In my recent exchange with Sarenth Odinsson about whether atheists have a conception of the holy (obviously, I think we do), a word came up: “cosmology”. Odinsson implied that atheists have no religion or cosmology:

“The idea of holiness and sacredness cannot exist without a religion and cosmology. … Atheism denies that Gods exist, and in so doing, denies the cosmology They are rooted within. The notion of holiness within an atheist context, therefore, cannot exist.”

As I have written before, I think Odinsson is conflating the question of whether one is theistic with the question of whether one is religious. It is possible to be a religious atheist (practicing religion without a belief in gods), just as it is possible to be a non-religious or secular theist (believing in gods without any religious practice).

But what I want to talk about today is this idea of cosmology. In the quote above, Odinsson seems to conflate theism and cosmology, but in a subsequent post, he admits that they are not the same:

“Most, though certainly not all forms of atheism, reject religious cosmology.”

He thus implies that there is such a thing as an atheist cosmology — and he’s right! There is!

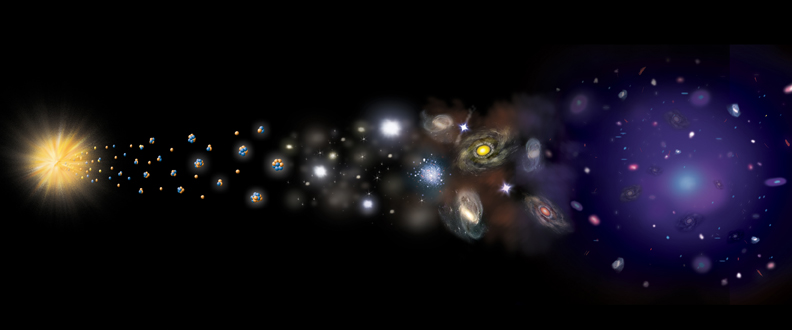

The emerging non-theistic cosmology is called “The Great Story.” It is the 14 billion year narrative of the evolution of the cosmos, the planet Earth, biological life, and human culture.

“Tell me a creation story more wondrous than the miracle of a living cell forged from the residue of an exploding star! Tell me a story of transformation more magical than that of a fish hauling out onto land and becoming amphibian, or a reptile taking to the sky and becoming bird, or a bear slipping back into the sea and becoming whale! If this science-based culture, of all cultures, cannot find meaning and cause for celebration in its very own cosmic creation story, then we are sorely impoverished indeed.” — Connie Barlow

This story has been told in many ways, by Thomas Berry, Brian Swimme, Michael Dowd and Connie Barlow, and others, and it has been called by many names, like “the Universe Story,” “the Epic of Evolution,” and “Big History.”

The Great Story is a cosmology, combining logos (science) and kosmos (a storied universe). It is “scientific in its data, mythic in its form” (Berry and Swimme). It “honors both objective truth and subjective meaning” (Michael Dowd). It “bridges science and religion, fact and value, and it smoothly blends the scientifically objective with the culturally relative” (Russell Merle Genet).

It is a myth, in the best sense of that word, but one that happens to be literally true; it is a narrative that orders our world, helps us understand our place in it, shows us how to live meaningful lives, and enables us to come to terms with our own finitude.

The Great Story teaches us where we came from:

“[E]very one of our body’s atoms is traceable to the big bang and to the thermonuclear furnace within high-mass stars. We are not simply in the universe, we are part of it. We are born from it. One might even say we have been empowered by the universe to figure itself out — and we have only just begun.” (Neil deGrasse Tyson, “The Greatest Story Ever Told”)

“Not only do we live among the stars, the stars live within us,” writes Neil deGrasse Tyson. And if we consider that the ancients believed the stars were gods, then we might say that “not only do we live among the gods, the gods live within us.”

The Great Story teaches the meaning of our existence: We are the universe coming to know itself. And if you are a pantheist, like me, then that means we are also God/dess coming to know Herself.

The Great Story teaches us that there is something greater than ourselves: the evolutionary process of life itself — but it is a greatness that we are a part of and share in the dignity of:

“[W]hen I look up at the night sky, and I know that yes we are part of this universe, we are in this universe, but perhaps more important than both of those facts is that the universe is in us. When I reflect on that fact, I look up- many people feel small, cause their small and the universe is big. But I feel big because my atoms came from those stars.” (Neil deGrasse Tyson).

The Great Story teaches us that we are all connected:

“[T]he very molecules that make up your body, the atoms that construct the molecules, are traceable to the crucibles that were once the centers of high mass stars that exploded their chemically rich guts into the galaxy, enriching pristine gas clouds with the chemistry of life. So that we are all connected to each other biologically, to the earth chemically and to the rest of the universe atomically.” (Neil deGrasse Tyson)

And from these lessons emerges a new “global ethos” (Goodenough), one informed both by the recognition of the uniqueness of our evolved consciousness and by the appreciation of our interconnectedness with all life, an ethic of care for and responsibility to all forms of life.

The Great Story is the response to the reductionist mentality which posits that the more we know about the universe, the less meaning it seems to have. What Maria Montessori said in 1948 about the power of story for children applies with equal force to adults:

“Educationalists in general agree that imagination is important, but they would have it cultivated as separate from intelligence, just as they would separate the latter from the activity of the hand. They are the vivisectionists of the human personality. In the school they want children to learn dry facts of reality, while their imagination is cultivated by fairy tales, concerned with a world that is certainly full of marvels, but not the world around them in which they live. On the other hand, by offering the child the story of the universe, we give him something a thousand times more infinite and mysterious to reconstruct with his imagination, a drama no fable can reveal.”

“The evolutionary epic is probably the best myth we will ever have,” wrote Edward O. Wilson in 1978. It is, without exaggeration, the Greatest Story Ever Told.

It is a sacred story. It is sacred because it imbues the world and its beings with value which transcends their utilitarian usefulness to us. It is sacred because it occupies the same place in our lives which other sacred stories occupy in the lives of other religious people. It is sacred because it inspires humility, gratitude, and reverence.

It is a story that which makes it possible to be both a religious person and a scientific naturalist. As Ursula Goodenough explains, “a religious naturalist is a naturalist who has adopted the epic as a core narrative and goes on to explore its religious potential, developing interpretive, spiritual and moral/ethical responses to the story.” And one form of religious naturalism is Naturalistic Paganism.

The Great Story is my cosmology.

Watch the video: 13.7 billion years of evolution in 85 seconds

For further reading:

- Brianne Swimme, The Universe is a Green Dragon: A Cosmic Creation Story (1984)

- Brian Swimme, The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era (1992)

- Eric Chaisson, Epic of Evolution: Seven Ages of the Cosmos (2008)

- Chet Raymo, When God Is Gone, Everything Is Holy (2008)

- Michael Dowd, Thank God for Evolution (2008)

- Ursula Goodenough, Sacred Depths of Nature (2000)

- Loyal Rue, Everybody’s Story: Wising Up to the Epic of Evolution (2008)