have thought I was special.

Beltane: a Pre-Christian Fire Festival

“But they are… naked!”

“Well, naturally, it’s far too dangerous to jumo through the fire with your clothes on!”

–Lord Summerisle explaining Beltane to Sergeant Howie in the 1973 film “The Wicker Man”

According to an article entitled “The Merry Month of May” on about.com, “The first day of May is still celebrated as a pre-Christian magical rite in some parts of England. Local people dance around a maypole (an ancient fertility symbol), in what was once one of England’s most important festivals of the year.” May Day and Beltane obviously have much in common, as both celebrate new growth and fertility. Even when May Day celebrations were banned in the late 16th century for being immoral, the customs died hard and it wasn’t long before the festivities were once again widespread. But long before the May Day celebrations, with their maypole dancing, garlands and dances became popular, the ancient fire festival of Beltane took place for centuries.

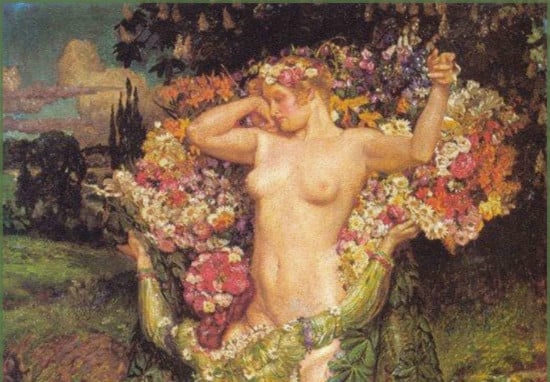

It is not clear where or how the festival of Beltane first came about; Ronald Hutton in The Stations of the Sun mentions the first recorded instance of a bishop in Lincolnshire complaining about local priests who “demeaned themselves by joining games which they call the bringing-in of May” in 1240. May Games were recorded in Scotland in 1432. There is some speculation that Beltane and May Day is related to the ancient Roman festival of Floralia. According to the about.com article, this was “a six-day party in honor of Flora, the goddess of Spring and Flowers, the Floralia was a time of singing, dancing and feasting in the ancient capital.” Dressed in bright colors in imitation of spring flowers, citizens would decorate the entire city with fresh blooms. “Hares and goats, symbols of fertility, would be let loose in gardens as protectors of Flora, and great singing and stomping would be heard in order to wake up Spring.” Of course, dancing is a large part of May Day celebrations as well. Apparently, Flora was also the patron of prostitutes, and during this festival the Roman “working girls” participated enthusiastically, performing naked in theatres and taking part in gladiatorial events. The themes of fertility and sexuality are obviously still very much associated with Beltane and May Day amongst modern pagans… but let’s look more closely at the ancient history of Beltane in the British Isles.

First of all, the origin of the name “Beltane” is disputed. The holiday was also known as “Roodmass” in England and “Walpurgisnacht” in Germany. Alternately spelled Bealtaine, Beltaine, and any number of Gaelic derived-spellings, it is also the Irish word for the month of May, and is said to mean anything from “Bel-fire” Feast of the god Bel” to “bright fire.” Janet and Stewart Farrar, in Eight Sabbats for Witches offer an excellent tracing of the holiday’s Irish roots, and particularly the European fire-god Belenus whom they believe this festival is named for (a name possible traced back to Baal, the bible’s only pagan god, whose name simply means “Lord”). Ronald Hutton states that since the Celtic word “bel” means bright or fortunate, this is adequate to explain the translation as being “lucky fire” or “bright fire.”

For FIRE is what this festival is all about. It is one of the two great fire festivals of the wheel of the year (the other is Samhain). It also falls upon the cross-quarter days, which mark the astrological movement of the sun. In ancient times, the calendar days for these holidays would have been roughly seven to eleven days AFTER we now celebrate them (usually on the first of the month). The way to know for sure is to observe when the sun reaches 15 degrees of the zodiac sign. For Beltane, this is Taurus, the Bull (the sun reaches 15 degrees Taurus on May 5th this year). At Lammas, Leo; at Samhain, Scorpio, and at Imbolc, Aquarius.

Samhain and Beltane divide the year into two distinct halves of great importance to agrarian-based societies (as in western Europe, where our Celtic calendar of eight major seasonal festivals originates). In F. Marian McNeill’s book The Silver Bough, she states: “At Beltane, flocks and herds went to their summer pastures; as Hallowmass (Samhain) they returned to their winter quarters. Beltane may be regarded as a day of Supplication, when a blessing was invoked on hunter and herdsman, on cattle and crops.” Whereas Samhain was a “Day of Thanksgiving, for the safe return of the wanderers and the renewal of the food supply.”

Fire festivals in ancient times were seen as times of propitiation and purification. Propitiation, says McNeill, “means sacrifice; to propitiate the mysterious forces of nature and ensure fertility in field and fold and on the hearth.”

“You’ll simply never understand the true nature of sacrifice.”

–May Morrison to Sergeant Howie, “The Wicker Man”

Human sacrifice was still practiced in Gaul as late as the 1st century BC, and was later replaced by sacrifice of animals (most notably the Bull – another Taurus connection?), and later an offering of specially consecrated cakes or loaves, as in the sun-shaped loaf in “The Wicker Man.” “The life of the fields: John Barleycorn.” But of course, by the film’s end, more than bread was consumed by the flames.

(Never seen The Wicker Man? It’s a cult classic well-loved by pagans for its deliciously politically-incorrect sacrifice of a morally-uptight police sergeant when he visits and island renowned for keeping the “old ways.” The film’s events take place on the days leading up to Beltane.)

As for purification, fire has always been seen as its chief agent. Traditionally, all domestic fires in Irish, English and Scottish households were extinguished on Beltane Eve, after having been kept lit continuously all year. Just before dawn, villagers would process with their animals up the hillsides to the highest point where fires would be kindled and relit for people to see for miles around. It was also traditional to build these fires out of nine of the sacred woods from Druidic folklore, including oak, ash, thorn, rowan, apple, birch, alder, maple, elm, gorse, holly, hawthorn, and others.

The bonfires were lit so that a narrow passage existed between two fire, so that cattle and other livestock could be led between the fires, to purify them from disease or sterility for the coming year. Torches of dried sedge, gorse or heather were also lit and carried around remaining flocks or stables, to further purify the air.

Fire, Water…

Water, the other element of purification, also plays a strong role in Beltane custom. Spring was the traditional season of “well dressing” particularly in Ireland where wells were seen as holy places (even with the advent of Christianity, when many wells dedicated to pagan goddesses were re-dedicated to the Virgin Mary). But even more specific to Beltane, morning dew was seen as sacred and magical. To this day, young women all over the British Isles rise at dawn to wash their faces in dew (dew from oak and rowan trees is said to be particularly well-suited). It was and is believed doing so would enhance a woman’s beauty and health in the coming year, and if she uttered an appropriate charm while doing it, she might also meet her future husband in the coming year.

This poem was written by someone who observed young women engaging in this practice in King’s Park in Edinburgh:

“On May Day in a fairy ring,

We’ve seen them round St. Anton’s spring,

Frae (from) grass the caller dew-drops wring,

To weet their een (to wet their eyes)

And water clean as crystal spring

To synd them clean.”

Village elders also left libations and offerings of food to guard their flocks against any evil from the fairy folk, or from the ravages of storms, floods, or disease. Butter, eggs, milk and cheese were left in hollow stones, or poured into the ground. Alternately, ale or fresh-baked bread was offered, with the idea that a gift of the finest the household could provide was the most suitable offering.

In Aberdeenshire, McNeill tells of a custom of kindling fires on May 2nd, as it was believed “witches were abroad then.” Beltane, like Samhain, was the time when the veils between the worlds were thinnest, and like fairy folk, “witches” were thought to be fond of this time and to use it for magical rites. Keep in mind, in those days, the “witches” were the ones that country folk worked magic against, and those of us today who call ourselves “witches” are actually closer in spirit to those village wise women and cunningmen, who used folk magic and spells to protect their homes and families and flocks. The Aberdeenshire citizens believed witches would steal milk from cows, and ride stolen horses to their meetings. Fires were lit and villagers would hold hands and dance around them three times deosil (sunwise) – does this sound familiar? Except they would then yell out “Fire! Blaze and Burn the witches! Fire, Fire! Burn the witches!” Thanks goodness we have moved far beyond these, ahem, heathen customs!

Earth and Air…

Dancing was a common way to celebrate the season. The Maypole rites being an obvious example, but before this practice became widespread, dancing without benefit of a giant pole was also common. Dancing round the bonfires was seen as a way to partake of the purification of its flames. Women wanting to get pregnant would perform fertility dances at the fireside. Once the Beltane fires were relit on the hillsides, villagers would carry a flaming torch, the “need-fire, ” back to their homes and relight their hearthfires with it. On the way, it was customary to dance and sing the season in. Records of may dances and songs go back to well before the 16th century. The songs affirmed the purpose of the fire ceremonies: protection and purification. The protective power of the magical woods was thought to affect any who lit their households with their flames. The sight of the bright flames on the hills, and the line of people processing with torches in the dark, must have been an awesome sight to behold.

(This year in Ireland, a huge ritual will be held to re-kindle the ancient fires of Beltane. It was nearly cancelled due to foot and mouth disease, but now it looks like this ancient ritual of healing the land and its creatures will take place after all, and not a moment too soon.)

The most protective wood of all was rowan, and prior to the Beltane Eve bonfire lighting, branches of rowan were cut in huge amounts and used to decorate the homes of all. Branches tied with red thread (signifying the rowan berries, and a favorite color of fairies) were hung in doorways of homes, stables, barns and sheepfolds, and, as McNeill states, particularly “in the midden, which was a favourite of the black sisterhood.” (I think she meant witches.) In the Highlands of Scotland, girls tied sprigs of rowan in their hair or on their clothing just after washing in may dew. (Incidentally, in “The Wicker Man” the hapless Sergeant Howie is first sent for to investigate a missing girl, whom he believes intended for human sacrifice: her name is Rowan.)

Just as rowan branches were seen as protective, people also gathered armsful of tree branches in blossom to decorate their homes in honor of the arrival of spring. This custom was usually fulfilled the following day, on Beltane proper, after the midday sun brought the blossoms to the fullest size and fragrance. In later years, when May festivities spread to England, these branches were carried from door to door, offered with songs, in the expectation that gifts of sweets, money or food and drink would be offered. This in turn led to the “garlanding” customs popular in southern England, once the province of women but later an activity popular for young girls and sanctioned by local schools and parishes. No matter what the blossom, it was known as “gathering the May.” Hawthorn was most common, and so one of its folk names is “May.” (Rowan Morrison’s mother’s name is May, as well). “Going a Maying” innocently refers to the custom of young people gathering blossoming tree branches; but later became a common euphemism for what happened after the branches were gathered in the woods, and before they were brought home.

Once the fires were relit on Beltane Eve, and children put to bed, and the wee hours of Beltane morning arrived, the more adult festivities began. And that includes the traditional activities associated with fertility (remember Flora and her fondness for prostitutes? Kinda along those lines). Newly wed couples and new brides were expected to perform fertility rites around the bonfires, to take advantage of their potency and purification. Humans were much more closely connected with the rhythms of the earth in those days, to put it mildly, and no doubt the running of sap in trees, the blossoms and buds bursting forth, the scents of flowers and new growth and damp soil and rain, all stirred the senses and reawakened the body—these days we call it “spring fever, ” but in antiquity, indulging such urges was completely normal and expected.

Or, in the words of Lerner and Lowe, from the musical “Camelot”:

“It’s May! It’s May!

The lusty month of May!…

Those dreary vows that ev’ryone takes,

Ev’ryone breaks.

Ev’ryone makes divine mistakes!

The lusty month of May! “

Naturally enough, unwed men and women would also partake of the spirit of these rites, and find themselves venturing off into the nearby fields or forest to perform their own fertility rites. Blessed by the gods on this sacred night, such unions were seen as wholly proper, even when not blessed by marriage; they were referred to as “greenwood marriages.” It is also true that betrothed couples would make love at Beltane, and if the union did not prove fruitful, i.e. no pregnancy resulted, they might dissolve the partnership before marriage without repercussion. In fact, the origin of the “year and a day” handfasting custom observed by modern pagans, in which they renew their vows after one year, dates back to this. If new marriages did not produce children within one year, couple often split and married others, with no penalty.

But why sex? If the point of these festivals was to preserve the land and the flocks, why not simply observe fertility in the birth of lambs, the growth of plants? Ah, but ancient peoples believed in sympathetic magic: that practice of a small, symbolic action representing a larger one. By making love in the fields, human beings believed they were helping make the earth more fertile, blessing it with their own activity of producing new life and abundance. And even if the ultimate goal of such unions was not pregnancy, it couldn’t hurt to help the magic along!

Which brings me to what is often considered a wholly sexual symbol, and main feature of ancient May Day and modern Beltane celebrations: the maypole.

Phallic Symbol? Or Tree Worship?

Beltane celebrations in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, the Isle of Man and parts of Britain later became intertwined with May Day rites derived from the Floralia (due to the Roman invasion of Britain, mostly). But more importantly, the different customs associated with May 1st became very diverse and widespread to such an extent that these practices were banned on a wide scale. Though complaints about “immoral” practices started early on (as in the 1240 reference from Hutton), the Protestant, well, protest against May rites came to a head in 1555, when May Day observances were banished by Parliament. This mainly had to do with the “Maying” rites, which uptight clergy believed were merely opportunities for fornication in the fields and defiling of young women (mistakenly believed to come away pregnant more often than not. Hutton notes that later demographic research showed no concomitant rise in pregnancy rates at this time of year; in fact, late summer was a much more common time for conception).

By 1565, the common practice of electing “an Abbott of Misrule” and other ritual roles, like Robin Hood, Maid Marian and others, was also banned by law. Such plays had become commonplace, as had Morris dancing, sword dances and other celebratory ways of “dancing in” spring. Margaret Murray, in “The God of the Witches” noted the similarity between Robin and his typical band of 12 men being modeled on a “Grandmaster and his coven.” Although it is just as clearly related to Jesus and his disciples. In any case, the traditional green costumes and elaborate dances, as well as Robin Hood’s association with Robin Goodfellow, or Puck, were also connected to fairy tradition and so seen as “heathen” by the clergy. Some have speculated that this tradition of using Robin and Marian as May Day “deities” actually has its origin in Diana and Herne: goddess of the hunt and forest creatures, and god of the wild hunt. Indeed, Herne is seen as one aspect of the Green man, and many May Day rites also featured The Green Man. Diana is also a predecessor of the Queen of the May, a role later usurped by Marian… but Diana’s virgin aspect makes her a likely model for such a role.

The maypole itself was banned in 1644. By 1660, when it became clear the monarchy would be restored, May Day rites were once again permitted and in fact spontaneously reappeared across the country. But by then the holiday had lost much of its earlier sexual significance; May Day had replaced Beltane, if you will. But it is also true that by this time, the dancing of the Maypole had become the central “ritual” of this holiday, not the bonfires. Only in remote parts of Ireland and Scotland did the fires apparently continue as the dominant feature.

It is not clear when the maypole first became part of the May festivities, or what its exact origin is. Our post-Freudian society naturally wishes to call it a “phallic symbol” and have done with it, and indeed this seems fitting. A wonderful scene in the oft-mentioned “The Wicker Man” finds the young male students dancing round the maypole, while the female students watch them from their classroom, in which they listen to a lecture about the rites and rituals of May Day (even their textbooks have a chapter on it!), and all the girls in unison know the answer to what the maypole represents: “phallic symbol.” The teacher, Miss Rose, says it is the penis, “revered in religions, such as ours, as the generative force in nature.”

But according to Ron Hutton, other explanations present themselves. Some authors, including Sir J.G. Frazer in The Golden Bough, refer to it as “the repository of a fertility-giving tree spirit.” Many years earlier, Thomas Hobbes suggested the maypole was meant to honor the Roman god of male potency, Priapus. Hutton himself suggests they are just as likely symbols of tree worship (particularly since the earliest maypoles were living trees, stripped of all leaves but for a tuft of greenery at the top). He also mentions the Northern European concept of the divine tree which connects the earth tot he world of the divine, and the maypole as a connection between them. Finally, he credits Mircea Eliade for his theory that it is “merely a way of rejoicing at the returning strength of vegetation.”

Modern Traditions

“For the May Day is the great day,

Sung along the old straight track.

And those who ancient lines did ley

Will heed this song that calls them back…

Pass the cup, and pass the Lady,

And pass the plate to all who hunger,

Pass the wit of ancient wisdom,

Pass the cup of crimson wonder.”

Jethro Tull, “Cup of Wonder, ” from the 1977 album Songs From the Wood

Modern pagans celebrate Beltane as a festival of reawakening spring, of fertility, of the renewal of the lifeforce, of creativity, or rebirth, of love and sexuality, or birth and regeneration. Janet and Stewart Farrar, whose work forms the basis for many Wiccan groups, offer a ritual for Beltane in their Eight Sabbats for Witches in which they feature the Oak King as a symbol of the death of the old season, and a “bel-fire” is rekindled to usher in the new season, along with lyrics from Rudyard Kipling’s famous song of tree worship in England, “Oak and Ash and Thorn.”

“Oh do not tell the priest our plight, for he would call it a sin,

But we’ve been out in the woods all night a-conjuring summer in;

And we bring good news by word of mouth, for women and cattle and corn,

For now is the sun come up from the South by Oak and Ash and Thorn.”

Some covens kindle their own bonfire, using nine of the sacred woods. Others celebrate the Great Rite, the sacred marriage of the god and goddess, in symbolic or actual fashion according to their tradition. Solitary practitioners often choose Beltane as a time to reaffirm their dedication to the path; and couples in a magical partnership might choose this auspicious time to work sex magick, to achieve a chosen goal.

Larger pagan gatherings feature maypole dancing; I have attended a number of these over the years and there really is nothing like a fifty-foot tall maypole with a hundred people dancing around it with ribbons!

May wine is a traditional drink of the season: to make your own, simply add dried or fresh meadowsweet to white wine. Let it steep for at least 24 hours. You can either leave the herb in the wine or strain it out. The herby, vanilla-like fragrance and taste are indescribable, and really say “Beltane!” I have also seen recipes for “May Cup” on the net. And this is a fine time to experiment with aphrodisiac brews, for example adding damiana to some white zinfandel.

Perhaps it is best to remember this as the time when Aphrodite, who rules the sign of Taurus, is coming into her own. She presides over the realms of love and sex and beauty, but also over the flowers and fruits which brig us such pleasure: delighting our senses with their colors and scents and tastes and juices. She fills blossoms with nectar, and her body is beneath us as we walk and dance upon the newly-yielding, softened earth, alive again after the dormancy of winter, full of new life. She is in the animals, the lambs born at Imbolc who frolic among spring meadow flowers, the other creatures who come into their mating seasons at this time. And she is in us, offering her discernment of beauty, blessing our eyes with new awareness of color and texture in nature. In our hearts which beat quicker with the warmth of the sun and the fires rekindled within us. In our minds, alive to possibility and creativity, awakened and reborn with new energy. And in our bodies, walking on hills and in meadows and forests, dancing around our own fires and in circles with like-minded loved ones, sharing laughter and song and love, enjoying and creating the feast, the celebration, the magical birthright that is life on Earth.

May your fires burn bright!

(This article first appeared on The Witches’ Voice website in 2001.)