Neo-Paganism is a nature religion which, like other nature religions, perceives nature as both sacred and interconnected. From this perspective, humans in the developed world have become tragically disconnected from nature, which has been desacralized in both thought and deed. Healing this rift is possible only through a profound shift in our collective consciousness. This constellation of ideas can be called “Deep Ecology”. This is the third in a 5-part series about some of “fruits” of Deep Ecology. This essay was originally published in parts at Neo-Paganism.com.

When holy water was rare at best

It barely wet my fingertips

But now I have to hold my breath

Like I’m swimming in a sea of it

It used to be a world half there

Heaven’s second rate hand-me-down

But I walk it with a reverent air

‘Cause everything is holy now— Peter Mayer, “Holy Now” (song)

Pantheism means “All (pan-) is God (theos)”. Pantheism is the belief that God/dess is not remote or separate from nature, but immanent within it. According to David Waldron, pantheism, the perception of divinity as manifest in the physical world, is the quintessential component of Neo-Pagan identity.

Pantheism may be understood in contrast with transcendental theism which posits a God who is not a part of the world or creation, a God who is radically “other” or transcendent. Monotheism is an example of transcendental theism. The logical outcome of transcendental theism is either a fundamental dualism, in which God and the world are radically separate and humankind is alienated from God, or a monism which conceives of the world as unreality or illusion. Most forms of Christianity fall into the former category, while some forms of Buddhism and Hinduism are examples for the latter. Both of these propositions are unacceptable to Neo-Pagans, who view the world as neither fallen nor illusory.

Neo-Pagan activist and author of The Spiral Dance, Starhawk, writes:

“[O]ur primary understanding [is] that the Earth is alive, part of a living cosmos. What that means is that spirit, sacred, Goddess, God–whatever you want to call it–is not found outside the world somewhere–it’s in the world: it is the world, and it is us. Our goal is not to get off the wheel of birth nor to be saved from something. Our deepest experiences are experiences of connection with the Earth and with the world.”

Starhawk explains how belief in a pantheistic deity is unnecessary:

“People often ask me if I believe in the Goddess. I reply ‘Do you believe in rocks?’ It is extremely difficult for most Westerners to grasp the concept of a manifest deity. The phrase ‘believe in’ itself implies that we cannot know the Goddess, that She is somehow intangible, incomprehensible. But we do not believe in rocks we may see them, touch them, dig them out of our gardens, or stop small children from throwing them at each other. We know them; we connect with them. In the Craft, we do not believe in the Goddess we connect with Her; through the moon, the stars, the ocean, the earth, through trees, animals, through other human beings, through ourselves. She is here. She is within us all. She is the full circle: earth, air, fire, water, and essence — body, mind, spirit, emotions, change.”

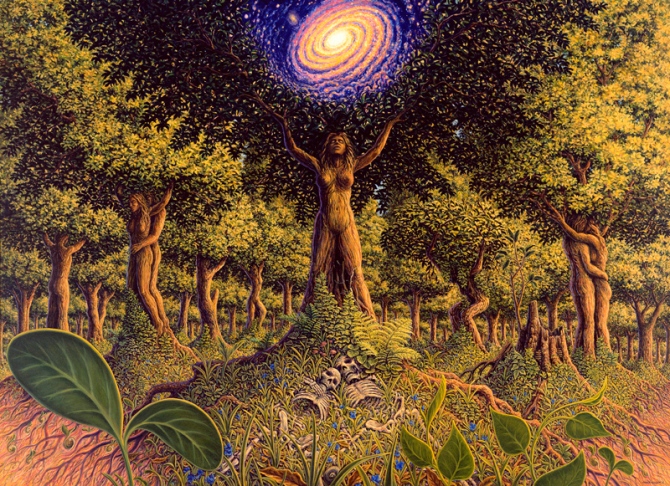

The image of the Goddess as Earth Mother is one of the most common ways that Neo-Pagans express their pantheism. For Neo-Pagans, the world is either contained within the womb of the Goddess and, hence, a part of her body, or else born of the Goddess, bodied forth from her own physical substance and still dependent upon her for sustenance.

The image of the Goddess as Earth Mother is one of the most common ways that Neo-Pagans express their pantheism. For Neo-Pagans, the world is either contained within the womb of the Goddess and, hence, a part of her body, or else born of the Goddess, bodied forth from her own physical substance and still dependent upon her for sustenance.

The meaning of the Goddess as Mother is that the divine is creative. But unlike the creator God of the monotheisms, the Goddess’ creativity is organic, a function of what she is, rather than something she does. It is through her body that she creates. Two thousand years ago, the Greek historian Plutarch recognized this truth (although he used masculine language instead of feminine language):

“The work of a maker — as of a builder, a weaver, a musical-instrument maker, or a statuary — is altogether distinct and separate from its author; but the principle and power of the procreator is implanted in the progeny, and contains his nature, the progeny being a piece pulled off the procreator. Since therefore the world is neither like a piece of potter’s work nor joiner’s work, but there is a great share of life and divinity in it, which God from [her]self communicated to and mixed with matter, God may properly be called [Mother] of the world — since it has life in it.”

Not all women are mothers, or want to be mothers, and pregnancy and birth are not the only forms of creativity open to women. However, everyone — female and male — has had a mother, and we are acculturated to desire a good mother. As Stephen Benko has observed in his study of the pagan roots of Mariology:

“Our earliest memories are likely to come from our mothers; our concept of life is inseparable from that of the womb; our concept of nurturance is female, and everybody has some understanding of the mother-child relationship. … ‘Even if we do not agree with the Jungian idea of a female archetype, all humans understand the mother-infant bond and recognize the related universal symbol of the womb as the mother of life.'”

Rather than being a simplistic prescriptive model for human behavior, the Goddess as Mother draws our attention to how we are immersed in a material world that is radically interconnected. It affirms our bodily reality and relationships with each other and the natural world. Indeed, the word “matter” derives from the Later word for “mother” (mater).