End of year lists are about quality, not quantity, so I try to eschew comments about the strength or weakness of a given year based on how hard it may be to fill out the bottom half of the list. By most any measure, though, 2011 was a grand year for new films. There were plenty of films to choose from, and for the first time, I thought I could have extended beyond the standard ten films that occupy such lists and still be naming films that I was unreservedly enthusiastic about (The Muppets, Better This World, I Wish). At various points in the year, I considered five different films for the top slot. Normally that might mean that there was no runaway film that I really fell in love with, but the opposite was true. The difficulty in picking just one was reflective of the different ways in which I adored each of these films.

10) A Dangerous Method — David Cronenberg

The film that surprised me the most on this list. I have never been a Cronenberg fan, and I went into the screening having heard mixed things about the film, particularly the script by Christopher Hampton (whose previous work, including Mary Reilly, Carrington, and Atonement did not exactly blow me away). Each work of art is its own experience, however, and sometimes, if you let them, artists with whom you have never connected will find subjects that genuinely engage you. Be slow to dismiss work based on artists’ previous work, especially if you recognize that they have genuine talent and your reservations are more thematic or stylistic.

Keira Knightley has been justly praised for her performance which is, paradoxically, both dramatic and self-effacing. All the contortions (and really, I’m still trying to figure out how she jutted her jaw out so far) are the stuff that could easily come off as bombastic, or, worse, as mugging. Her Sabina, however, becomes even more interesting as she develops, and there is a note of wistfulness in her interactions with Fassbender’s Carl Jung that imbue these people, twisted as they are, with pathos.

Quite frankly, though, the thing that I admired about the film was that it was not afraid to be about something. In other hands, this material would have been about romantic entanglements, using Jung’s fame as a means of reeling you into what would then become a conventional conflict between marital duty and romantic inclination. The Freud/Jung backdrop, though, raises the stakes…or at least it did for me. Is our behavior governed by something more than/other than sexual desires? If so, what? I am not sure that the film gives much in the way of answers, but I was fascinated by its questions.

9) Being Elmo: A Puppeter’s Journey — Constance Marks and Philip Shane

Speaking of films that I resisted, Being Elmo played at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in March, but I didn’t catch it until a brief theatrical run in December designed, I suspect, to coincide with The Muppets.

I missed the Elmo ascendancy, probably being a few years too old for Sesame Street by the time the “Tickle Me” phenom hit the small screen. (One of the film’s more understated but still perfect moments is when Elmo creator Kevin Clash expresses befuddlement at the “Tickle Me Elmo” concept since Elmo never says “I” or “Me” when he is performing.)

As I stated in my full review, Being Elmo works on several levels: personal narrative, cultural history, and art process documentary, to name a few. One issue that I didn’t mention in my review was race. It is fascinating to me that one of the most beloved family icons in the world was created by an African-American. Most people probably have no idea who Clash is, much less that he is Black. I didn’t until I saw the film. Being Elmo doesn’t talk about race directly very much, but it undeniably shaped Clash’s life. He mentions part of the draw of Sesame Street was the fact that it was the only thing he saw on television where there were people of color. At least once in the film it was mentioned that Jim Henson did not have any African-American puppeteers working for him and that this was a fact that Clash could use as a hook to try to land a spot on the team. He appears genuinely more interested in learning his craft and earning his way in the world, however.

The depiction of race, like much else in the film, is nuanced rather than heavy-handed, giving the viewer room to contemplate the meaning of what is being shown rather than having it prefabricated. Is that not what great art should do?

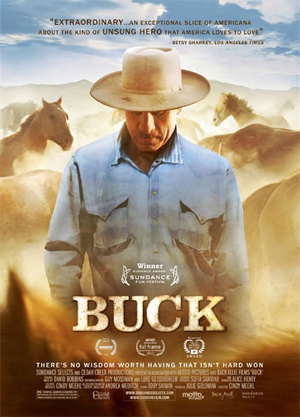

8) Buck — Cindy Meehl

A people’s choice award winner at both Sundance and the 2011 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, Buck, like its subject Buck Brannaman, gets a lot of mileage by whispering where others would shout, gently pulling (at the heartstrings) where others would yank. I haven’t been on a horse in over a quarter of a decade, so it is not as though a depiction of a real life horse whisperer (Brannaman was technical adviser–and some think inspiration–for the Robert Redford film) sounded like something I would appreciate.

A people’s choice award winner at both Sundance and the 2011 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, Buck, like its subject Buck Brannaman, gets a lot of mileage by whispering where others would shout, gently pulling (at the heartstrings) where others would yank. I haven’t been on a horse in over a quarter of a decade, so it is not as though a depiction of a real life horse whisperer (Brannaman was technical adviser–and some think inspiration–for the Robert Redford film) sounded like something I would appreciate.

Brannaman says at one point that he does not think he is helping people with horse problems so much as helping horses with people problems. Maybe that is the difference. The film is about people, and people, even if they are interested in things that don’t necessarily interest you, are themselves always interesting.

“Transcendence” is a word that gets bandied about quite a bit in Christian film criticism. Generically, to transcend is to excel, but at its root the word means to rise above. “Transcendent” is probably the perfect one word review of Buck, which is, in many ways, about rising above. That someone so gentle, so committed to gentleness, could be shaped in the fires of abuse (with typical understatement, Brannaman says “my dad had a violent temper”) makes Buck a narrative of personal transcendence.

I am not a horse person, but earlier this year I lost a beloved pet of many years. Buck suggests that our relationship with animals can act as a mirror to our souls. At the very least, it gives us a glimpse of what it means to be human and in a relationship with great power imbalances. The greatest and strongest of us woo rather than ravish, call rather than coerce. Who does that sound like?

7) Le Havre — Ari Kaurismaki

Immigration was a major theme in several quality films this year, and Le Havre might rightfully share a slot on this list with Ermanno Olmi’s The Cardboard Village and Chris Weitz’s A Better Life. What sets Kaurismaki’s fable apart? Perhaps it is the integration of the spiritual with the political, as shoe shiner Marcel Marx must find a way to keep living, day by day, while his wife lies dying in the hospital.

Really, though, the reason I found myself thinking about Le Havre in the weeks after viewing it had less to do with theological or political correctness and more about its portraiture of human kindness. It mattered to me that Marx was not the only human soul in a world populated entirely of heartless and selfish bastards.

In that regard, the film that Le Havre most reminded me of was, oddly, Lars and the Real Girl. About that film, I wrote:

So many films fear we will get lost and never work our way back to the star, the protagonist, the hero, and thus strip the world he or she occupies of anything good, or beautiful, or admirable, making us cling to the protagonist not because he or she draws us, but because like Private Mayo in An Officer and a Gentleman, “[We ] got no place else to go.”

Not everything nor everyone in Le Havre is who or what he or it appears to be. That’s not because they are deceitful or misleading but because we too often don’t look very closely. This theme seems fitting to me in a film about people, immigrants, that we so often look past and through.

6) Mysteries of Lisbon — Raoul Ruiz

Earlier this year, sportswriter Joe Posnanski wrote a wonderful column about Ron Santo at long last being voted into the baseball hall of fame…after he finally died. Raoul Ruiz passed away in 2011, and Mysteries is about as accomplished a swan song as any artist could hope to have.

I can’t quite shake the feeling, though, that the media blogsosphere, with its “what’s next is already five minutes ago” mentality of needing to get out in front of the next big thing has largely avoided taking stock of the film (which is admittedly hard to know what to do with) by consigning it prematurely to the halls of film history, considering it, if at all, as part of a Ruiz retrospective piece rather than as a stand alone work of art.

An annual survey of Film Comment‘s contributors ranked the film as the sixth best release of 2011, but a four and a half hour run time meant few theaters outside of festivals actually played the film. I understand, too, the potential complaint that the film looks and feels too much like the television miniseries it was originally intended to be. Much like Ceylan’s Once Upon A Time in Anatoulia, however, Lisbon uses length to create a fuller, richer portrait of its subject matter. Based on a Portuguese novel, the film begins with Joao, a boy with no last name who is growing under the watchful eye of Padre Dinis. I was set up to think the whole film would be about solving that one mystery, but the parentage issue is seemingly resolved quite early. Finding out the identity of Joao’s mother is simply the first domino, and one of the fascinating structural elements of the narrative is how many stories, past and present, get itntertwined.

Lisbon has drawn comparisons to Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, and while I like that comparison, I found it less Romantic (with a capital “R”). Watching it, one is reminded of just how much contemporary films, even those lauded for their alleged depth and/or subtlety lead their viewers (at least emotionally) by the nose. Lisbon shows you a lot, but it rarely tells you what to think about what it has shown you, and for that reason its run time is a welcome space that allows you to form your own opinions. Once you do, the characters’ actions take on different shades of meaning in your memory and/or in subsequent viewings. That a two hundred and seventy minute film made me want to re-view it when I was done is itself quite an accomplishment.

5) Hot Coffee — Susan Saladoff

Another running theme in this year’s list is masterpieces from surprising places. That a documentary about tort reform would be my favorite documentary of the year is unexpected. That it would come from a lawyer turned first-time director is a testament to the power of truth, passionately spoken, to cut through our stereotypes of what great art is and what great artists look and sound like.

I first screened Hot Coffee at Full Frame in March, and I half expected my initial, positive, response to wane as the enthusiasm of the festival crowd faded into memory. As the year progressed, though, I found myself returning to the documentary again and again. My wife wanted to see it. A student preparing to go to law school asked if he could screen it with me. My sister-in-law, battling colon cancer, read my review and suggested we could watch it together when I visited her. (It was one of the last films we watched together and discussed before she died.) Each time I re-watched the film, I kept thinking I would get bored with it–or that the person I was watching it with would have a contrarian reaction. Instead, I found myself more engaged, and I witnessed an undeniable pattern in an array of viewers from different walks of life finding common ground in their appreciation for the way in which the documentary articulated some of their most fundamental frustrations at the state of contemporary American politics.

When I asked director Susan Saladoff why she thought the film managed to successfully cut across party lines, she said with typical simplicity and directness, “Because I tell the truth.”

People are hungry for the truth, she opined, and frustrations over the global financial recession have made many people realize how often they are lied to and manipulated by politicians and the media. That frustration is not limited to one party, nor is veneration for the American Constitution. (The film points out that caps on damages and mandatory arbitration clauses can and have been challenged on grounds that they violate the Seventh Amendment.)

Saladoff also said that the experience of making the film confirmed some important life lessons as well: “Follow [your] heart” and “do something you are passionate about.” Although individuals can feel helpless and hopeless in the face of political and social forces, sometimes even changing people’s attitudes “one degree” is enough to result in positive changes in the world around us.

Perhaps the best part of Hot Coffee was that it gave me, a cynic by nature, hope. I was disappointed to hear that HBO took out the “take action” suggestions at the end of the film, but they are still available as extras on the DVD. Never doubt that a single voice can change the conversation, and then the room, the house, the block, and beyond. Stella Liebeck did. So did Susan Saladoff.

4) A Separation — Asghar Farhadi

At the Toronto International Film Festival, Ashar Farhadi mentioned that the conflict between Nader, an Iranian man and Razieh, the woman he may have greatly injured (or who may just be extorting him) was as much about “class warfare” as it was about genders clashing.

One of my standard defenses of film art when I am forced to engage those who think exposure to it is demoralizing (in the strictest sense of the word) is that art can sometimes reach places argument cannot–that it is hard to buttress the imagination against conscience and truth.

There are a lot of truths in A Separation that are worth hearing, none more so than that one of the greatest perversities of the human race is its capacity to try to bend the truth to make it serve us and that legalism is a kind of bondage that can drive us away from our best impulses, making righteousness more important than goodness.

In a year in which Jafar Panahi’s imprisonment dominated news about Iranian film, it was a small balm that other directors continue to push for ways to make art within and about a culture that can too often seem alien (rather than just foreign) to the rest of world. That it seems alien at times to the people living in it is a reminder, too, that the things we have in common perhaps outnumber the things that so easily divide us.

Full review here.

3) The Kid With a Bike — Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

As I have approached finalizing this list in the last month, I have spent a lot of time contemplating whether or not, had The Kid With a Bike been directed by newcomers or relative unknowns, the response to it might have been euphoric rather than warm and respectful.

Is anyone a bigger victim of their own success and its consequent heightened expectations than the brothers from Belgium? Last I looked Kid was 91% fresh at Rotten Tomatoes, but you don’t see it on too many lists of the year’s best.

Perhaps that might have something to do with its thematic overlap with previous Dardenne work, but there are new plot wrinkles and developments in their thinking that I think are easy to overlook given the limited focus of their oeuvre. For one thing, there is an element of mystery (in the Christian sense of the word) in their more recent work–God’s presence is shrouded rather than simply missing from the fallen world. While the focus remains on human relationships–and those relationships continue to be the primary vehicle through which God reveals himself and works in the world–The Kid With a Bike also invites us to think about ways in which God’s hand guides, motivates and empowers those human vehicles, as well as whether or not He can and does act independent from them. That is, the film invites us, however indirectly, to contemplate whether other humans are the only means through which God acts or only the most common. Altruistic love in a fallen world is a miracle, yes, but is it the only kind God yet creates?

Review from the Toronto International Film Festival here.

2) Win Win — Thomas McCarthy

Thomas McCarthy is another writer/director whose consistency makes it easy to overlook.

Just as its predecessors The Visitor and The Station Agent, Win Win is populated with more fully rounded and realized characters than you might find in a handful of commercial Hollywood releases. What distinguishes Win Win from McCarthy’s previous two films is a slightly more fully realized plot. Oh, it is still more about the people than what happens to them, but one feels like they have more to do than simply occupy the film and talk with one another.

The story of an increasingly desperate lawyer and part-time wrestling coach who struggles to extricate himself from moral and financial quick sand (only some of which was caused by his morally compromising himself in the first act) is at turns tender and terrifying.

Like The Kid With a Bike, Win Win is in some ways about charity–who, if anyone, deserves it and what motivates the people who give it. (I found it fascinating when, where, and how often, Jackie, the wife and mother of the piece, used the words “have to.”) It’s not just a film that invites us to think about characters who do or do not act charitably. It is also one that invites us to examine our own responses to the people in it.

Is Mike Flaherty (Paul Giammati) a better guy than an allocution of his crimes in a court of law might suggest? What makes us think so? Is it only that our judgements of his sins are tempered with a knowledge of his graces? Or is it that honesty makes us for once concede how easily it might be to find ourselves in his shoes but without the community service or surrogate fatherhood on our ethical vita to prop up our sense of self worth?

Win Win was released early in 2011. It is the only narrative film (along with the two documentaries Hot Coffee and Buck) that is widely available already in DVD format. One would think that would give a film an advantage–plenty of time to find its audience. But familiarity does often bring contempt, and critics love nothing more than to get out in front of critical consensus. Time also gives naysayers plenty of time to pick nits: an early scene relying on homophobic comedy falls flat, the ending felt rushed to some (though perfect to me).

At the end of the day, when a distraught and largely reticent Kyle (sublimely played by Alex Shaffer) asks to be left alone, the response–and timing of it–of Mike and, especially, Jackie is so pitch perfect, it may have been my favorite single moment of the movie year.

1) Tyrannosaur — Paddy Considine

My friend and colleague Elizabeth Rambo says that she will make end of year lists, but she refuses to rank the films in them. I understand that sentiment even if I can’t quite bring myself to emulate her practice. My end of year lists have always been comprised of personal favorites as much as films that won my critical esteem. There should be overlap in those two circles. They may be close to identical. A place in the circle usually has more to do with the latter descriptor. The position, once in, has more to do with the former.

I saw screened Tyrannosaur twice in one week while at the Toronto International Film Festival, and I was surprised at how much of the raw, emotional power of the telling was retained on a second viewing. It is the portrait of a hard man with a hard heart who is softened by his tenuous relationship with a woman he would seem unlikely to meet in any way except the way he does.

I suppose the easy, lazy critical cliche is to call Tyrannosaur a strange love story, but, really, it is less about how the characters feel towards one another than how they act towards one another. I read once that the surest sign of love’s authenticity is whether or not your relationship with someone else makes you a better person. To the extent that is true, I can buy that Hannah (Olivia Colman, who deserves an Oscar) and Joseph (Peter Mullan, ditto) feel something that it is not entirely meaningless to use the signifier “love” to designate. It is easy enough, too, to see the qualities in each that would engender the feelings they struggle in vain to verbalize.

One thing that makes Tyrannosaur exceptional is that it is about emotions that are so often scorned and misunderstood in our hard, too cool for fools, culture. It has more to say about fear and unjust shame than a dozen remakes of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, and its portrait of despair is as empathetic as Melancholia’s without that film’s snobbish condescension. Hannah’s longing for answers from God resonated more deeply with me than all the dinosaurs in Tree of Life put together.

Few things in this inscrutable universe are as strong or as fragile as the human spirit. This is a paradox, and a mystery, and a truth.

****************************

Ten very honorable mentions: A Better Life, Better This World, Chicken with Plums, An Encounter with Simone Weil, I Wish, Machine Gun Preacher, The Forgiveness of Blood, Making the Boys, The Mill and the Cross, The Muppets.