Part I: Subtext is Real…But What is It?

“You’re reading too much into it!”

“Do you really think [the author/artist] meant it to be taken that way?”

“Aren’t you just interpreting it to suit your agenda?”

Any teacher of art or literature has heard these complaints and questions scores of times. Perhaps the only one who hears them as often as the professor of literature is the film critic. I am both, so I’ve heard these remarks, or variations of them, regularly over the last two decades.

Sometimes the questions are sincere. Most of the time when students make such remarks they come with a residual respect for their teachers. Since film journalists aren’t always credentialed, these comments more often are directed at them as a form of dismissal–not just of their interpretations but of the act of interpretation itself. Nobody likes being told what to do, including how to interpret something. Nobody likes feeling (or actually being) hoodwinked. You liked what!?! You know what that is really about don’t you?

Yes, claims about subtexts can be passive-aggressive tweaks at the audience (by the critic or the artist[s]), but they shouldn’t always be dismissed as such.

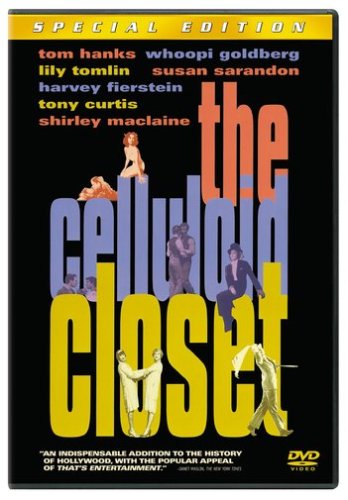

Maybe that is why I have had a soft spot–long before I worked or traveled in circles where such soft spots were acceptable–for The Celluloid Closet, Rob Epstein’s and Jeffrey Friedman’s documentary translation of Vito Russo’s massively influential study of gay representations in cinema. I recently watched Closet again for the first time in many years and I was struck by how thoroughly embedded in our interpretation practice is the acceptance of subtext. Russo’s work is one of those touchstone books that affects the way we look at and talk about films whether we’ve actually read it or not (I have). Success breeds imitation…and push back. But it is hard to push back against something (in this case an interpretation) without acknowledging it exists. And it is nearly impossible to read or watch The Celluloid Closet and deny that subtext has long been a part of our cinematic history.

I would argue that much as with certain terms used in psychoanalytic criticism, “subtext” has entered into the vernacular, broadening its definition and complicating its use. Dictionary.com lists its primary denotation as “an underlying theme in a piece of writing.” Only as a secondary definition does it describe “a message which is not stated directly but can be inferred.” These definitions are somewhat at odds with one another, which is less unusual in the history of word usage than you might think. If “subtext” is simply synonymous with “theme” than too much is hanging on the term “underlying.”

Nor is it entirely satisfactory to suggest that the line between spoken and unspoken, implicit and explicit is always clear in art. Art is dependent upon metaphor, symbolism, analogy. It differs from other forms of discourse precisely in that it seeks to communicate its messages through narrative (or in the case of poetry through figurative language) rather than plain speech. Authors will often use various devices, more or less successfully, to signal ambivalence or even contradiction of explicitly stated themes. When Huck Finn declares, “All right, then, I’ll go to hell” how do we know that Mark Twain is critiquing his society’s morals and not presenting the tragic loss of his protagonist’s way? When Jane Austen’s narrator states that Emma Woodhouse had “very little to distress or vex her” and subsequently tells us of her mother’s early death, nowhere is the theme that jealousy makes us quick to dismiss another’s misfortunes explicitly stated, but it could hardly be more clear.

Artists are skilled at teasing out themes gradually and subtly. Why? Because while few of us enjoy being misled or fooled, fewer still like having opinions or ideas (i.e. themes) shoved down our throat. Witness Alexander Pope’s advice to poets: “Men must be taught as if you taught them not, and things unknown proposed as things forgot.” St. Augustine said that which is sought with more effort is received with more pleasure. We esteem art that rewards careful attention. We like art that tells the truth, but we prefer art that tells it slant so that we might discover it for ourselves.

Where subtlety crosses over into subtext is at the point where the author may not wish everyone to pick up on the theme. In Closet, Gore Vidal confirms the intentional homoerotic subtext included in his uncredited contributions to the Ben Hur screenplay. He is equally emphatic that everyone informed of that angle agreed not to tell Charlton Heston, ostensibly because the star would not have agreed to such a portrayal. Part of what makes Vidal’s claims deliciously ironic is because the first move of the reader who wants to deny subtext is usually to cite authorial intent, but when the author declares his intent, such readers often turn around and reject that criteria, claiming it does not matter what the author meant only what is “in” the text.

Where subtlety crosses over into subtext is at the point where the author may not wish everyone to pick up on the theme. In Closet, Gore Vidal confirms the intentional homoerotic subtext included in his uncredited contributions to the Ben Hur screenplay. He is equally emphatic that everyone informed of that angle agreed not to tell Charlton Heston, ostensibly because the star would not have agreed to such a portrayal. Part of what makes Vidal’s claims deliciously ironic is because the first move of the reader who wants to deny subtext is usually to cite authorial intent, but when the author declares his intent, such readers often turn around and reject that criteria, claiming it does not matter what the author meant only what is “in” the text.

The Ben Hur example is enlightening for another reason. To modern viewers, it seems impossible to imagine that Heston would be unaware that his co-star is treating Judah Ben Hur as an ex-lover. It appears so overt. But to be “subtext” a theme requires something more than being hidden. It needs to exploit the ignorance of one audience or the special knowledge of another. By relying on codes (language, dress, symbols) familiar to one audience but not to all, the subtext strives to remain hidden (historically to avoid reprisals) from one audience while being perfectly clear to the initiated. Of course once the code is made manifest, the preliminary goal is impossible. The disconnect between Heston’s awareness and the modern viewer’s may not be one of acceptance (or not) of homosexuality but awareness of the codes that announce it.

Similarly, as homosexuality becomes more culturally accepted and the broader audience becomes aware of some of the most common signs used to signal it, the possibility of subtext becomes less. Narrowly speaking, Craig Ferguson and Dean DeBlois announcing that Gobber, a Viking in How to Train Your Dragon 2 is gay doesn’t make that character’s utterance that there is “another” reason (besides never finding the right woman) that he never got married a subtext. Ditto J.K. Rowling telling audiences that Dumbledore is gay. What sort of cultural work is done by these proclamations will be discussed in part two of this post, but the very fact that the definitive answer is given by the author suggests that these are hints about initially repressed truths, meant to be attended to not merely by those who will be sympathetic to such readings but by everyone.