A few weeks ago, our Dominican-run Adult Sunday School tackled the topic of “Deadly Sins and Lively Virtues” and the brother teaching walked us through St. Thomas Aquinas’s classification of sins and their progeny (i.e. clamor (speaking so intemperately so as to lose the ability to say actual words) is one of the offspring of wrath). As our Dominican friar kept expanding the flow chart of faults, the most surprising branch turned out to be the cluster of sins rooted in Sloth.

(Editorial note: all errors here about Aquinas are the result of me trying to summarize a one-hour class a week after the fact, not a fault of my Dominican instructor)

It’s common to think of sloth as simple laziness — hitting snooze on an alarm, leaving late for an event, etc. But, if that were all that sloth was, everything about St. Thomas Aquinas’s classification system is odd. He pairs Sloth with Vainglory because both are about the kind of disordered loves we can have in isolation. In Vainglory, we prize ourselves too highly, luxuriating in our own excellence without regard for anyone else’s (this is different from envy). In Sloth, we prize the world too little, sinking not into mere passivity but into “sorrow for spiritual good as a divine good.”

That sounds a little abstract, so I’ll expand a bit (drawing on our class’s handout). When a person starts to feel sorrowful over divine goods, they might try to avoid the cause of their sorrow by actively shutting out awareness of the good-as-good, which leads to despair.

Or they might endorse the good in theory, but shirk any activity (prayer, community, reading, etc) that would draw them closer to the good and then they wind up sinking into faintheartedness, sluggishness, and spite (i.e. spiting the spiritual authories above them or, in non-monkish cases, just friends and family, who are trying to help).

A person in the grips of sloth might go beyond simply avoiding the spiritual good that pains them and begin actively despising it (malice). Finally, instead of quietly retreating from the good or actively fighting it, a person might seek out distraction, turning to any other source of pleasure to somehow replace what they are lacking (wandering of the mind).

Our Dominican teacher told us that a great deal of the theology of sloth (also referred to as acedia, which means something like sorrow/grieving) is drawn from the experiences of the hermetic tradition, where monks struggled to keep their spiritual bearings when they went to live alone in the desert or on top of stone platforms or what have you.

Because of the perils of acedia, no one under a spiritual director was allowed to just begin as a hermit, even if they had a calling to that life, because it was necessary to first live in community in order to build up the strength and discipline to live on your own.

Today, though, what was perilous for monks is commonplace for twentysomethings. Young adults are urged on to independence as a path to maturity, instead of the lifestyle for which maturity is a prerequisite. We live or work in semi-seclusion and, per Nisbet, are community poor.

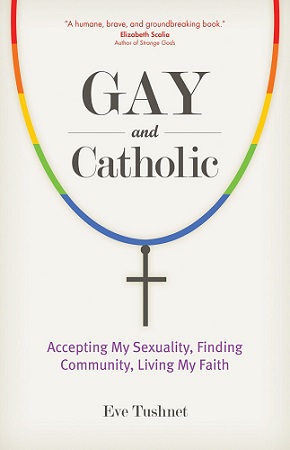

So, how does this bring us back around to Eve Tushnet’s Gay and Catholic: Accepting My Sexuality, Finding Community, Living My Faith?

Eve’s book isn’t about the what or why of Catholic teaching on queer relationships. She’s writing about how queer Catholics like her can discern and live out vocations to love and self-gift outside of marriage (and how the people in their lives can support and love them). It’s a great book, with plenty of points that are tailored specifically to gay people, but I think it has a broader relevance, too.

Queer Catholics who follow church teaching expect to not get married. And, because our culture sees marriage/family as the primary way to care for another person, people like Eve know that, if they want to live vocations of love, a lot of the time, they’ll have to build them themselves.

Plenty of other people may find themselves in similar situations, either for their whole lives or just for a season of their lives, but, because singleness may feel like happenstance, rather than a mandate, it’s easy to just wait for it to pass, rather than work to find ways to serve others and welcome the love and service they may wish to offer you, even if it comes in unexpected forms.

Eve discusses a lot of models of vocations to love outside of marriage or monkhood (including vowed friendship, living in intentional communities, living with family, choosing work with an eye to whom you serve, etc). She also prepares the reader to discern their own path, by talking about how to choose the “next right thing” to do, especially when your friends, family, and faith community may feel that you’re in uncharted waters.

In many sections, Eve’s book seems to be about developing fruitful dependence on others (and allowing others to need you). In one of my favorite bonus book extras that she wrote (“Self-Abboting: Sin or Vice?”). The post is short, and I recommend just popping over to read it, but here’s a representative passage:

One reason I’m so high on the idea of people living with their parents/families of origin, or in a family household, is that it allows laypeople to be one another’s abbots, to guide and watch over one another. It requires adherence to rules, sometimes-sacrificial consideration of others’ needs, and a surrender of one’s own comfort, preferences, and autonomy. Intentional community living, which gets a nice chapter in the book, is another way to attain some of the spiritual benefits of monastic life.

The desert monks, living an ascetic existence, are our guide to sloth/acedia because, less distracted by other, more worldly sins, they were able to give it a clear-eyed examination and instruct us in how to fight it.

Eve’s book is similarly helpful — because she has head-on confronted a problem most of us (hope) we are only hitting glancingly, she has grappled with the ways our culture’s defaults and scripts can isolate and shrink us.

Her book is a resistance manual for everyone who notices they’ve been drafted into a culture war. Not us-against-them, but all of us versus the temptation to express love faint-heartedly, slothfully, along the path of least resistance that our culture affords us.