The best role for a female Shakespearean actor is Hermione in The Winter’s Tale. Hermione, though absent for much of the play, dominates it with her nobility and grace. Unlike Rosalind or Portia or others of Shakespeare’s strong women, Hermione never puts on a man’s clothes to show her power. She is already empowered. She states it herself when she is brought to trial for adultery, of which she is innocent.

Since what I am to say must be but that

Which contradicts my accusation and

The testimony on my part no other

But what comes from myself, it shall scarce boot me

To say ‘not guilty’: mine integrity

Being counted falsehood, shall, as I express it,

Be so received. But thus: if powers divine

Behold our human actions, as they do,

I doubt not then but innocence shall make

False accusation blush and tyranny

Tremble at patience.

There is much about Hermione for Mormon women to consider. She functions as we might imagine the Heavenly Mother to function–but is seen only in the first and last acts. For much of the play, we think her dead.

As I watched the BYU production this past weekend, I thought about invisible women. Not the kind we might imagine Lily Tomlin performing as a sequel to The Incredible Shrinking Woman, but something more akin to instructions I received last week at the Provo Temple by our temple matron. She asked that we not wear showy jewelry which could be distracting. “In fact,” she said, “we should be invisible. The patrons should be able to see right through us and into the face of God.”

I understand the knee-jerk reaction many women might have to the idea of nurturing invisibility, but I think it gives us much to ponder.

In my musings about what “The Divine Feminine” might be, I sense reverence all around Her. I think of the woman in the Book of Revelation, who has fled into the wilderness.

Revelation 12: 14 And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly into the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished for a time, and times, and half a time, from the face of the serpent.

She is safe, but she is also hidden, just as Hermione is hidden away in a “removed house” until a prophetic demand is met: that which has been lost must be found. Specifically, Hermione’s daughter, Perdita, banished by the king (deceived into thinking the child a bastard), must be restored to the kingdom, which has no women in its reigning family. The king, Leontes, is a lone man, left without even his son (who has died of grief) and facing his own past cruelty daily as he prays at his wife’s tomb.

I have strong feelings about how The Winter’s Tale should be staged. The part in Sicilia, which involves the kingdom of Hermione and Leontes, is a male-dominated place, and I like seeing it with one or two subtle phallic images and deep, rich, but rather dark colors–blacks, deep reds, grays. It is a harsh world, dominated by quick judgment and even the question, “Canst not rule her?” (meaning “your wife”). The intermediate part of the play, which takes place in what I would call Eden is a feminine world, and I like to see pastels, lots of flowers, preferably a lamb or two, birds resting on eggs–every symbol of openness and fecundity. It is a world of music and intuition rather than sharp corners and set rules. The shepherds who dominate this world are not educated or rich, but they are good. They recognize the beauty of a baby. (For Perdita, as a baby, has been left where the shepherds would find her. I would guess that someone has compared Leontes’ threats to kill his daughter with Lady Macbeth’s declaration that she would be able to dash out the brains of the very children she had nursed, as she denies any maternal instinct with the words “Unsex me here!”)

It is in this fertile world that Perdita–raised by a male shepherd and apparently motherless–meets Florizel, the son of Bohemia’s king. Of course, they fall in love. Eventually, all are gathered back into the masculine world of Sicilia, where Hermione is invisible. That world is shadowed now by Leontes’ grief and self-recrimination. Indeed, having chosen to disregard his wife and indulge his jealous imaginings, he is a lone man. Hermione, like the LDS version of Eve, had been not just a queen but a counselor to her husband, aligning her will with her god’s (Apollo, in Hermione’s case), and hoping to return him to his true self, to his intuitive understanding and trust. In one of her most moving speeches during her trial, she has declared:

But yet hear this: mistake me not; for life,

I prize it not a straw, but for mine honour,

Which I would free, if I shall be condemn’d

Upon surmises, all proofs sleeping else

But what your jealousies awake, I tell you

‘Tis rigor and not law. Your honours all,

I do refer me to the oracle:

Apollo be my judge!

In the story of Adam and Eve, as Mormons hear it, Eve mediates between her husband’s word and her revelatory understanding that there will be no progress if the two remain in the garden. They have been commanded to remain together, and that commandment becomes the overriding one. After Adam is persuaded that Eve is right, they leave the garden together and find that they are yet guided by God, and that they will indeed become “as the gods.”

Leontes, having chosen himself over his wife, having listened to his own counsel rather than his god’s, finds his world joyless. By the time we are at the last scene, he has fully recognized that he should have respected all of his wife’s gifts, including her gift of wisdom. She could have guided his conscience like a mediator, or, as we might put it now, like the Holy Spirit.

Her greatest gift is yet to be shown, however: the gift of forgiveness.

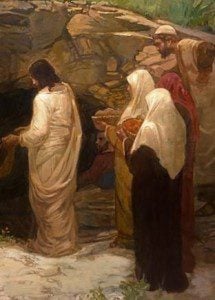

In this Sicilian setting, where Perdita realizes that she is a daughter of royal birth, and severed friendships are mended, Paulina, takes the ensemble to the chapel where a statue of Hermione has been recently completed. Leontes is stunned by the statue’s likeness to his late wife, but confused that there are wrinkles in her visage which she didn’t have when he last saw her. Paulina explains that the sculptor has created this image as though Hermione were yet alive. Leontes finds it miraculous and wants to kiss the statue’s lips. He is restrained by Paulina, who promises greater wonders yet. But first, she says, “it is required that you do awake your faith.” She orders music to begin, and says, “Music, awake her! . . . Be stone no more; approach. Strike all that look upon with marvel.” In a good production, there should be a moment of suspense before Hermione moves. The audience should feel the same wonder as the onstage characters do when Paulina says, “You perceive she stirs.”

Hermione is alive. She embraces her husband in full forgiveness, and then greets her daughter, whom she has not seen in sixteen years. Perdita asks for a mother’s blessing, and Hermione gladly gives it, saying, “Ye gods look down, and from your sacred vials pour your graces upon my daughter’s head.”

In the BYU production, Hermione knelt to give this blessing. More often than not in productions of The Winter’s Tale, according to my brilliant husband Bruce Young, who has made a careful study of parental blessings in Shakespeare’s time, Hermione, either standing or kneeling, embraces Perdita as she speaks this blessing. In Shakespeare’s time, however, the full ritual would have been done.

This is Bruce Young’s description from his book (a must read for anyone directing or teaching Shakespeare, and one which all universities should have, since it gives rarely known information on Renaissance customs, which illuminate much of Shakespeare):

The parental blessing was one of the most important and pervasive rituals of early modern England. Indeed, according to contemporary observers from France and Italy, it was a peculiarly English custom. It goes back at least to the 1200s, and probably much earlier; it appears to have been practiced after the Reformation by Catholics and Protestants, Puritans and non-Puritans alike, with little variation in form or meaning into the early seventeenth century. In “well- ordered” households the ritual took place daily, morning and evening, with children kneeling before their parents, both father and mother, and saying (to quote William Perkins), “Father I pray you bless me, Mother I pray you bless me” (Treatise 469), or words to that effect. Each parent would respond to the request by calling on God to bless the child, usually while placing both hands on the child’s head to signify the conferring of the blessing. Along with the blessing, parents would sometimes give a child counsel intended for his or her benefit. Some continued to ask their parents for blessings into adulthood. Accounts of this practice range from the early 1500s—for instance, Sir Thomas More reportedly would kneel publicly before his aged father and ask for a blessing—into the 1600s, when a Venetian ambassador reported seeing Londoners kneel in public places, “no matter what their age,” to ask a parent’s blessing (52) .

When I incorporated the “resurrection” scene into my play Dear Stone, about a woman’s descent into paralysis from her multiple sclerosis, the director did stage the mother’s blessing as it would have been done in Shakespeare’s time–with the mother’s hands on the daughter’s head. I was aware even then (1996), that a mother’s blessing on a BYU stage might be controversial. There were no complaints. In 2015, however, there is a concerted effort by the Ordain Women group to depict women’s blessings often so that people won’t be surprised to see them. I’m afraid it is a misguided effort. Because it is associated with an organization largely perceived as adversarial to the Church, such depictions undermine what could happen were another source, one perceived as faithful, to publish such images. In a recent Youtube done by the Ordain Women group, Jane James, a black convert who joined the LDS Church in 1843, is shown with a white pioneer giving and receiving the laying-on-of-hands blessing. The irony is that Jane herself recounts an incident which involved her giving a blessing to a white child, so the invention of this undocumented scene is odd.

These are Jane’s words:

In course of time, we arrived at La Harpe, Illinois–about thirty miles from Nauvoo. At La Harpe, we came to a place where there was a very sick child. We administered to it, and the child was healed. I found after [that] the elders had before this given it up, as they did not think it could live.

Since Jane was “the leader of this band” (as she puts it in her life story) we assume that she not only participated in but likely led the effort to administer to the child. It is a fact that Mormon women pioneers gave blessings to one another by the laying on of hands. It is also a fact that we still do it, though usually just in the temple. There is nothing unusual at all for me to see a woman blessing another woman. I witness it and do it every Tuesday in the Provo Temple. I believe that the fuller tradition–women’s blessings outside the temple–will be restored in time with the recognition of equal but complementary roles in priesthood. We continue to grow as a church, and the restoration continues.

I would have loved to see Hermione give a true, hands-on mother’s blessing to Perdita in the BYU production, but I did love the costuming, which suggested a Mother in Heaven-type of divinity. Hermione, in that last scene, wore a crown which reminded me of a halo, and had a raised, tall collar which I could picture as wings. Or perhaps the crown could be seen as stars, thus making Hermione much like the woman of Revelation 12–with the stars above her head and the moon beneath her feet. She was dressed in white and lit in a way that suggested a goddess. I thought the depiction magnificent.

Hermione dominates The Winter’s Tale, though she is invisible for much of it. She suggests both the woman in Revelations 12 and, for Mormons, Eve, the mother of all living, who is heroic in her advocacy of what she knows to be the best path. Hermione, like any priestess, becomes an intermediary between the divine world and the immediate one as she asks the gods to “pour graces” upon her daughter’s head. She is fertile. In fact, when first we see her, she is pregnant. (I remember portraying Hermione in my high school’s production of the play and coming onstage with a small pillow strapped to my stomach. I heard that a friend said, “Oh my gosh! Maggie is pregnant! Why didn’t she tell anyone?”)

Seen alone and without context, the pregnant queen is the quintessential Divine Feminine.

There is much to instruct and to inspire us in the play. As we Latter-day Saints continue the restoration of the gospel, we, like the characters in Shakespeare’s play, must also be patient and believing, ready to behold miracles. As we seek these miracles, we will start seeing them. But first and foremost comes Paulina’s instruction: “It is required you do awake your faith.”