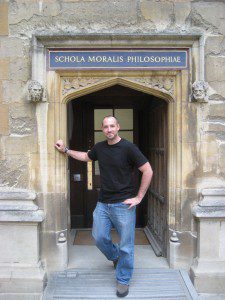

As I mentioned recently, I gave a talk last month at the Oxford Center for Buddhist Studies on the topic of Buddhist ethics, or more specifically, recent studies in Buddhist ethics. As Richard Gombrich pointed out in the Q and A, I didn’t mention karma at all in my talk. And I agree with him (see his 2009 book, “What the Buddha Thought” for details) that karma must play a central role in understanding traditional Buddhist ethics (what nontraditional Western Buddhists make of karma is a whole book in itself just waiting to be written).

In any case, my talk aimed to examine recent studies in Buddhist ethics, a somewhat peculiar area of research, and one that is still in need of much work. Despite a recent upsurge in recent scholarship in the field, especially in the last 20 years, there still remain many unresolved and indeed contentious issues. While audio from the talk is forthcoming, I will post bits and pieces here for comments and discussion:

~

Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies

February 27, 2012

Justin Whitaker

Concepts like knowledge, beauty, and meaning, as well as virtue and justice, all have a normative dimension, for they tell us what to think, what to like, what to say, what to do, and what to be. And it is the force of these normative claims – the right of these concepts to give laws to us – that we want to understand. And in ethics, the question can become urgent, for the day will come, for most of us, when what morality commands, obliges, or recommends is hard: that we share decisions with people whose intelligence or integrity don’t inspire our confidence; that we assume grave responsibilities to which we feel inadequate; that we sacrifice our lives, or voluntarily relinquish what makes them sweet. And then the question – why? – will press, and rightly so. (Christine Korsgaard “The Sources of Normativity” 1996, p.9)

The reason I begin tonight with a quote from a contemporary thinker is that as a philosopher and historian, I think it is important to begin with orientation, or context. Korsgaard’s statement is true, or compelling, for us in Western academia in the 21st century, and surely at least mostly true dating back to the age of enlightenment in the 18th century. It has been through these concepts that we have been trained to think and approach the world, and so naturally it has been through these concepts that academics have approached Buddhism in search of its sources of normativity.

But very quickly we discover that Buddhist normative concepts are all just a little different from what we had hoped to find. Buddhists, and I speak primarily from the perspective of early Buddhism as represented in the Pāli canon, seem more interested in ignorance than knowledge, more likely to discuss suffering and renunciation than beauty…

And so the philosopher seeking normativity quickly becomes the philologist, or at least amateur philologist, seeking to understand words. As the meanings and context of the words emerge, we begin to get a glimpse of the scriptural norms for Buddhists who claim to adhere to them today. And through these textual readings we are able to begin to understand Buddhist ethics.

In terms of this foundation of philology, people working in Buddhist ethics today, such as myself, have had the great fortune of standing on the shoulders of giants. The early 20th century saw great advances in translating Buddhist texts and the formation of the still essential “Pāli-English Dictionary” by T.W. Rhys Davids and William Stede (1921-5).

A second foundation for the study of Buddhist ethics has been anthropology. It has been through anthropology, largely in the last 50 years, that we have been able to see how Buddhists understand moral concepts themselves. Work in the field by scholars such as Winston King (1964), Stanley Tambiah (1970), Melford Spiro (1970), and Richard Gombrich (1971) helped shape useful lenses, or interpretive categories, through which others could then look back and better understand the words and deeds of past Buddhists.

~

In a few future posts I will discuss the ’emergence’ of Buddhist ethics in the 1970s, its flourishing in the 1990s, and the issues still fueling debate within the discipline today.