A few weeks ago I re-read Robin Corak’s Reclaiming Medusa. Like Robin, I’ve found myself mulling over Medusa’s mythologies and examining them through the lens of female empowerment and, more broadly, empowerment of the oppressed.

The Short Story

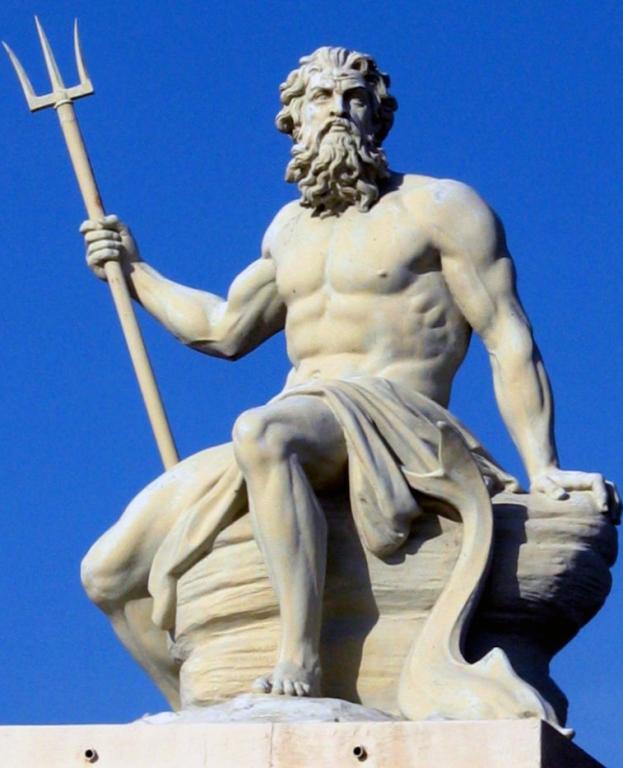

The shorthand of the story most of us remember is this: Medusa was a priestess at one of Athena’s Temples. Poseidon sees her, desires her, and assaults her. Athena then punishes Medusa for defiling Her Temple by giving Medusa a hideous aspect and a head full of snakes that can turn any man who looks upon her into stone.

Some time later, King Polydectes gives Perseus the task of cutting Medusa’s head off. Perseus receives all kinds of help from other gods (sandals, a highly polished shield) to achieve this quest, sneaks up on Medusa while she’s sleeping and lops off her head, bags it, uses it to smite hordes of enemies, and brings it back to Athena, who decorates her warrior’s shield with it.

Athena afterwards placed the head in the centre of her shield or breastplate. There was a tradition at Athens that the head of Medusa was buried under a mound in the Agora. (Paus. ii. 21. § 6, v. 12. § 2.) Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

A Closer Look

When many of us examine Medusa’s story, we can’t escape the theme of powerlessness in which it has its beginning. She’s one of three sisters (the Gorgons), two of whom are immortal. Medusa is mortal, less empowered. In some tellings of her story she is described as having gloriously golden locks of hair, and is so beautiful that every man who looks upon her wants to possess her. Athena punishes her because Medusa has dared to compare her beauty to Her own:

“It is affirmed by some that Medousa (Medusa) was beheaded because of Athene (Athena), for they say the Gorgon had been willing to be compared with Athene in beauty.” Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2. 46 (trans. Aldrich) (Greek mythographer C2nd A.D.)

The more familiar of her mythologies, however, tell us that she was punished because of Poseidon’s assault:

“[Medousa (Medusa)] was violated in Minerva’s [Athena’s] shrine by the Lord of the Sea (Rector Pelagi) [Poseidon]. Jove’s [Zeus’] daughter turned away and covered with her shield her virgin’s eyes. And then for fitting punishment transformed the Gorgo’s lovely hair to loathsome snakes.” Ovid, Metamorphoses 4. 770 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

And make no mistake about it, it’s not like Medusa come-hithered Poseidon there on the beach. Poseidon pretty much felt like if he wanted “it” (and I say “it” because she was an object to possess) he could have it:

“Neptune [Poseidon], wert thou mindful of thine own heart’s flames, thou oughtst let no love be hindered by the winds–if neither Amymone, nor Tyro much be praised for beauty, are stories idly charged to thee, nor shining Alcyone, and Calyce, child of Hecataeon, nor Medusa when her locks were not yet twined with snakes, nor golden-haired Laodice and Celaeno taken to the skies, nor those whose names I mind me of having read. These, surely, Neptune, and many more, the poets say in their songs have mingled their soft embraces with thine own.” Ovid, Heroides 19. 129 ff (trans. Showerman) (Roman poetry C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.)

“Soft Embraces” or “Resistance is Futile”?

Christobel Hasting’s The Timeless Myth of Medusa, a Rape Victim Turned Into a Monster explores how the interpretations of Medusa’s story have evolved through the ages. Steeped in a male point of view from the very beginning, her earliest stories show us how disempowered women have been. Medusa’s so sidelined that she’s not even at the center of her own story:

Popular retellings of the myth, however, focus on what happens next [after Athena punishes her]—and Perseus the starring role. […] It’s through this male-centered hero narrative that Medusa became shorthand for monstrosity. (Christobel Hasting, The Timeless Myth of Medusa, vice.com, April 2018)

Elizabeth Johnstone, in her ‘The Original ‘Nasty Woman’ extends this thought:

“Similarly, feminist scholars like Marija Gimbutas re-read the myth of Medusa as a beheading of early matriarchal societies by Greco-Roman culture. According to this interpretation, Neptune’s rape of Medusa and Perseus’s subsequent beheading of her represent the same effort to legitimize male privilege by muting female authority.” (The Atlantic, November 2006)

Examining Medusa in terms of the male gaze renders her powerless from beginning to end, objectifies her to the point of being a mere vessel knocked around (and up) for most of her life and ultimately betrayed and used by the very goddess to whom she had dedicated her life as a Temple priestess. How does Medusa’s story change, though, when viewed through a feminist lens?

Punishment or Present?

As I read different feminist reinterpretations of Medusa’s story, I ran across a piece by McKenzie Schwark, Snake Eyes: The Power to Turn the Patriarchy into Stone. She writes:

In examining the myth of Athena and Medusa further, the story also seems to be a suggestive fable, slyly teaching women how to look out for and protect one another in a society dominated by men, where rape is a constant threat. Athena was aware of Poseidon’s hunger for Medusa and knew of Medusa’s vow of celibacy. What if Athena’s curse on Medusa wasn’t a punishment at all, but an act of kindness and protection? (April 2019, bitchmedia.org)

Feminist interpretations of Medusa’s story show us ways to reclaim her as a modern protectress against patriarchal hierarchies seeking to disempower our efforts and silence our voices. Athena gives Medusa the gift of not only deflecting/reflecting the male gaze (or, stated another way, of speaking Truth to Power); in a society structured and rooted in male-specific values (and yes, I mean men legislating what happens to women’s bodies) Athena gives Medusa a shield that allows her to fight the patriarchy fearlessly.

This feminist viewpoint also helps to resolve the end of Medusa’s story, when Athena affixes her severed head to her own shield. While Perseus’ use of her head as a weapon against his enemies represents her further objectification as a Thing to be used solely for the benefit of a man, Athena’s use of Medusa’s head can be understood in terms of transcendence and as an icon of empowerment. “Look, upon my shield,” Athena seems to say, “and remember I offer protection.”

Transformation

Medusa, then, is transformed. When any of us, regardless of genders, seek to change a system of oppression we are also transformed. Change can be scary, but transformation—the reworking of everything we know and everything we know ourselves to be—is terrifying. When we step outside of the system we’re subject to vilification, ridicule, and intense pressure to fall back into line and conform. The majority will try any tactic—belittlement, shaming, othering, outing—to maintain the status quo, no matter how inequitable that status quo is.

Interpreting Medusa’s story through a feminist lens shows us the lengths we may have to go in order to step outside of the system and effect real, tangible change. Those battles may so alter who we are at our core that we may no longer recognize who we used to be before we sought to change the system. Perhaps we look in the mirror and are momentarily frozen in shock at the justice warriors we’ve had to become.

And then we take up Athena’s shield, embossed with Medusa’s terrifying head, and go back out there to fight against injustice once more time. And one more time again, and yet again still. As many times as we have to plus one more.

Because we’re not here to protect the status quo; we’re here to protect the rights of those who have been demeaned and dehumanized, those who have been erased and silenced by the status quo.

And we’re not afraid of being as terrifying as we need to be to make that happen.

Additional Sources

You can hear more of The Corner Crone during her Moments For Meditation on KPPR Pure Pagan Radio on TuneIn.