Sculptor Joe Cajero was raised on the Jemez pueblo in New Mexico and his work is informed by his Pueblo religion. Here is how he describes his work, which he calls “The Embodiment of Prayer”:

Sculptor Joe Cajero was raised on the Jemez pueblo in New Mexico and his work is informed by his Pueblo religion. Here is how he describes his work, which he calls “The Embodiment of Prayer”:

My creative energy is often spiritual in nature. Each of my sculptures invariably represents some aspect of praise and appreciation for life’s beauty, ebb and flow. “The Embodiment of Prayer” is a created image that specifically captures what is a reflection of my spirituality. Since my Pueblo religion restricts the realistic unveiling of ceremonial life, I am constantly challenged by the use of abstract art to represent the sacred.

This masculine form is the expression of my intercessions with God on behalf of mankind and our tumultuous world. His mouth is both elongated and vibrant with energy as he sings for all creation a song that is eternal. His headpiece represents the blue sky of day as well as the majesty of heaven. The figure is made up of three distinct sides that bring meaning to the whole.

The front left side is divided into four panels, each embodying a sacred element of life. The wavelike pattern in the top panel represents not only the life giving properties of water, but also the never stagnant flow of meaning and purpose within the individual, moving from generation to generation. Stars of various sizes make up the second panel representing the night sky and the harmonious order of the universe. The third panel celebrates the organic element s of life, earth and all that have been nourished by her. Large and small altar (kiva) steps framing this panel symbolize the prayers of adults and children while the swirling texture within the framework of the kivas is reminiscent of the ancient, hand-finish found on the kiva walls. The fourth, bottom panel has raised circular designs, each of varied size and texture. The circle represents the maturing of the soul while its texture speaks of the soul’s desire for God.

The front right side of Embodiment is a place of shadows reflecting the trials and tragedies that are common to all people. Examining my own period of depression caused by personal loss. I experienced four periods of growth within the emotional darkness. An altar shrouded in blue represents each of these four phases and dragonflies sail beyond the altars free from the darkness. Like nymphs emerging form dark waters to fly on wings in the air, so might man emerge from his own dark moments. We experience this place of beauty by choosing to embrace the freedom of forgiveness, letting go of the past and embracing the present with soaring hope for the future.

The backbone of Embodiment is a stately stalk of corn. This life-sustaining food is central to Pueblo spirituality, being regularly used in prayer and Pueblo ceremony. A magnificent symbol of renewal and regeneration, corn is ever faithful to grow toward the sun and sway joyfully with the wind.

May your life be so blessed that you too might dance in rhythm with the Creator.

Whenever we draw comparisons between religious traditions we run several risks (often in the name of noble goals):

- We run the risk of erasing the unique voice of the tradition that is not our own, by assuming that someone else’s religious values are ours.

- We run the risk of reducing the voice of our own religious tradition and everyone else’s to mere platitudes that we all supposedly share — ignoring the history, experiences and perspectives that shaped those traditions.

- Although our purpose is often to foster understanding and dialogue across our religious traditions, we build a conversation that inadvertently erases those differences before the conversation — and the listening — ever begins.

- We also run the risk of assuming that one individual’s interpretation of a tradition is representative of everyone who identifies themselves with that religion. That’s never the case.

I can’t speak with authority about Pueblo religion and practice, so if you are interested, I would encourage you to talk to those who are authorities on the subject and / or read about their work. Joe is one of the most creative, gracious and thoughtful representatives of Pueblo spirituality. Just studying his work would be one way of probing the depths of that tradition.

On another level, of course, art invites us to do our own reflecting and work. Joe’s work has provoked me to think about my own understandings of prayer and the spiritual life. I can speak with a bit more authority in that regard and here are some of the observations that I draw from his sculpture, “Embodiment of Prayer”…

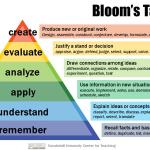

One: Our lives are lived out in constant contact with both heaven and earth — the presence of God and the mundane realities of daily life. Many of the struggles that we experience in our spiritual lives arise out of a failure to honor our connection with one or the other — or both.

Two: We cannot be spiritual alone. Prayers are lifted in community. There are moments when the only prayers to say are the prayers we say on behalf of others.

Three: Prayers are not something we offer when we are in the best of places, nor are they just for moments of crisis. Nor is our spiritual growth confined to best of moments. They are thread through the whole of life, in moments of light and in moments of darkness.

Four: Prayer reminds us that we are not meant to live in careless disregard for the world around us. By the same token, we are not to be trapped by it. We are mortal, but we are made in the image of God. Prayer reminds us of our dependence upon God, but it also reminds us of our relationship with God. We almost always misunderstand and misuse that gift when we forget one or the other dimensions of the lives we have been given.

Five: Prayer is not an activity. It is a state of being. We were not meant to pray, but to become a prayer. We are not just meant to say prayers, we are meant to embody a life of prayer.

Joe, thank you!