How can we know the dancer from the dance?

— W.B. Yeats

Theism, Pantheism, and Panetheism

In his latest effort to tell the Pagan world why everyone is wrong and he is right, Sam Webster has taken aim an panentheism, the belief that God is both transcendent and immanent. Webster dispatches panentheism in one paragraph explaining that it is “logically untenable” for God to be All and then some.

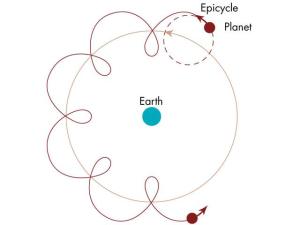

Panentheism represents one of three logical possibilities for describing the nature of God’s (you can substitute “Being” or the “Ground of Being” for “God” here) relation to the world. Either God is “wholly other” than the world (transcendental theism), God is the world (pantheism), or God is both other and the world (panentheism). (Incidentally, polytheists and “pluralist” Mormons don’t really fit any of these categories because the gods they worship are not ultimate Being, but rather particular beings in the universe of beings.) Webster tries to make the case for pantheism in his post.

Each of these options — transcendental theism, pantheism, and panentheism — have their problems. In his rush to get to the one-and-only Truth, Webster overlooks these. What I have come to believe is that each of these options is both right and wrong. Or rather, they each tell us something about the nature of God-Being-Ground.

Transcendental theism tells us that God is “wholly other”, A≠B — i.e., the Creator is a completely separate ontological category from creation. The problem this creates is: how does the one interact with the other? The logical outcome of transcendental theism is either a fundamental dualism in which God and the world are radically separate and, consequently, nature (including humankind) is alienated from God, or a monism which sees the world as unreal or illusion. Christianity is an example of the former, and it tries to overcome this problem (mythologically) with the Incarnation. Some forms of Buddhism and Hinduism are examples of a monism which sees the world as maya. Both of these propositions — world as separate from divinity and world as illusion — are unacceptable to most contemporary Pagans, who view the world as neither fallen nor illusory.

Pantheism has its own problems, namely, if the World is God, then why do we need two different words for the same thing. What does it mean logically to say that A=B? In addition, pantheism may imply determinism, to the extent that past, present, and future are seen as one. Finally, pantheism does not explain the human experience of alienation that gives rise to transcendental theisms.

Pan-en-theism is the third option. According to David Ray Griffen, in Sacred Interconnections (1990), panentheism means that “God is not remote and separate from nature, but immanent within it. Yet at the same time God is the unity which transcends it.” Panentheism has been espoused (in various forms) by as diverse thinkers as the Spinoza, Hegel, Meister Eckhart, the Transcendentalists, Teilhard de Chardin, Heidegger, the Process Theologians, contemporary Goddess Thealogians, and many more. See John Cooper, Panentheism: The Other God of the Philosophers. Recognizing the logical problems of both a God that is wholly transcendent and a God that is wholly immanent, panentheism tries to strike a balance between the two. Or, if you are feeling less charitable, you might say that it doubles down on the logical inconsistency by not taking a position: A=B≠B.

Panentheism and pantheism both share the proposition and the world and God are in some sense “one”. However, panenthism differs from pantheism and resembles transcendental theism in that it preserves the “otherness” of God. It is significant that pantheists often (mis-)understand panentheism as collapsing into transcendental theism, while transcendental theists see panentheism as just another form of pantheism. However, panentheism is distinguishable from both philosophies, even as it tries to preserve the insights of both.

Panentheism affirms that, the world is “in” God, but God is not entirely identical with the world. That is, God is not limited to the world; God is also the wholeness which transcends the world. This wholeness includes not only the manifest world, but the “unmanifest” or latent potentialities which have not been real-ized in nature. The philosopher Hegel illustrates this through analogy to the growth of a plant in his opus, The Phenomenology of Spirit:

“The bud disappears in the bursting-forth of the blossom, and one might say that the former is refuted by the latter; similarly, when fruit appears, the blossom is shown up in its turn as a false manifestation of the plant and the fruit now emerges as the truth instead. These forms are not just distinguished from one another, they also supplant one another as mutually incompatible. Yet at the same time their fluid nature makes them moments of an organic unity in which they not only do not conflict, but in which each is as necessary as the other; and this mutual necessity alone constitutes the life of the whole.”

In this analogy, the world is the blossom/fruit and God is the “life of the whole” which includes both the blossom and the fruit. Thus, panentheism thus tries to preserve the concept of the “otherness”, but transforms it into an otherness which, paradoxically, does not exclude, but includes.

I’m not going to argue that panentheism is superior to transcendental theism or pantheism. Here’s what I want to say about these three options: People have been arguing about this question for literally millennia, and will continue to do so. The history of Christianity can be seen as a pendulum swinging between the poles of transcendence and immanence. See Stanley Grenz & Roger Olsen, 20th Century Theology: God and the World in a Transitional Age (1992). And Indian philosophy is at least as rich in nuance on this issue. And while I lean in the direction of panenthism (and pantheism when in a pinch), I think all three deserve some respect.

But I do want to try to explain here how I understand panentheism and why I think it is a beautiful idea. I will be speaking here, primarily in mythological, not logical, terms, so this is not a direct response to Webster. If the issue could have been resolved logically, I think we would have done it in 2000 years of Christianity and 3000 years of Indian philosophy, not to mention other traditions. (Ancient Western paganisms seem to have been more concerned with worshiping a multiplicity of gods beings rather than Being as such. Although there were exceptions, like the Stoics and Neoplatonists.) If you’d like a more logical explication of panentheism, I recommend Philip Clayton’s In Whom We Live and Move and Have Our Being: Panentheistic Reflections on the Presence of God in a Scientific World (2004).

Panentheism in Paganism: The Dancer and the Dance

For me, panentheism finds mythological expression in the Neopagan Goddess, who represents the Sacred Whole, and her consort, the god, who represents nature in all its particularity, which includes you, me, the sun, the trees, the rocks, all in this given moment. The relationship between Goddess* and her consort expresses the mystery of diversity within unity. In Joseph Campbell’s words, the Great Goddess is

“the arch personification of the power of Space, Time, and Matter, within whose bound all beings arise and die: the substance of their bodies, configurator of their lives and thoughts, and receiver of their dead. And everything having form or name—including God personified as good or evil, merciful or wrathful—was her child, within her womb.”

Masks of God, Vol 3: Occidental Mythology (1964).

Robert Graves’ mythology provides a historical starting point for the panentheistic Neopagan divinity. Graves’ Triple Goddess is an ever-changing, but never-dying Great Goddess of the cosmos. Quoting Apuleius, Graves’ Goddess declares: “I am she that is the natural mother of all things […] manifested alone and under one form of all the gods and goddesses.” Graves’ god-consort is the son, lover, and ultimately the sacrificial victim of Goddess. The god is born and dies, but Goddess — while she changes from maiden, to mother, to crone, and then to maiden again — is never born and never dies.

Graves’ mythology was adopted by Starhawk and popularized in her book, The Spiral Dance, the title of which is a metaphor for Goddess herself:

“The Goddess is the Encircler, the Ground of Being; the God is That-Which-Is-Brought-Forth, her mirror image, her other pole. She is the earth; He is the grain. She is the all encompassing sky; He is the sun, her fireball. She is the Wheel; He is the traveler. He is the sacrifice of life to death that life may go on. She is the Mother and Destroyer; He is all that is born and is destroyed.”

According to Starhawk’s model, the god is the mortal dancer and Goddess is the immortal Dance.

As John Cooper explains, Starhawk

“locates transcendence in the depths of an immanence in the world. Transcendence in her theology is the primordial unity, the ‘unbroken cycle,’ the Life Force beyond sexual differentiation. This basic reality is ontologically deeper that the polarity of forces that generate all the creatures in the world. It is their source and the context in within which they exist. […] Thus Starhawk affirms all the essential ingredients of panentheism.”

Starhawk likely borrowed the name of her book from the Spiral Dance (also called the “Meeting Dance”) originally performed by the New Reformed Order of the Golden Dawn (NROODG) tradition of Neo-Wicca, with which she associated. Interestingly, in 1972, the original NROOGD coven (the Full Moon Coven) hived off the “Spiral Dance Coven”. Later, another coven hived off called “The Dancer and the Dance Coven”. The NROODG was itself heavily influenced by Robert Graves’ The White Goddess.

Starhawk may also have borrowed the panentheistic conception of Goddess from Frederick Adams. According to Margot Adler, Adams’ (unfortunately-named) “Nameless Maiden” (Adams had a less-than-avuncular preoccupation with divine maidens) “spins a cosmic dance from which all things come into existence, each of them unique and particular.” She is the

“‘transcendent unique,’ the creatrix of all uniqueness. All entities she creates interrelate with her, but never lose their individual essence. Thus she represents polytheistic wholeness as opposed to monotheistic unity. An analogy to this might be a symphony, where each note is differentiated, but the whole is something beyond a ‘unity’.“

Subsumed within pantheistic “transcendental unique” are what Adams calls “the Goddess-given Gods”, which include the Mother, “the Source and Center”, the Son, “creative separation”, the Father, full “particularization”, and the Daughter, “creative return”. Over this four-step movement, or dance, is Adams’ Nameless Maiden who is “the Mysterious Wholeness of the Four which consist in their dynamic separation.” (Unfortunately, I have not been able to corroborate Adler on this point. According to Hans Holzer, Adam’s theology includes a Great Goddess, her son and daughter, Kouros and Kore, seven planetary gods, and lesser spirits, arranged hierarchically.)

Another possible source of of the panentheistic conception of Goddess is the McFarland Dianic tradition, which also was influenced by Robert Graves, and may have influenced Starhawk in turn. The Dianic witchcraft tradition, now called the McFarland Dianic tradition (MDT) to distinguish it from Z. Budapest’s feminist Dianic tradition, was created in 1971 by Morgan McFarland and Mark Roberts. Unlike both traditional British Wicca, which viewed divinity as essentially a polarity of male and female divinities, and feminist Dianic witchcraft, which viewed divinity monotheistically as a parthenogenic female, the McFarland Dianics occupied a middle ground, viewing divinity in terms of an immortal Creatrix and her mortal male consort.

Margot Adler describes the group’s beliefs thus:

“The Goddess is seen as having three aspects: Maiden[…], Great Mother, and Old Crone, who holds the door to death and rebirth. It is in her second aspect that the Goddess takes a male consort, who is as Osiris to Isis. To show this relationship, [McFarland] Dianics quote a phrase attributed to Bachofen: ‘Immortal is Isis, mortal her husband, like the earthly creation he represents.’ Thus there is a place for the God, but the female as Creatrix is primary.”

From the no longer active McFarland Dianic website [http://crystalillumination2012.org/]:

“In the McFarland Dianic Tradition the Goddess was never born, and She never dies. She always was, is, and always will be. She is the fertile Void at the Center from which the universe is born. Another important concept is Immanence. The Goddess is immanent in Her creation. She is not separate from Her creation, she is Her creation. … Her Son and Consort is the Mortal principle that is born, dies and is reborn in an ever-repeating cycle of birth, death and rebirth. The God also is of the Goddess. You could say that He is Her male aspect.”

One of the most common forms of the Neopagan Goddess is the Triple Goddess who is Maiden, Mother, and Crone (Wise Woman) in one and who is symbolized by the phases of the moon: waxing, full, and waning. (Some people add a fourth, dark phase for the new moon, which represents death.) Paul Reid-Bowen explains in his book, Goddess as Nature: Towards a Philosophical Thealogy, how the Neopagan Triple Goddess represents the Cycle of which her aspects are only parts:

“[T]he three aspects of the Goddess, Maiden-Mother-Crone, are theaologically understood not only to be pre- and post-patriarchal models of female identity, but also a dynamic whole: three aspects of a unity. And, while extensive thealogical energy has been invested into charting the character and meaning of each of these different aspects of the Triple Goddess, I am concerned with how the model functions as a dynamic whole. Notably, the model of the Triple Goddess is understood to have metaphysical significance because it is thealogically understood to illuminate broader patterns occurring within the whole construed as nature. The Triple Goddess emphasizes not only changes, cycles and transitions in terms of a female life-pattern, but also with respect to cosmology and ecology (lunar and seasonal cycles) and existential and metaphysical processes and states (birth/emergency, growth/generation, decay/degeneration and rebirth/regeneration).”

“[…] the model of the Goddess as Triple introduces themes relating to transitional change (both in women and nature) and also cyclical recurrence within a unified whole (understood as the Goddess as nature). The Goddess, according to this model, may be viewed as always changing, while at the same time manifest within recurrent patterns.”

“Thus, the triplicity of the Triple Goddess evokes a notion of diversity and difference within nature, while the unity of the Triple Goddess symbolizes the Sacred Whole, the unity of nature, expressed in the cycle of birth-growth-decay-regeneration.”

Zoe and bios: the unity of Life

In their book, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1993), Anne Baring and Jules Cashford illustrate the relationship of Goddess to the world using Karl Kerenyi’s distinction between the two Greek words for “life”: Zoe** and bios. According to Baring and Cashford, Zoe signifies the eternal and the infinite, while bios referrs to the finite and individual life, the latter being a manifestation of the former. Together they reveal the two facets of existence: eternal and transitory, latent and manifest, potential and actual, invisible and visible.

“[…] two different Greek words for life, zoe and bios, as the embodiment of two dimensions co-existing in life. Zoe is eternal and infinite life; bios is finite and individual life. Zoe is infinite ‘being’; bios is the living and dying manifestation of the eternal world in time.”

Baring and Cashford explain that bios represents the “manifesting” or epiphany (the “showing forth”) of the unmanifest Zoe, which both transcends and gives rise to bios. “Zoe is then both transcendent and immanent, and bios is the immanent form of zoe.”

Baring and Cashford use the image of the moon to explain the relationship between Zoe and bios:

“The moon was an image in the sky that was always changing yet was always the same. What endured was the cycle, whose totality could never be seen at any one moment. All that was visible was the constant interplay between light and dark in an ever-recurring sequence. […] The whole was invisible, an enduring and unchanging circle […] Symbolically, it was as if the visible ‘came from’ and ‘returned to’ the invisible – like being born and dying, and being born again.”

Cashford elaborates on this theme in her book The Moon: Myth and Image: “Zoe is an image of the cycle, and bios is an image of the individual phases: bios is born from zoe, dies back into zoe and is reborn from zoe, as the phases follow each other in the pattern of the cycle.”

Baring and Cashford also find this dynamic expressed in matrifocal myths of the Bronze Age about a “Great Mother” and her son-lover or her daughter:

“[…] the Goddess may be understood as the eternal cycle of the whole: the unity of life and death as a single process. The young goddess or god is her mortal form in time, which, as manifested life […] is subject to a cyclical process of birth, flowering, decay, death and rebirth.”

“In the goddess culture the conception of the relation between creator and creation was expressed in the image of the Mother as zoe, the eternal source, giving birth to the son as bios, the created life in time which lives and dies back into the source. The son was the part that emerged from the whole, through which the whole might come to know itself.”

“[…] the familiar drama of zoe and bios, in which the son-lover must accept death – as the image of incarnate being that falls back, like the seed, into the source – while the goddess, here the continuous principle of life, endures to bring forth new forms from the inexhaustible store.”

In this view, the hierosgamos, the sacred marriage, of the Mother Goddess with her lover takes on added meaning: it represents the mysterious connection between Zoe and bios. “The sacred marriage, in which the Mother Goddess as bride is united with her son as lover, reconnects symbolically the two ‘worlds’ of zoe and bios, and it is this union that regenerates the earth.” From this perspective, ancient pagan and contemporary Neopagan rituals are mythic dramas in which celebrants become reconciled to death and reaffirm their trust in the eternal Life (Zoe) which promises that, as darkness is always followed by the light, so death is followed by rebirth — albeit in a different form. The re-connection of Zoe (eternity) to bios (time) through myth and ritual permits a shift of consciousness from the particular life of the individual to the supra-individual life of the cosmos. Cashford explains:

“Then what, at the level of bios, appears as dismemberment, appears, at the level of zoe, as transformation. The challenge of the Mystery rituals was to shift the consciousness of the participants from bios to zoe, from looking at life in pieces to experiencing life as one complete whole.“

This is the mystery that the Presocractic philosopher Heraclitus sought to express in here:

athánatoi thnetoí

thnetoì athántatoi

zôntes tòn ekeínon thánaton

tòn dè ekeínon bíon tethneôtes

Mortals are immortals

and immortals are mortals,

living each other’s death

and dying the other’s life.

According to Baring and Cashford, the patriarchal solar god-culture severed the connection between Zoe and bios. Mythologically, the god refuses the hierosgamos with Goddess that is both consummation and death (see the Epic of Gilgamesh). The god’s origin in Goddess is forgotten and the god becomes Creator of a creation from which he is separate and which he orders from without. And with the changes in myth a new psychology and a new social order prevails. Nature and the sacred are split. The divine is “othered” and placed beyond the reach of humankind in a transcendent realm. Nature becomes an object over which the disembodied rational spirit exercises its dominion. Darkness (the unmanifest) is no longer seen as part of the cosmic cycle; it becomes mere absence, something negative, to be fought rather than embraced. Eternity is no longer the cycle of death and rebirth, but an unending life which can only be hoped for by the individual.

Through a panentheistic understanding of divinity, Neopaganism seeks to unite Zoe and bios again, to reconnect the divine and nature, the eternal cycle of Life with all of our particular lives and deaths. This union is not a static identification, as in pantheism, but a dynamic dance between the two, Zoe and bios, Goddess and god. As Harry Byngham, Chief of the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry, wrote so eloquently in 1923:

“Life springs out of the star-tissued womb of Nature as the virile son of the all-Mother. Life seeks reunion or religion with Nature, his mother, not however, by falling back into her arms and surrendering once more to some primordial slumber and dream, but by striving away from and with her, searching her, playing with her, dancing before her, wooing her, overcoming her, until she, who is eternally young as well as eternally old, responds like a maiden to his life and will and power, and, in the transfiguring ecstasy of union a new cosmic consciousness is conceived.”

There’s still some patriarchal “power-over” language in this quote, but I still like the imagery of striving, searching, playing, dancing, and wooing to express the mystery of the relationship between the immanent and the transcendent.

* Note: I use “Goddess” intentionally here without the definite article “the”, to emphasize the nature of Goddess as Be-ing, as opposed to a being. Indeed, it would be appropriate to understand “Goddess” not as a noun, but as a verb (i.e., Goddess-ing). I also defend the gendering of “Goddess” as (1) a necessary counterpoint to the traditional gendering of the transcendental God and (2) as an appropriate metaphor for the the source, ground, or womb of manifest existence.

** I capitalize Zoe to emphasize its supraordinate nature.