There are many stories throughout the Scriptures that teach us what happens when families fight. In fact, it could be argued that that is what a good majority of the book of Genesis is all about. From Cain and Abel to Jacob and Esau, all the way to Joseph and his older brothers, this book is chock full of family drama, vengeance, and out-and-out violence.

These stories are not included without reason, however. It’s not just drama for the sake of drama. There’s real anthropological and psychological meat for us to chew on.

In the story of Cain and Abel, for instance, we have a tale about two brothers who vie for God’s favor in the form of sacrificial offerings. Both brothers desire God’s blessing and favor, and when only one is perceived to have it, they get into a bitter rivalry that ends in spilt blood: Cain rises up and kills his brother Abel. This starts the downward spiral of seventyfold vengeance that culminates in a flood of epic proportions.

Fast forward a handful of generations to Jacob and Esau. On the one hand, Esau was loved by the boys’ father, Isaac, but on the other, their mother, Rebekah, loved Jacob. Family drama, am I right?! Mimetic jealousy of the highest order! On top of that, there was this whole business about the birthright and blessing from Isaac. Who was gonna get it? Well, tradition stated that it was to go to Esau, being that he was the eldest. But Jacob, being the heel-grasper that he was, used his deceptive nature to trick Isaac into giving it to him. This causes a near lifelong crisis that, on multiple occasions, almost ends in blood.

And finally, there is the story of Joseph and his brothers. And again, it all comes back to fighting over who is the “chosen one.” Who is gonna find favor? Who is “the man?” In this story, it was going to be Joseph, the youngest of the lot. At least, according to Joseph’s dreams. In them, it was implied that all of the brothers were going to serve the youngest. Joseph was going to be supreme among them. So, they plot to kill him. But instead, Joseph gets away, is sold into slavery, and then rises the Egyptian ranks until he becomes Pharaoh’s right-hand man. After some plot twists and a bit of deception by Joseph, it is revealed that Joseph indeed became “the man” among them, and there you have it, the dreams come true.

What can be gleaned, among other things, is that when we compete for God’s good graces, or our father’s blessing or birthright, we end up tangled up in mimetic rivalry that often ends in bloodshed. The same could be said about the two brothers in the Parable of the Prodigal Son.

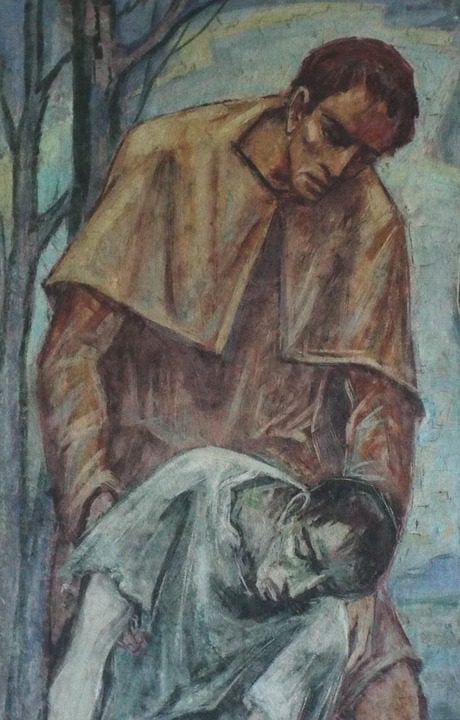

In this parable, after the younger brother squanders his entire inheritance, forcing him to become a swineherd, he comes crawling back to his father with his proverbial tail between his legs. His father, however, showing no favor to either son based on any merit or good-standing in the family, comes running down the lane to shower his son with love and, shortly thereafter, a celebratory meal. That is to say, the father showers his son with preemptive love, grace, and mercy.

This, as we’re all probably aware, pisses the eldest son off. He gets caught up in pure mimetic jealousy: “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!” (Luke 15:29–30) For the eldest, it was all about a quid pro quo: I did this so I deserve that; he didn’t do this so he deserves nothing! But for the father, who is to be a picture of God, there is no such exchange, no such mimetic set-up for the sons.

The father, rather than getting annoyed by his eldest’s jealousy, reminds him that, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found” (Luke 15:31–32). What we should notice here is that the father’s grace is free, and his love for his sons of equal breadth and depth. Unlike Isaac, who specifically loved Esau over Jacob, there is no favor shown one way or the other. One isn’t blessed over the other. Both are blessed equally. Everything that is the father’s is also the sons—both sons, regardless of their behavior.

Now, we certainly can see how this sort of unadulterated grace can cause scandal for many. We still tend to operate under systems of exchange, a tit for a tat and all that. We expect that our “good” behaviors will be rewarded while their “bad” behaviors will be punished. We expect the Deuteronomic God who blesses the righteous and punishes the wicked (see Deuteronomy 28). But God isn’t like that. As Jesus teaches us in Matthew 5:45, God sends rain on both the righteous and the unrighteous. God, like the father in the parable, gives all he has to both sons, regardless of their past deeds (or misdeeds).

Sadly, this is something that is often either missed or overlooked by many Christians. We tend to oversimplify things and only focus on the sons in the story. What we need to do, however, is focus a little bit of our attention on the father because it seems to paint a picture of God that is strikingly dissimilar to the gods we tend to concoct in our image. We approach things in an economic way and tend to create gods who act similar. We bless those in the right while punishing those in the wrong and we tend to think God acts like that. But not for Jesus. Not here in this parable. God is always giving all God has, even when we don’t think they deserve it.

Let us be less like the sons and more like the father.

Peace.

*If you want to support my work, please visit my Patreon site. You’ll get lots of goodies if you do!