The AmericanNeopaganism.com website which I maintain will be taken down next month. I’ve maintained it for several years now, and it’s been about a year since I made any changes to the site. All of my writing energy has gone into this blog. I’ve decided to let the domain lapse until I figure out what direction I want to take it.

When I first came to Neopaganism, it was through books. And when I encountered the real thing, I was, frankly, disappointed. Somehow, in the process of learning about Neopaganism, I had imagined something which really did not exist — a celebratory Neopagan religion without any of the trappings of esotericism or practical magic. When I left my books and made my foray into the Neopagan community, I was disappointed to discover that “Neopaganism” was generally perceived as an umbrella term and not a tradition in its own right. When asked what your tradition wasm you could not just say “Neopagan”. And I was disappointed to discover that what was perceived as “Neo-Pagan” was really Neo-Wiccan — and many Pagans seemed oblivious to this fact. Since I did not identify as witch or Wiccan (or druid or shaman for that matter), I was at a loss where to go.

So I set about to stake out some territory on the religious landscape for myself — and the American Neo paganismwebsite was born. I specifically had the goal of defending the proposition that American Neopaganism was a tradition in its own right, distinct from Wicca, as well as from Pagan Reconstructionist traditions. In the process, I discovered that I was both wrong and right. In this post, I am going to outline what I was hoping to find. And in my next post, I will discuss how and why I did not find it. I will also discuss some groups that come (or came) pretty close.

Specifically, when I went looking for a Neopagan community, I was looking for a tradition which was:

(1) eclectic — meaning non-traditional and non-reconstructionist,

(2) open — meaning non-initiatory, and

(3) celebratory — meaning non-esoteric and eschewing practical magic.

In short, I was looking for a Neo-Paganism with all the Wicca taken out of it. In my studies, I felt I had had identified something unique, something which I called “Neopagan” — something which I felt was distinct from, and even antithetical to, the esotericism and magic which are part of Wicca.

For clarity sake, I should say that, by “esotericism”, I follow Wouter Hanegraaf in referring to a nexus of related quasi-religious movements, sometimes called the “Western Esoteric Tradition” or the “Western Mystery Tradition”, and including Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Kaballah, ceremonial magic (or “magick”), astrology, alchemy, tarot, spiritualism, and Theosophy, and the philosophies of Jacob Bohme, Franz Mesmer, Emanuel Swedenborg, Helena Blavatsky, Rudolph Steiner, and Aleister Crowley. The common trait among these movements is the notion that esoteric knowledge is secret or hidden and available only to a small elect group and only through intense study. This knowledge often takes the form of a system of hidden correspondences between levels of reality. “Esotericism” is often used interchangeably with “occultism”, but I believe the latter category to be broader.

By “Wicca”, I refer to an initiatory mystery religion, which blends Golden Dawn ritual forms with witchcraft folklore derived from Charles Leland and Margaret Murray. Indicia of a Wiccan tradition are: duotheism, gender polarity, eight seasonal “sabbats”, ritual drawn from ceremonial magic including casting a magic circle, calling the quarters, and “raising energy”, and the practice of practical magic. Note: I use the term “Wiccan” even for those people who identify as “Witches” and not “Wiccan”, if they fall into the category as described above.

I was uncomfortable with both practical magic and esotericism because I felt they were incompatible with my commitment to empiricism. But also the notion of magical control of nature seemed to me to be antithetical to the Neopagan attitude of reverence of and cooperation with nature. My vision of a non-esoteric Neopaganism was best expressed in Robert Ellwood and Harry Partin’s Religious and Spiritual Groups in Modern America:

“The unifying theme among the diverse Neo-Pagan traditions is the ecology of one’s relation to nature and to the various parts of one’s self. As Neo-Pagans understand it, the Judaeo-Christian tradition teaches that the human intellectual will is to have dominion over the world, and over the unruly lesser parts of the human psyche, as it, in turn, is to be subordinate to the One God and his will. The Neo-Pagans hold that, on the contrary, we must cooperate with nature and its deep forces on a basis of reverence and exchange. Of the parts of man, the imagination should be first among equals, for man’s true glory is not in what he commands, but in what he sees. What wonders he sees of nature and of himself he leaves untouched, save to glorify and celebrate them.”

In this view, esotericism and practical magic were not Neopagan, but rather part and parcel of the legacy of the Enlightenment goal of dominating nature.

As a result, I took issue with the common perception of Neopaganism as the “exoteric” circumference of a circle at which Wicca is the “esoteric” center. In this view, Neopaganism is a generic form of Wicca — a kind of Wicca lite. But I believed that Neopaganism had more than enough substance to be a tradition in its own right, and one which could be and should be distinguished from Wicca. In the course of my reading, I came across a few writers who agreed.

In Wicca and the Christian Heritage, Jo Pearson questions whether Wicca can even be considered a form of Neopaganism. She writes: “In many ways initiatory Wicca can be regarded as existing on the margins of Paganism.” In New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought, Wouter Hanegraaff observes “that Wicca is a neopagan development of traditional occultist ritual magic, but that the later movement is not itself pagan.”

Robert Ellwood and Harry Partin drew the same conclusion earlier in their Religious and Spiritual Groups in Modern America. Ellwood and Partin broke Neopaganism into the magical groups, influenced by the model of the Order of the Golden Dawn, the O.T.O., and Aleister Crowley, and the nature oriented groups. The magical groups, they wrote:

“are the more antiquarian; they love to discuss editions of old grimoires, and the complicated histories of groups an lineages. They delight in precise and fussy ritualism, though the object is the evocation of intense emotional power […]

“The pagan nature-oriented groups are more more purely romantic; the prefer woodsy setting to incense and they dance and plant trees. They are deeply influenced by Robert Graves, especially his White Goddess. They are less concerned with evocation than celebration of the goddesses they know are already there. The mood is spontaneous rather than precise, though the rite may be as beautiful and complex as a country dance. […]

(Partin and Ellwood offered Feraferia as an example of the latter group.) Interestingly, Partin and Elwood described Wicca as being “in the middle between magic and nature-oriented groups.” Elsewhere, Ellwood distinguished “occult groups”, which “offer initiation into expanded consciousness through a highly structured production of internal experiences and impartation of knowledge”, from “neopagan groups”, which “promote a new vision of man’s relation to nature, the archetypes of the unconscious, and the passions”.

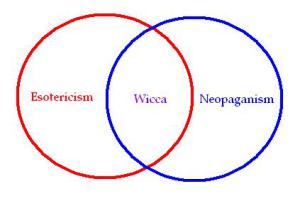

I suggest that it might be helpful to think of Neopaganism and esotericism as two circles circumscribing different cultural phenomena with overlapping circumferences. Traditional Wicca would fall within the overlapping area, whereas Neopaganism would fall outside of the circle of esotericism.

It was this celebratory and nature-oriented side of this picture which I want to extract from the esoteric side in which Wicca was (at least partially) rooted.

I also wanted to distinguish Neopaganism from Reconstructionist Paganism (or retro-Paganism). While drawing inspiration from numerous ancient traditions and reconstructions of ancient traditions, Neopaganism is consciously and unapologetically eclectic. It does not aim to reconstruct a (paleo-)pagan past, but rather to construct a Neo-Pagan present and future.

Various names have been suggested by others for this celebratory form of Neopaganism, including “non-initiated Paganism” (Tanya Luhrmann), “non-aligned Paganism” (Jo Pearson), “exoteric Paganism (Vivianne Crowley). I chose the term “American Neopaganism” following both Aidan Kelly and James Lewis use of the term “American Tradition” to describe the Pagan Way. (More on that in the next post.)

The use of the prefix “Neo-“ was intended to distinguish American Neopaganism both from modern forms of paganism (which include Hinduism, Voudun, and others) and from modern reconstructions of ancient paganisms (such as Druidry, Heathenry, and others). Whether it dates to the 1967 organization of the Church of All Worlds and Feraferia or the 18th century Romantic Movement, Neopaganism is still a relatively new religion in comparison to the world’s religions. In addition, Neopaganism, as I understand it needs, to be distinguished from ancient paganisms, which it rarely resembles (as well as from modern reconstructions of ancient aganisms). Ancient pagans were mostly hard (or radical) polytheists, not Jungian polytheists, and not pantheists either (with a few exceptions like the Stoics). The morality of ancient pagans is also distinguishable from that of modern Neopagans, whose morality is the product of the Enlightenment and Liberalism.

The modifier “American” was intended to distinguish American Neopaganism from more nationalistic European forms of Neopaganism, including the 19th century German volkisch movement, northern European heathenry, British druidry, as well as from traditional Wicca, which was originally conceived as a revival of an ancient British religion.

The “American” modifier was also intended as a recognition that Neopaganism really a product of the American Sixties counterculture. Sarah Pike, in her book Witching Culture, dates Neopaganism to the founding of the Church of All Worlds and Feraferia in 1967. While it was undoubtedly influenced by Wicca, I argued that American Neopaganism was historically and theologically distinct from Wicca. In my view, the intellectual and spiritual grandfather of American Neopaganism was not Gerald Gardner, but Robert Graves. The White Goddess had only a minor influence on traditional Wicca, but was the inspiration behind most American forms of Neopaganism, including the Pagan Way movement, the Church of All Worlds, Feraferia, and NROOGD. These and other American groups arose in the context of the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s and integrated Graves’ mythology with the feminist spirituality movement (especially the Goddess movement), religious ecology (or nature religion), and Jungian psychology. It was to those traditions that referred when I wrote about “American Neopaganism”.

I was to discover, however, that it was separating the influence of Wicca from Neopaganism was more difficult than I had hoped. And it is for that reason, perhaps, that occultism and practical magic now seem to be inseparable from Pagan culture. And that is the subject of my next post.