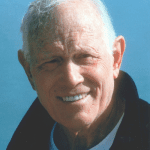

I am writing this talk at my father’s hospital bedside. We are in the final phase of his life, though we don’t know how much sand remains in the hourglass neck.

When Dad was in the ER on Saturday, I sat at his bedside, a few feet from my mother. Mom gave family news, and smiled and laughed as though we were at the dining room table, not in the ER. I kept my eyes on Dad. I watched him curl into fetal position. He moved his hand between the bars of the hospital bed to hold my mother’s hand.

These moments—the final ones—are all about the bodies we have grown to love, the forms we have learned to recognize as part of ourselves, those we have surrendered to, bonding so tightly that we know the inevitable parting will rip into our cells, force a groan through our veins.

In this presidential address, I have decided to pay tribute to my father within the context of our conference theme: Liberating Form.

Foundational to my father’s identity is his faith in the gospel as framed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. If that faith ever wavered, we Blair kids didn’t know it. We were raised to believe the fundamental Mormon doctrine—that mortality is a part of eternity, during which we take on bodies which can and must experience a range of emotions and sensations—including sorrow. We understood that there was no other way for us to truly progress in goodness, compassion, and love. We Mormons believe that God himself has a body, one which can also grieve. We believe in “a weeping god,” as Gene England put it. This ability to weep is attached to our relationships.

I was my parents’ first teacher in the long, segmented course in progeny-based grief: I was a colicky baby, a temperamental toddler, a flailing teenager. And from second grade on, I was a writer.

That talent, that passion to create stories, came from both my parents, but perhaps mostly from Dad. He is a linguist, and uses stories as a cultural bridge. The story he uses most frequently is “The Prodigal Son.” He revises it to fit whatever culture he is moving in to. So, when he tells the story in Mayan, the prodigal son grows his hair long during his wandering—a cultural symbol, for the Mayan audience, of rebellion.

Dad always tells the story in simple, sometimes repetitive sentences, because he is teaching not only a story but a language. Of course, his audience already knows the basic language of the story, the emotional idiom which undergirds it, because they have been either the child leaving home or the father (or mother) running to greet the long-lost child.

These are my father’s words:

Emaciated and weak, Johnny ate pig fodder and swill. Soon sick, and with no one there to attend to his desperate need, he cried out in agony: “Oh, God, what have I done? Help me, God. Help me return to my father. I’ll say to him: ‘Father, I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Make me only as one of your hired servants.'”

Now Johnny got up and set out for home. I can imagine him walking along dusty roads, climbing hills, descending into valleys, passing through fields and wilderness. He is aching within. Sweat mixed with tears streams down his face, but his every step is quickened by hope.

Nearing his father’s lands, he wondered, “What if Father’s heart has turned against me?” (Oh, but how little he knew of his father’s heart!) How he longed to see his father’s fields. He remembered the happy days of his childhood, pleasant hours spent at play with his brother, times that he was working, playing, singing, and chatting with his dad and mom.

Now Johnny came within sight of his father’s house. His father was standing on a hill from where he could look down on the road. Every day he had stood there, hoping to see if by chance his lost son might be coming up the road. And that day, as always, he was there hoping and praying. Suddenly he saw the figure of a young man approaching. His heart jumped. The boy’s clothes weren’t recognizable. They were tattered and dirty. The boy was limping. His hair was long and disheveled. But the father recognized his son, and his heart filled with compassion. Johnny had come home! He ran joyously to meet his son and threw himself on his neck and kissed him. “Johnny, my son, you’ve come back!”

But the son said to his father, “Father, I have sinned against God.”

“Yes, Johnny, I know.”

“I have sinned before you, Father.”

“Yes, my son, I know.”

“Oh, I am ashamed, Father. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.”

“Johnny, my son, my son. How terribly you must have suffered.”

The father called to his servants: “Bring clean clothes and dress my son. Put shoes on his feet. Put this ring back on his finger. Come, let us celebrate. For this my son was lost but now is found. This my son was dead but has returned to life.”

Even in Mainland China in 1980, Dad’s students personalized the parable, and imagined that they were the prodigals who had strayed.

In the story’s structure, the father sees his son “from a great ways off” (Luke 15) and runs to him. They meet on the path, not at the threshold of the ancestral home. The father has to go some distance himself to reach his son.

It is at this juncture—the place between home and not home; the path between loss and restoration, that much of our best art happens. We wonder how or if Golden Richards will tame his wandering heart in Brady Udall’s The Lonely Polygamist. How will the various characters in Eric Samuelsen’s Accommodations negotiate the slippery borderlands between love and greed, pretense and truth, half-hearted accommodation and true reconciliation?

Each story leads us back to our own hearts, our own tears. This fundamental doctrine of Mormonism—the need of corporeality—becomes a gift. Our ability to feel pain and even to inflict it gives us power to understand how consequential our choices can be. We may choose to rescue rather than avenge—or vice versa. We may choose to heal or to look away; to feed the hungry, or to count our own accumulations. Our bodies, complete with nerves, organs, and the ability to think, to contemplate, and to forgive, press us to repair rifts, and to see an image of God in every face we encounter. We are called to responsibility by every person we meet on the path, whether they are heading home or running away. Reverberations of our scriptures ripple through our stories.

I have wept with my father in my own journey as a mother. As one of my daughters developed an eating disorder, I refused to talk to anyone but my husband about it for a long time. Her disorder was evidence of my failure, and I could not get past my own shame to run to her when she was “a great ways off.” I didn’t know how, and it seemed certain that she’d flee as soon as she saw me.

Dad had gotten very ill by this time, and was on dialysis three times a week. For years, he had felt that he never quite got the balance right between family and career. He often went to foreign countries during the summers, and was frequently at his office at absurdly early hours. Now, however, he was bound to his body’s failure, sitting in a chair amidst a ganglia of tubes and monitors, his right arm stretched out on a table, his veins having been joined to accommodate the fistula, where the dialysis needle was inserted and his blood was cleaned during a four-hour procedure. He was grounded.

I never approached without him looking up at me as though I were an angel making a surprise visitation. “Hello, Margaret! How wonderful to see you,” he’d say. Then I would talk, and Dad—unable to move, yet moving nonetheless into the uncertain and grief-shadowed world I was in–wept with me. I don’t remember everything I told him; I simply remember his tears.

I do know what I wrote to my daughter as I tried to reach out to her, acknowledging the magnificent anguish of motherhood.

Dear Daughter:

When the midwife put you in my arms and I saw that darling dimple for the first time, I had no thought of how painful your delivery had been. My only thought was that you were the most beautiful baby I had ever seen, and I wanted to make your life full of joy and laughter and wonder. Forgive me for any ways in which I failed to do that. As you know, I have my own struggles and usually fall short of what and who I want to be.

I often didn’t recognize or acknowledge your pain and even now, I am yearning to comprehend it. I was often so involved in my own projects that I didn’t realize you were slipping into a mire of fear and anxiety. Too often, I put pressure on you to do better when it was all you could do to keep from collapsing into your own insecurities and despair.

In this note, I am not the parent welcoming the prodigal home, but more like Lear in the final scene of Shakespeare’s play, when the king, who has disowned his daughter for failing to meet his expectations, sees her as she truly is—a being more glorious than he had ever imagined. At first, he thinks her an angel, then revises himself: “I think this lady to be my child, Cordelia,” he says. “And so I am,” she answers. “I am.” She kneels to ask for a father’s blessing, and he simultaneously kneels to her. In this reconciliation, parent and child face one another , in repentance and forgiveness.

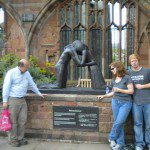

The statue titled “Reconciliation” at the ruins of Coventry Cathedral—bombed during World War II– uses that same image: man and woman kneeling to each other, embracing, weeping together. We do not know what divided them, just that they have been reconciled. A replica of the same statue stands in the peace garden of Hiroshima, Japan.

At Coventry, this statue is positioned a few yards from the remnants of the old cathedral. The new cathedral features a cement awning which extends to the ruins, the last two meters like the architect’s blessing overhanging the bombed brick.

When my family and I visited the scene last summer, I gazed at the two cathedrals, one a monument to a devastated past, and the new one a monument to hope. I recited Cordelia’s words: “Hold your hand in benediction o’er me.” The structures themselves testify of redemption. Their very forms give the message of liberation, the placid present calming the disrupted past. A blessing.

A few weeks ago, my nephew’s girlfriend, Dia, was preparing to enter the Missionary Training Center. Her father is not LDS, so she asked Dad to give her a blessing. He was at home then, resting. We took a chair into the bedroom and woke Dad up. Dia sat down, and Dad arose, unsteady at first, but fully accustomed to the position he would assume. He stood behind the chair, placed his hands on Dia’s head, prefaced the blessing in the designated way, and promised her comfort, the gift of tongues, health. Recognized forms were respected, but the energy of love lifted my father’s words from any set script into revelation and prophecy. Each of us present felt a swelling of love for Dad and for Dia. We embraced one another when it was done.

There is something divinely powerful about an embrace. I learned it most profoundly in my hardest mothering moments . I don’t recall exactly what I told Dad, but I have a record of my thoughts:

My daughter is having panic attacks. There are definite physical symptoms. She came up to Bruce’s and my bedroom at 2:30 a.m. shivering and with her heart racing. I opened the blankets and let her in. She hasn’t been holdable for awhile. In fact, last night during our scripture reading, she was very on edge, and when Bruce touched her arm she snapped, “Don’t touch me!” But at 2:30 a.m., there was no resistance. I pulled her into a tight embrace as Bruce transitioned into wakefulness. She asked for a blessing, and he got up and came to where she and I were lying.

For the next four hours, I held my daughter, stroked her head, neck and back. She needed me to talk calmly to her, so I started: “And it came to pass in those days that there went out a decree from Caeser Augustus, that all the world should be taxed…” I told her the Nativity story, then the story of Jesus accepting the anointing oil of a woman whom his disciples considered of bad reputation—the stories that frame and sustain my faith.

Both the tight embrace and the whispered stories were part of liberating my daughter from the horrors of her anxiety, from a condition we learned was called “derealization”—a sensation that all surroundings and you yourself have ceased to be real. We learned this name because my sister had also suffered from it. Sometimes I would have my daughter in my arms and my sister on the telephone, coaching me. “Rub her feet. Her blood needs to circulate. Keep talking to her. Tell her you’re real, that your arms are real. Tell her she’s safe.”

From my sister’s experience, I was able to approach an understanding of what my daughter was suffering. And even if I couldn’t fully comprehend, I was instructed in how to respond. My heart was enlarged to encompass my daughter and this nightmarish maw into which she had been plunged. In coaching me, my sister was an artist, using words and images to help me understand. “It’s like you’re a doll. Nothing is real. Nobody is real. It feels like the walls and the floor could disintegrate, and there’s not a thing you can do.”

“I’m real,” I would whisper to my daughter. “My arms are real. You are surrounded by love. Do you remember the story of Joseph in the Old Testament? Let me tell you that story.”

Tuesday, March 22, 2011:

Dad has been moved to the third floor of the hospital. My daughter has now joined me, my sister, and my sons in his room. I continue writing my talk, and my sister tells me we can listen to my father’s devotional, which is available in an audio file on the internet.

We turn it on and hear the long introduction of Robert W. Blair, and his work on various the Mayan dialects, including Cakchiquel. I remember seeing Dad, who had already written a book on Cakchiquel grammar, standing before a congregation in a village called Patzicia. He says (in Spanish), “I am happy to speak Spanish, but if you don’t mind, I would prefer to use Qa Chabel.” (That means “Our language.”) Indeed, the tall Gringo spoke it and bridged the worlds, meeting the people where they were.

Dad’s friends and colleagues often ask me how he’s doing. I give honest reports. Several have said to me, “Your dad changed my life.” Each of them has ventured into foreign worlds and found paths to common understanding. Each has learned to love other cultures, and usually to speak the languages of these other places. Often, Dad’s stories have been part of the bridge.

Any of us who attempts to write the kinds of things which AML honors must be bridge builders, finding the ground where our readers can meet our characters and even recognize themselves, honoring the ways people think and speak—in any or all cultures. At some level, the words we write and read should enlarge our hearts—even “wide as eternity,” which is how LDS scripture describes Enoch’s heart after he sees the children of the weeping God, who are without affection, who hate their own blood.

Today, Saturday, March 26th, I conclude this address returning to my father’s devotional. “Reconciliation,” says my father, “is a gift we can and must give to others. It is a gift we can and must receive from others.”

To artists or supporters of artists, my father’s desire and invitation has particular significance. Our work leads us to one another, gives us a sense of journeys we perhaps have not ourselves taken. It places us on the path—often far from familiar surroundings—where we meet sons and daughters, fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters. Though we might not have not recognized the family resemblance before, we finally see it in merciful light.