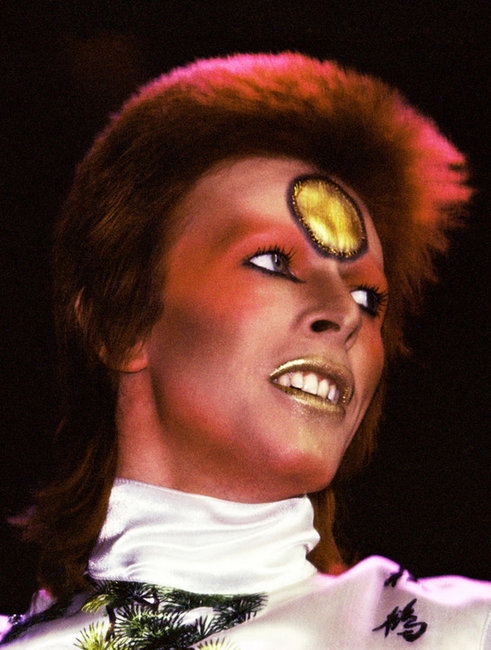

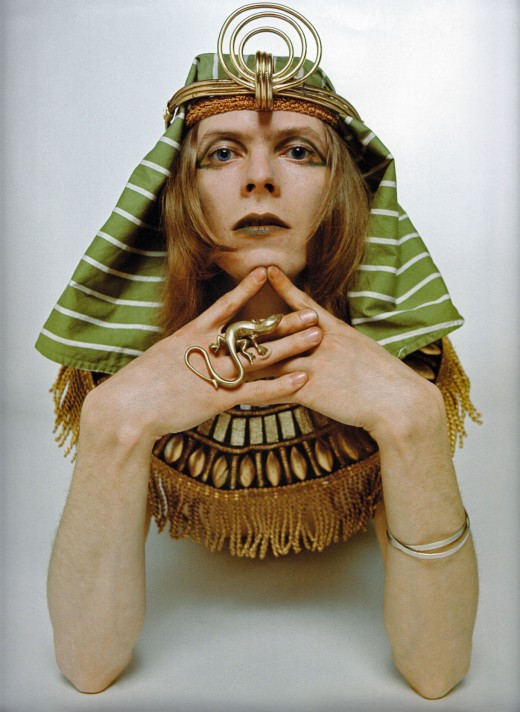

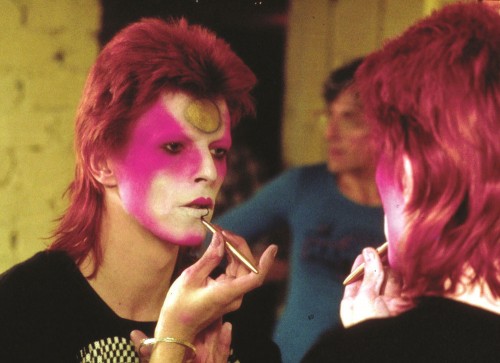

It’s stunning to behold the widespread grief and admiration being expressed across social media today, as millions learn of the death of one of popular music’s most beloved icons. David Bowie was a shape-shifter of the highest order, creating unusual and glamorous personae decades before theatrical costumes became the norm in popular music. Bowie was making music videos in 1969, before anyone had a name for the art form. He wrote entire concept albums based upon the stories of his flamboyant, often troubled, characters: Ziggy Stardust (whose third eye made him a mystic), Aladdin Sane (his lightning bolt echoed in Harry Potter’s wizard birthmark), The Thin White Duke, and others.

The occult and magical imagery in his music, as well as his frequent mention of spirituality (although he has often been thought to be an atheist), made his music particularly meaningful and perhaps even formative to people who identify as pagan. But more significant than the power, wisdom and strangeness of his lyrics, Bowie personified a misfit of otherworldly dimension. Before he became popular worldwide in the 1970s, his strange songs and unusual mode of dress, not to mention his fluid approach to gender expression, made increasingly large waves in the worlds of fashion and performance.

Despite being somewhat shy as a performer, Bowie found a way to invent identities that communicated powerfully. What some of us call “magical identity” can be seen writ large in Bowie’s creations: glittering, androgynous, bold, godlike.

David Bowie’s influence upon young people who felt different, sexually confused, or merely oppressed by a society that shut down their creativity, cannot be measured. Songs like “Changes” and “Oh! You Pretty Things” were anthems to adolescent empowerment. “It’s a godawful small affair to the girl with the mousy hair” he sang in “Life on Mars,” a song whose gender-bending video is brilliantly recreated on American Horror Story: Freakshow by Jessica Lange in turquoise drag. His words could make even the most alienated teenager feel welcome in the world: “You’re not alone. Give me your hands. You’re wonderful.”

In later years, his film roles added to this assortment of characters. He was an extra-terrestrial who finds love on earth, a cruel but charismatic goblin king, and a vampire who never wanted to die. His rise to fame is explored in the fictionalized biopic Velvet Goldmine (1998), with a Bowie-like rock star being portrayed by the glamorous, animal-sexy Jonathan Rhys-Myers. In The Runaways (2010), we see young rock-starlet-to-be Cherie Currie dressing in a white jumpsuit and Aladdin Sane makeup for her junior high talent show. And in 1996’s Basquiat, we see David Bowie portray art world icon Andy Warhol, who was the subject of a song on his break-out album Hunky Dory in 1971. As with many performers thrust into the spotlight, Bowie dealt with his share of occupational demons, including drug abuse, relationship problems and mental exhaustion.

In his book Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll (this was published in 2015 and I have been slowly devouring it, the way you savor really good chocolate; expect a longer review soon), author Peter Bebergal explores the roots of occult belief and practice among rock artists such as The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and David Bowie. Bebergal’s own life was deeply affected by his love of music, and the presence of occult ideas and symbolism in rock music attracted his attention at a young age. His book is not only an intelligent overview of the occult’s presence in rock and roll, but a personal examination of the often indescribable emotional and intellectual impact of the attendant ideas and imagery. In Bowie’s case, the artist’s engagement goes beyond surface trappings or sensationalism to full-on magical workings.

As Bebergal explains in this interview extract, Bowie was a rare exception to this trend who had an actual personal involvement with occult and esoteric beliefs, the Kabbalah in particular:

How deep was David Bowie’s interest in the occult? On one hand, he tended to flit from one subject to the next in the 70s but on the other he seems to have been quite well read.

PB: As I say in the book, I believe David Bowie is true magician in the story of rock & roll, the artist who most perfectly realised the definition of magic, both Crowley’s original (“The science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with Will”) and Dion Fortune’s modification (“Magick is the art of causing changes in consciousness in conformity with the Will”). The thing I wanted to emphasize in Season Of The Witch is that the occult imagination is not simply about belief or practice, it’s about how the application of the occult became the very method by which rock & roll was often realised. Bowie’s music and performance were a magical practice, maybe even more potent than if he sat by himself in his room and tried to conjure a demon. I think this goes to the heart of my frustration with the occult merely as a belief system. Without art, without some expression of those experiences and those interactions with the unconscious, I lose interest. It’s fun to imagine Crowley at the Boleskine house trying to meet his Holy Guardian Angel, but what is left except the story? The story of David Bowie drawing the Kabbalistic tree of life in the studio when he was recording Station To Station resonates because of Station To Station the album. It’s a masterpiece, and it is partly a result of what was going on in his head as he tried to manage a psyche fractured by cocaine and occultism.

As Bebergal mentions, Station to Station was an album made during a trying time in Bowie’s life; it was 1975 and his meteoric rise to stardom was at a pinnacle. He had moved to America from England and was frequently seen performing on American television. (I recall seeing him on TV one night and thinking, “Wow, that guy is weird. Cool jacket, though.”) As Bebergal mentions, he was addicted to cocaine,* and in his sleeplessness and seemingly-boundless energy, as well as his self-imposed isolation, Bowie immersed himself in books, many of them occult-related: books by Aleister Crowley, Dion Fortune (Psychic Self-Defense, in particular), and writings on numerology, the tarot, UFO’s and secret societies.**

In recent years, Bowie’s public performance and recordings became more infrequent. But just three days ago on his 69th birthday, the release of what would become his final album, recorded with jazz quartet, was met with critical acclaim and fan excitement. A complete departure from his earlier music stylings (which ranged from folk to funk to rock to pop), it nevertheless has a quintessential Bowie sound. It has no official title: the symbol of a black five pointed star has led marketers and critics to refer to it as “Blackstar.” It is said that David Bowie created this last artistic work knowing death was imminent.

The stunning video of the song “Blackstar” contains many occult images including crows, candles, scythes, skulls and Bowie holding aloft a book with a black pentagram on the cover. The lyrics are somewhat inscrutable but the theme of death is throughout:

Something happened on the day he died

Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside

Somebody else took his place, and bravely cried

(I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar)How many times does an angel fall?

How many people lie instead of talking tall?

He trod on sacred ground, he cried loud into the crowd

It is impossible to imagine what music would have been without this man’s bold and brilliant vision, his unique talent, his courage. His influence cannot be exaggerated.

Many times today I have been thinking of one of my favorite Bowie songs, “Quicksand” from my favorite Bowie album Hunky Dory. It begins:

“I’m closer to the Golden Dawn

Immersed in Crowley’s uniform

Of imagery”

and ends:

“Don’t believe in yourself , don’t deceive with belief

Knowledge comes with death’s release.”

* * * * * * * *

*This article details Bowie’s drug addiction and its connection to his occult interests

**An interesting in-depth article on this album and Bowie’s engagement with the occult can be found here.