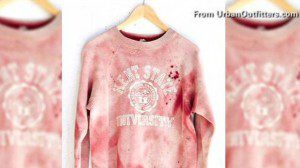

With many others, I was shocked to see the release of a Kent State sweatshirt by Urban Outfitters spattered in fake blood. The image is to the left; though many of us are accustomed to seeing blood to some degree, this article of clothing as captured in a screenshot is nonetheless unsettling.

With many others, I was shocked to see the release of a Kent State sweatshirt by Urban Outfitters spattered in fake blood. The image is to the left; though many of us are accustomed to seeing blood to some degree, this article of clothing as captured in a screenshot is nonetheless unsettling.

Here’s what Urban Outfitters said in response to the outcry this item of clothing stirred up:

“It was never our intention to allude to the tragic events that took place… and we are extremely saddened that this item was perceived as such. The one-of-a-kind item was purchased as part of our sun-faded vintage collection. There is no blood on this shirt nor has this item been altered in any way.”

In their statement, Kent State University officials said the following: “We take great offense to a company using our pain for their publicity and profit. This item is beyond poor taste and trivializes a loss of life that still hurts the Kent State community today.” The loss of life mentioned refers to the death of four students on May 4, 1970 at an anti-Vietnam War protest. I actually walked the Kent State campus several years ago, and in a moving moment saw the spot where the students died.

Here’s my own hunch: there is more at play here than simply bad judgment on the part of Urban Outfitters. Specifically, we’re witnessing an example of a broader trend related to aesthetics, morality, and truth. To simplify, art and design have been influenced in at least some sectors by an amoral mindset grounded in a post-modern, anti-foundationalist worldview.

The classical Christian approach to culture-making was conditioned by the quest for the good, true, and beautiful, a pursuit affirmed by Augustine, Aquinas, and non-Christian philosophers like Plato. Though this triadic ideal can be somewhat hard to define when actually creating art, it proved hugely influential over many centuries, including the Renaissance and Reformation periods. If we zip ahead to our own day, however, the Western artistic community has been profoundly influenced by an amoral viewpoint. Art is now seen by many artists as a matter of aesthetics, of non-foundationalist beauty that has no standard and is not connected to transcendent truth and goodness.

What does this mean in practice? It means that art and design no longer need to reflect or embody traditional morality. Art as practiced by at least some (by no means all!) Western artists is calculated to shock, to unsettle, and to push the viewer past accepted ethical boundaries. In such practice, violence and sex are aestheticized. This is the critical turn.

One thinks, for example, of the way Quentin Tarantino employs stomach-roiling violence in his films, creating scenes that are graphic and do not need to be. When it comes to sex, one could point to show after show, movie after movie, which renders sex an aesthetic event, presenting it as an amoral happening that viewers may freely watch without moral qualms. Even when filmmakers or TV show creators present violence and sex as part of, say, a general arc of personal destruction, we must be clear in our own minds that they have not succeeded in creating value-neutral art. It is not good to enjoy gratuitous violence; it is not good to enjoy sex and nudity outside of the confines of marriage.

I’m thankful that Christian discussion of the arts now considers matters aside from a “swear word count,” for example. But I wonder if the church is being influenced to some degree by the amoral aestheticism of a secular culture. Would we watch a pornography film that included a powerful scene of personal redemption, or because it explored the depths of human depravity? If the answer is no–and I surely hope it is for believers–why would we watch media that may not be classified as pornography (of either a sexual or violent nature) but is to a considerable degree akin to it?

Of course, our engagement with art and design is not only moral. We do not only count the swear words in a movie before deciding to watch it. But if our engagement is not solely moral, we need to make clear that if it is truly Christian, it must also be morally informed. We cannot approach movies or TV shows or art exhibits or even, strangely, Urban Outfitters sweatshirts as if morality conditioned by the revealed mind of God does not exist. It surely does, and this revelation bears on and influences our interaction with the arts, high or low.

To bring this to a conclusion: I don’t think fellow Christians would approve of the item of clothing in question. That is not the point of my little reflection. My point is that this particular episode shows us that an amoral approach to art and design, one that treats even human tragedies in purely aesthetic terms, clashes with the human conscience. We instinctually know, whether Christian or not, that it would be wrong to sell a line of concentration-camp-like pajamas. There might be elements of our society that would applaud such a bold and outre move. Christians, with other people of conscience, will surely recognize that we cannot aestheticize or render amoral that which is tragic and wrong.

Such an instinct does not leave us a smoldering schoolmarm or a “fundamentalist”; it is profoundly theocentric. It is part of setting our minds on things above (Colossians 3:1-11). This is not easy in a fallen world–but it is our Christ-exalting, joy-fueled calling as believers.