Our courtship is slightly famous. Bruce gives his students copies of the essay he wrote about it, and I have my students read it as well. And then, to boldly move it into the public blogosphere, Rosalynde Welch wrote about it here.

Our courtship is slightly famous. Bruce gives his students copies of the essay he wrote about it, and I have my students read it as well. And then, to boldly move it into the public blogosphere, Rosalynde Welch wrote about it here.

The truth is, Bruce had been assigned by his friend Phil Barlow to write the essay for a book, but he hadn’t finished it by the 1984 deadline. Actually, he hadn’t started it–though he had good ideas. He thought he’d write about faith and love. But how do you do that when you’re a single, 33-year-old English professor who knows about love mostly from Edmund Spenser’s poetry and Shakespeare’s plays?

There was another stressful complication. Not only was Bruce unattached, but he was under considerable pressure to find a wife. The perception was that he wouldn’t pass his third-year (continuing status) review if he were single. In fact, our department Chair had sent him a birthday card in November: “Please get married! We want to keep you!”

It felt to Bruce as though he had been told that he could keep his wonderful job–if he would first simply go to the moon.

And then, there I was, standing at his door and saying, “Hi. Wanna go to the moon?”

No, it wasn’t quite that easy.

I was already in his class, a soul-bruised divorcee trying to adjust to her own single status and to deal with a legion of new insecurities. Primarily, I thought I was torturously ugly. This perception had been enhanced by my previous husband’s frequent statements that I was, in fact, “hideous looking.” (Don’t be too hard on him. He had his own issues.) My failure to be beautiful was attributable to one thing, which is true to this day: I am a redhead. A real one. Most real redheads have invisible eyelashes and eyebrows. Our eyes look naked without mascara.

I recall an event in my teens: my post-surgery, drugged-up reaction to seeing a bottle attached to my stomach, gathering bile from my liver. I had just had my gall bladder removed. I looked at the bottle, saw that it was now connected to me and thought, “Well. I’ve grown a bottle. I guess I can live with that. Only… what do I do when I get married? Maybe I can get a fancy lace purse and put it in that. Yeah, that’ll work. What about my wedding night?”

That foggy moment was equaled by the very real fear that my husband, whoever he was, would see me without makeup and would bolt. Indeed, when I revealed my unadorned eyes to my first husband, my fears were realized.

So, in 1984 as I sat in the front row of Professor Young’s literary criticism class, I wore false eyelashes. I wanted no hint of what I really looked like. I was terrified that I would fail his class (which was absurdly difficult) just as I had failed in my marriage. My insecurities made me overeager to participate, sometimes frantic, desperate to please. This is how he describes me (back then) in his essay: “The judgments I made mostly tended in the direction of seeing her as “not my type”: bright, yes, even brilliant; but also too high-strung, confusing, leapingly intuitive.”

Also (something he didn’t know) subject to sudden teariness and to pinching her eyelashes to be sure they were still attached.

So there we were–a divorcee and a bachelor, student and professor, talking about Plotinus and Matthew Arnold.

There was one evening, however, when I was studying handouts outside of his office, and he was there. We started talking like actual people. He told me about his sister who had M.S. I wanted to ask him to go to a movie with me. Just as I was about to, he said he had a meeting.

On the last day of class, he was racing through all of the material he hadn’t quite covered (roughly 1/8 of the entire course) and I was trying to slurp it in. I raised my hand and asked a question to get clarity. He answered brusquely. A few minutes later, I raised my hand again. This time, he looked at the clock, and then looked at me, glaring. “What’s your question, Margaret?” My mind blanked, and–oh yes–those tears started rising. I wondered if I should leave. I was at risk of breaking into sobs at any moment. I could not bear a glare and its message. He continued looking at me with accusing impatience. “I forgot,” I said. I lowered my head as he continued the lecture. I took notes on every word, fearful that if I looked up, I’d fall apart.

He knew he had been too abrupt. After class, as I was rushing to a bathroom where I could let the tears fall, he touched my elbow and said, “I’m sorry.” I gave him a huge fake smile and answered, “Oh, don’t worry about it.” Then I dashed to a bathroom, closed the stall door, and wept.

Not much of a beginning. And yet, there was something about him which drew me in. I heard him lecture about peace making and I recognized that he was a genuinely good man. I read his master’s thesis on George Herbert and loved the depth of his thoughts. I saw the way he treated my daughter and realized he was gentle.

I got an A- in the class.

Two weeks after it ended, Bruce Young and I went on our first date, to see It’s A Wonderful Life–hosted by Jimmy Stewart in person. (He had just donated his papers to the BYU library.) I held Bruce’s hand and he let out a small gasp.

We got engaged in March. At the English Department awards ceremony, I received a writing award. Bruce and I also quietly announced our engagement. One of my writing professors, Doug Thayer, congratulated me. I assumed it was on my engagement and said, “You already knew, didn’t you?” “Oh course,” he answered. “I made up the list.” I gave him a look and he considered things momentarily. “Wait a minute. You’re not talking about the writing contest, are you. Is there something else? Are you and Bruce engaged?”

The dean, Richard Cracroft, was far more exuberant. “Margaret,” he gushed, “what a sacrifice you’re making! How can we thank you? We love Bruce. We’re so grateful to you.”

Soon, of course, the excitement faded and Bruce and I were left as we were–two very insecure people. And he still hadn’t seen my naked eyes. What would he do when he saw them?

We talked about it. I admitted my fear. His response was easy: “Go wash you face.”

Oh that cruel gift of imagination! The gift that had let me create stories and novels had a sharp side. I pictured Bruce seeing me with my naked eyes, looking quickly away, trying to be kind, then shaking his head and whispering, “I’m sorry. I didn’t realize…”

I came to him, the wash rag still covering my face. “All right,” he said. “Let me see.”

I removed it slowly.

He drew his face to mine, examined each eye, and said, “You are so beautiful. I like you better without the make up.” I embraced him.

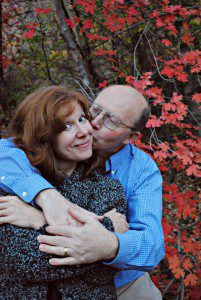

We began our journey on May 17th, 1985.

Now, Phil Barlow wants an addendum to the essay. I’m not sure Bruce has finished it. So I’ll add my own.

It was a hard first year, but we gradually settled into each other. And that’s how we end each night–settled into each other; my head on his stomach, his arm on my back, my right leg crossed between his legs. We watch an episode of The West Wing, and then each of us turns over, I facing right and Bruce facing left. “I love you,” I say. “I love you too, ” he answers.

We have raised our four children. Bruce has taught my classes when I’ve been on a trip discussing race issues. I’ve taught his when he’s gone to a Shakespeare conference. We have tended to use literary figures when we’ve fought–the worst coming from me during our first year of marriage. “You–you’re like Uriah Heep!” I accused him. It was a cut to the core. “Uriah Heep,” he said after an astonished moment, “is a dispicable person! How could you say that?”

We have survived the deaths of two of his sisters–one to M.S., the other to breast cancer. I held him so he wouldn’t fall when the casket was closed over his baby sister’s body. He held me when I woke up sobbing the day after my best friend was killed in a car accident. We have survived the deaths of his parents, and are now serving my father while his health declines. We have been stretched by unexpected turns and our children’s choices, by our jobs, our many projects, our church callings, and by our travels. We are now senior faculty at BYU, and our former students are replacing us. Bruce is a bishop, and I am a strong woman–confident and recovered from the slings and arrows which once caught me.

What Bruce finished writing soon after our marriage is still true:

I continue to see, as I experience married life, how easy it is–through laziness or fear–to resist whatever my own mind does not make, whatever is offered from the outside, to resist happiness, to reject the feast of joy laid before me by insisting that my dark fantasies are real or by failing to act, as I must, to help turn my brighter beliefs into realities. I have seen, in my own life and that of others, how substantial that feast of joy can be when it is willingly accepted.

We have been to the little church where George Herbert, the subject of Bruce’s Master’s thesis, preached. Herbert never sought fame, only devotion. His poem, Love #3, is our favorite, and expresses Bruce’s thoughts beautifully.