Buddhism has always held that all phenomena are transitory, including both the teaching of Buddhism as we know it and the world itself. While the Dharma -speaking of the Truth he came to understand – is universal, eternal, and uninfluenced by particular human circumstances, the sāsana, or lineage of teachings handed down for the last 2400+ years, will come to an end.

Likewise, Buddhism inherited the cosmology of Proto-Hinduism (Brahmanism), which held that humans today are living in an age of decline. Part of this sense of decline is the belief in growing immorality and warfare. Conversely, the level of emphasis this belief has taken on in Buddhist cultures often reflects a world around them engulfed in war or simply persecution. The belief exists in all schools of Buddhism, though it took on heightened urgency in China. There the idea that the decline would have a phase of “final dharma” (mofa), starting in 552 C.E. was established, and in Japan the same belief, termed mappō was transmitted with the updated start-date of 1052 C.E. *

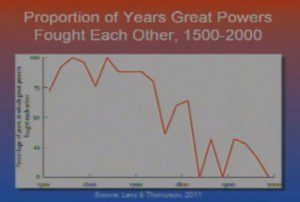

However, as Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker writes in his new book “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined“, this hasn’t been the case. In fact, things are getting better. His work is largely a tour de force of collected statistics. Take the middle ages for instance. While good records weren’t kept everywhere, from what we do have, it is clear that a lot of people were murdered. Just looking at homicides, Pinker determined that you were 35 times more likely to be murdered in the middle ages than today. 35 times!

Stats for warfare follow as similar trajectory. While warfare, homicide, and other forms of violence obviously do continue, the fact is that, proportional to population, they are declining. It is that “proportional” part that might cause difficulty for many people. Millions of people died violently in the 20th century, more than in any before: doesn’t that make it the most violent century ever? In just raw numbers, yes. But in terms of any individual’s likelihood of dying violently, no.

As Colbert quips in the clip below: if you kill 1 million people in nation that has 2 million, that’s pretty bad, but if you kill 1 million people in a nation that has 40 million, that’s progress?

Yes.

Here’s an excellent recent discussion of the idea by Pinker and Robert D. Kaplan via the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs:

Video streaming by Ustream http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/25752052

Kaplan, author of The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate, points to East Asia as a model of modernization, but notes that part of the result is a massive arms race and increasing nationalism – note the recent standoffs between Japanese and Chinese ships regarding two tiny islands.

While there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of continued antagonisms around the world, this doesn’t refute the statistics, which – as a bit of a math nerd – I feel are both incredibly important and widely overlooked by most people. One unfortunate, but common, side effect of citing anecdotes is the tit-for-tat kind of arguments that Kaplan has at one point with a gentleman who lived in Singapore in the 1960s and 70s. The power, and for me, beauty of these wide-scale statistical views is the fact that you can swallow up anecdotes: sure, there is war, but look at how much less there is now vs the past.

But people like stories, now as much as before. The interesting thing about stories is that they can compel people to do things in a way that statistics never could. The Buddhist stories of decline were probably meant as moral exhortations, saying: “look at yourselves. The world could be so much better and, in fact, it once was. Let me tell you about it…” When we look at these stories we cannot lose sight of this moral lesson. Today people just read the stories as if they were fanciful fairy-tales conceived in a pre-scientific age. As if people 2500 years ago (and this goes for Biblical stories as well) couldn’t count up to 100, so they believed some people could live to 200, 1000, or older. Of course this is often a reaction to meeting people (we tend to call them fundamentalists in the West and traditionalists in the East) who do actually believe the stories on face value. What we need is a middle ground. Something solid. Statistics. (And graphs.)

The Colbert Report

Get More: Colbert Report Full Episodes,Political Humor & Satire Blog,Video Archive

More about Pinker: http://pinker.wjh.harvard.edu/about/