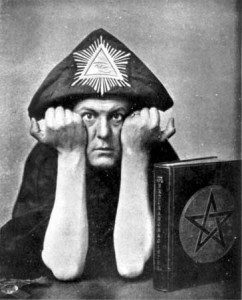

In a previous column, I described the links between an early work of Aleister Crowey’s, White Stains, and the Decadent movement of the late nineteenth-century. Indeed, there are many connections between Crowley’s early poetry and social milieu and literary Decadence. Many people would probably consider Crowley the epitome of a fin de siècle Decadent figure: the Great Beast, the Wickedest Man in the World, writer of erotic poetry and practitioner of strange magicks, translator of Baudelaire, disciple of Swinburne and unveiler of the tomb of Oscar Wilde. Yet there are also areas in which Crowley’s work and philosophy are not at all Decadent, according to the notion of Decadence meant by the literary term.

Hargrave Jennings: A Source of Crowley’s Sex Magick

Crowley’s understanding of sex and sex magic is one of these areas. Crowley, of course, received his early magical training in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn—but, although sometimes a controversial issue, it is generally agreed that the classical version of the Order did not contain any form of sex magical teachings, either in theory or in practice. Crowley developed his ideas about sex through personal inclination, reaction to his puritanical Victorian Protestant upbringing, and his later involvement with Ordo Templi Orientis.

Crowley was also heavily indebted to the curious work of Hargrave Jennings, an esoteric philosopher and scholar of religion who is considered a saint in Crowley’s Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica. Jennings’ The Rosicrucians, Their Rites and Mysteries is included on the A∴A∴ reading list. As Tau Apiryon explains,

The theory of Rosicrucianism set forth in The Rosicrucians revolves around a belief that all religions originated in the primitive worship of the principle of Light or Fire as the animating force of the universe, which is represented by the sun in the heavens and by the phallus in the physical world.

Many of Jennings’ ideas on sexuality, Rosicrucianism, and phallic worship made their way into Crowley’s Thelemic religious system, overlaid with Golden Dawn-inspired Egyptian Godforms and Neo-Buddhist philosophical ideas. Anyone even remotely acquainted with Thelemic doctrine or the Creed of Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica can see the resemblance between Jennings’ explication of phallicism and Crowley’s cosmology: the notion of the sun as the primary object of cult worship, and the phallus as “the sole viceregent of the Sun upon Earth,” the representative of the “creative and life-giving Fire as it manifests itself in living beings who dwell on the surface of this planet.”

Helena and Tau Apiryon are careful to note that it is not exactly the literal, physical penis that is meant by the use of “Phalle” in rituals like the Gnostic Mass and the Star Ruby: “the name ‘PHALLUS’ or ‘PHALLE’ should not be confused with the word ‘penis,’ although the penis does serve as an ancient, yet imperfect, symbol for the PHALLUS.”

According to them, phallicism in this usage “does not refer to penis-worship, but to the worship of the Generative Power—a Power which dwells in sexually mature individuals of both sexes.” This idea is verified in Jocelyn Godwin’s account of Jennings in The Theosophical Enlightenment, who, according to Godwin, used the term “phallicism” to refer to the worship of both the cosmic phallus and the yoni of female polarity. Godwin concludes,

[Jennings’] theory of sexual symbolism as the place where all religions and mythologies unite has the natural corollary that human sexual intercourse, along with the parts of the body concerned, is nothing shameful or indecent, but a replication in the microcosm of the macrocosmic act. (Godwin, 272)

Again, the parallels here with Thelemic doctrine should be obvious: the sex act as a microcosmic image of the primary macrocosmic act, described by Crowley as the interplay of Nuit and Hadit, the constant copulation of the Star-Goddess of infinite space with no circumference with the infinitely concentrated point—an ecstatic cosmogonic act which produces manifest reality. As Crowley rhapsodizes in Liber Aleph: “All is a never ending Play of Love wherein our Lady Nuit and her Lord Hadit rejoice.”

Helena and Tau Apiryon conclude their discussion of the CHAOS article of the Creed of Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica by quoting a line of Crowley’s cited by Israel Regardie in his The Eye in the Triangle: “When you have proved that God is merely a name for the sex instinct, it appears to me not far to the perception that the sex instinct is God.” It is likely that Hargrave Jennings would agree.

Univocal Phallicism vs. Analogical Mysticism

Of course, mainstream scholars and occult historians, such as A.E. Waite, wholly rejected Jennings’ theories, either because of their questionable historicity, or out of a sense of Victorian “decency.” Even with the caveat that phallicism of this sort does not refer to simple “penis-worship” but a more sophisticated understanding of the cosmic generative power, Jennings and Crowley elevate human sexuality to a degree of importance that is very different than the understanding of sexuality professed by mainstream Christianity and other exoteric religions.

Theologically speaking, Jennings and Crowley’s phallicism can be categorized as a univocal understanding of language and ontology. Univocity of being refers to the concept that words describing the properties of God mean the same thing when applied to created objects such as people or things, even if the degree meant is vastly different. In other words, if I describe my cat Laylah as good, this is the exact same sort of goodness as I mean when I describe God as good—it’s just that God is good to a much higher degree than my cat (Laylah might disagree with this assessment).

Phallicism proposes that the constant sexual interplay of polarized cosmic forces—Nuit and Hadit, to use Crowley’s terms—produces manifest reality, and that this interplay is sexual in the same sense as intercourse between two human beings is sexual—just to a vastly different degree. This is why the Sun, the solar representative of this interplay, is worthy of adoration, and why the phallus, or the generative power “which dwells in sexually mature individuals of both sexes,” is the “vicegerent of the Sun upon Earth.” This is also why physical sex magick is an integral part of Crowley’s program for personal spiritual attainment, and why he can make seemingly bizarre statements such as “The industrial use of Semen will revolutionize human society” (diary entry 8 August 1923).

Or, to quote a contemporary source on the Thelemic system, David Shoemaker–in his Living Thelema–proclaims that “the divine and the ecstatic are one“; the practice of sex magick is described as a “gradual process … of identifying sexual ecstasy with divinity itself and, conversely, identifying divinity with ecstasy” (ch. 14).

Of course, the univocity of being is a doctrinal truth for many late medieval nominalist thinkers, and is usually adhered to by Calvinist Protestant theologians—which might account for its ready acceptance by a figure like Crowley, who grew up in a thoroughly Calvinist religious context.

Yet it is not the traditional doctrine of many forms of mystical Christianity, especially of the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, or Anglo-Catholic varieties. These traditions instead emphasize the analogy of being—the notion that when I say my cat is good, it is only an analogous statement to the statement that God is “good.” In other words, God’s goodness is not only a matter of degree; since God is transcendent, human concepts like goodness can only ever analogously apply to God, and the opposite statement—God is not good—must be equally true. This is the basis for the negative theology of thinkers like Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, whose The Mystical Theology lies in the background of a vast amount of medieval and modern Christian mystical thinking.

Sacred sexuality is a core element in the spirituality of many Christian mystics, stemming from an allegorical reading of the Biblical Song of Songs as a description of the mystical marriage between the Bridegroom, Jesus Christ, and the Bride, the Church or the soul of the individual Christian. Figures like St. Teresa of Ávila experienced this union in highly physical, even sexual forms, as a kind of religious ecstasy. Examples of this phenomenon could (and do!) fill whole tomes with rhapsodic language just as orgasmic as the richly sensual verses of The Book of the Law.

But the distinction between analogy of being and univocity of being is very important, in order to avoid reductive conflations of different religious and mystical traditions (a sadly common mistake among many in the occult community). The ecstasy of a Christian mystic experiencing union with God finds a valuable analogy—the symbol par excellence, really—in the example of human sexual union. But it is not the same thing. This is not a matter of degree, but a matter of kind—the ecstasy of a mystic is a different kind of ecstasy altogether from human sexuality, which serves as an analogy that must eventually be transcended.

Sexuality and Decadence

What does all of this have to do with the Decadent Movement? There is a “critical difference” between human sexuality and divine union, and for Christians this is a necessary truth to understand. As queer theologian Elizabeth Stuart explains, human sexuality cannot hold “the divine without remainder.” For all of their exquisite failures, the Decadents understood this truth, and Crowley did not. The Decadent obsession with sexuality always included an air of decay, an “exquisite appreciation of pain, exquisite thrills of anguish, exquisite adoration of suffering … a double ‘passion,’ the sentiment of repentant yearning and the sentiment of rebellious sin,” to use the words of Lionel Johnson. The Decadent careened from the brothel to the confessional, from the music hall to morning Mass. Johnson’s “To a Passionist” dramatizes the Decadent spiritual dilemma in poetic form:

Clad in a vestment wrought with passion-flowers;

Celebrant of one Passion ; called by name

Passionist: is thy world, one world with ours?

Thine, a like heart? Thy very soul, the same?Thou pleadest an eternal sorrow: we

Praise the still changing beauty of this earth.

Passionate good and evil, thou dost see:

Our eyes behold the dreams of death and birth …Canst thou be right? Is thine the very truth?

Stands then our life in so forlorn a state?

Nay, but thou wrongest us: thou wrong’st our youth,

Who dost our happiness compassionate.And yet! and yet! O royal Calvary!

Whence divine sorrow triumphed through years past:

Could ages bow before mere memory?

Those passion-flowers must blossom, to the last.

Many Decadents, even those who identified in ways we would today label queer or kinky, converted to strict forms of Roman or Anglo-Catholicism, a phenomenon documented by Ellis Hanson in his groundbreaking study, Decadence and Catholicism. This is because “Decadent writing is often a literature of Christian conversion, but a conversion that never ends, a continual flux of religious sensations and insights alternating with pangs of profanity and doubt” (10). The religious Decadent “oscillated between extremes of shame and grace, sexual indulgence and extreme piety, re-enacting his conversion over and over again in a Christian narrative of sin and redemption” (12). Decadents found Catholicism to be “the odd disruption, the hysterical symptom, the mystical effusion, the medieval spectacle, the last hope of paganism, in an age of Victorian puritanism, Enlightenment rationalism, and bourgeois materialism … [the Decadents] found in the Church a volatile eroticism that was not necessarily an affront to Catholic belief” (Hanson, 26).

Karmen MacKendrick, in her work Counterpleasures, also describes such a “volatile eroticism” in the context of Catholic belief through her examination of the late ancient ascetic movement, which she compares to modern-day BDSM and the literary work of the Marquis de Sade. In her essay “Carthage Didn’t Burn Hot Enough,” a queer theological reading of St. Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions, MacKendrick explains that Augustine did not convert to Christianity in order to escape erotic love, but because human erotic love wasn’t hot enough. One metaphor used by Augustine was that, while, say, a strip-tease given by a human being has to come to an end, God’s sensual unveiling continues forever, as even those who have attained the Beatific Vision can never reach complete union with the transcendent, ineffable Godhead. The mystic experiencing divine ecstasy is consumed in a conflagration that never ends.

MacKendrick writes, “Full comprehension—of God or by God—is loss of distinction, fire to the point of melting-into” (216). So far, this has a lot in common with many statements on divine union in Liber AL: “There is the dissolution, and eternal ecstasy in the kisses of Nu” (II.44). Crowley would utilize the techniques of sex magick to achieve such ecstasy. Yet Augustine’s understanding of mystical union is analogical, not univocal—it ultimately must transcend human sexual union, which remains, as the Decadents understood, under a “double passion” of repentant yearning and rebellious sin, not divine fulfillment. For, as MacKendrick explains,

Only God even holds—or, as I suspect, is—the promise of burning that hot, a promise that never precisely defines what it offers, made in the constant uprising of desire. The problem with Carthage [Augustine’s home town, and the site of his early sexual exploits] is not, was never, that it burns. Nor is it that its burning is a distraction from higher pursuits. Carthage simply did not burn hot enough; all of the desires aroused there can be satisfied, and Augustine is not after satisfaction. He would burn with the seraphim, until his very self has been fully, unspeakably, burned out. (217)

A Volatile Eroticism

God is not merely a name for the sex instinct, as Crowley suggested, and the human sex instinct is not God. God transcends all names. At the risk of relying too heavily on clips from HBO’s Decadent new series, The Young Pope, this distinction is succinctly (and amusingly) summarized in a conversation between Jude Law’s Pope and his favorite novelist, who asks how a celibate Catholic priest can live without human sexuality, the subject of all of his novels. The Pope answers that “The wise ones long ago understood the degree to which sex as a source of pleasure is overvalued in our society.” When the novelist quips, “Your Holiness, with a few words you have just razed to the ground three-quarters of my literary production. I’ve almost always written about sex as the motor that drives the world,” the Pope responds, “And you were right—but you don’t write about motors that purr, you write about motors that break down continuously …”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxsW_BcRrIwThe eros of God is a motor that purrs. The Decadents, like the ancient ascetics, might have guiltily obsessed over sex but they knew that it was a decaying flower, beautiful in its season but destined to decompose. In Oscar Wilde’s “The Young King,” the regal aesthete of the title learns to replace the fleeting pleasures of earthly luxuries—mired as they are with decay and sin—with the transcendent pleasures of heavenly virtue, which are altogether beautiful in a way that could never be matched by the former.

The Decadents did likewise with human sexuality; Crowley did not. While the Decadents came to an analogical understanding of eros—which required accepting a transcendent, theistic notion of Deity—Crowley remained with a one-track understanding of union. To declare that “There is no god but man” is not only to diminish God, but to relegate man to lesser pleasures and consummations. And the Decadent does not settle for anything but the highest of ecstasies.

—

If you enjoyed this article, check out my new personal blog, The Light Invisible, for more pieces on Christian esotericism.

Patheos Pagan on Facebook.

the Agora on Facebook

The Blooming Staff is published on twice monthly on Tuesdays here on the Agora; follow it via RSS or e-mail!

Please use the links to the right to keep on top of activities here on the Agora as well as across the entire Patheos Pagan channel.