One year with no TV, no cell phones, no email.

“You’re kidding, right??!!” That was the response from one retreatant’s daughter, at least.

But no, no kidding.

March 31st marked the first day of a one-year retreat for around a dozen members of Kagyu Changchub Chuling “KCC”, a center founded by the renowned Tibetan teacher Kalu Rinpoche in Portland in 1976. Along with the retreat leader, Lama Michael Conklin, and a small support staff are a doctor, a hip-hop artist, an agriculture specialist returning from Afghanistan, a retired teacher, a university professor, and eight other men and women. Together they will venture into a secluded retreat center near the small town of Goldendale, Washington.

Just before they went into retreat I was invited to submit a few questions about the retreat to both the retreatants and Lama Michael.

As I awaited word back and consciously cut back on my social media exposure as part of my own mini-retreat or “unplugged” April, I happened upon a well-written reflection from Daniel Warner, whose friend recently walked away from his successful fashion design life to ordain as a Buddhist monk:

I look at the things I have amassed over the years and surrounded myself with, and not just the material things (of which there are many) but also the relationships and friendships I’ve nurtured or walked away from. I look to the rituals and ‘quirks’ I have that allow me to leave the house every morning and prepare me emotionally and physically every day, and I wonder if I could ever truly give them up? I try very hard to live a simple, uncomplicated life but when I think about the minor details that make my day run smoothly, things like a perfectly timed tube arrival and then actually getting a seat, or a deadline met with time to spare, or even down to just getting my favourite shower stall at the gym and I wonder, could I ever give up the inconsequential for a months worth of meditating and quiet reflection? Are any of us willing to let go of the things we can control to gain a little more insight into the things that make us ‘tick’?

As a regular (though very lazy) meditator, I look upon both stories with a twinge of jealousy (and plenty of mudita, or sympathetic joy!). But I also share that same sense of uncertainty: could I do that? Would I? What would people think?

My questions to the retreatants reflected these concerns.

JW: Can you talk a little bit about your emotions as you count down to the retreat?

Going on the one-year retreat didn’t seem real for quite a while. At times I even hoped my teacher would not accept me on the retreat. A few months ago I woke up in the night with panic attacks. However, the great support of the KCC community and my family has been inspiring. Even tonight, the evening before I leave home for a year, I have some nervousness, but also anticipation. We had a year to prepare for this and now it is here. My husband and son have always been supportive. They are very adventurous. However, my daughter and mother expressed some concern. We are very close and talk a lot. We will miss that intimacy. – Kay Hartsock

JW: Do you have a greatest hope and/or fear about the next 365 days that you would like to share?

My greatest hope is that I will reach some stability in my meditation practice — a quiet mind that can be open to seeing how things really are. My fears include losing faith in the practice, getting homesick and lonely for my family, getting sick. – Kay Hartsock

First, I need to say that I am so happy and amazed that conditions have come together for me to engage in this extended retreat! It is a rare opportunity for growth-hopefully toward more wisdom, compassion and kindness in my own heart and mind-and then my hope is to act with that always. What I have heard about going into retreat is to have no expectations, just to be happy and grateful to have the chance to improve the mind and heart. This has been very good advice and has helped me calm down when I start getting nervous or upset about the small issues that appear when getting ready. I think all of us going on this truly hope to increase the peace in our minds, our families, with our friends, our work mates and then extending out in ripples to all.

– Kathleen Herron, Karma Zopa

JW: This tradition of long retreat is still extremely rare in the US. How have people you have talked with about it reacted? Are friends, family, coworkers and broader community bewildered, worried, supportive, etc?

When a friend of mine went on a one-year retreat about a decade ago, I couldn’t understand why she would do such a thing, but I didn’t say anything. I am assuming that people who don’t understand or think it’s crazy keep those opinions to themselves. Most people are kind that way. However, I am sure some are bewildered and definitely some are worried. The most vocal people are very supportive.

My daughter, Genevieve, just called and we talked for over an hour (as usual). I wanted to write what she said since it relates to the interview questions. Genevieve is 25 and we have always been very close. “Mom,” she said, “I will miss you so much, but this is your next step. You’ve had an inner spiritual practice for over 40 years. As long as I’ve known you, you’ve been doing this. When I tell the people I work with and my friends what you are doing, they are amazed and think you are very brave. It’s something very few people get to do — and you’re getting to do it with a group of wonderful people. I’m happy for you. It’s going to be wonderful. I admire you so much for doing this.”

Genevieve was not greatly enthusiastic about the retreat when I first told her. When she found out there would be no email (to quote her, “You’re kidding, right??!!”), she was even less enthusiastic. However, over the months of talking about it, she began to understand. She came to the KCC Retreat Celebration and left feeling much more positive about the coming year. “They are really wonderful people,” she said about the KCC sangha. “It seems so many people are inspired by this retreat. I know Dad is inspired by it and you’ve known him even longer than you’ve known me — or maybe not. Maybe we’ve known each other forever.”

– Kay Hartsock

Responding to the same question, Julie Hurlocker responded:

There has been some of all those responses, but with much more emphasis on “support”– especially from the ‘least likely’ people. (ie members of my family who are anti-religion and not particularly spiritually inclined)

There appears to be a great yearning out there for experiencing something beyond this self-centered drama: for seeking a greater happiness than merely ‘getting what I want’. There is a recognition of something basically ‘unsatisfactory’ about a lot of what we occupy ourselves with and, therefore, I have experienced a ‘cheering’ from the crowd to continue the inward journey. Even though many of the specific practices of our tradition are not familiar to them, for many of my friends and family the common aspiration to be useful, to be of service; to cause less harm and to find therein a deeper peace seems an almost universal wish.

Similarly, when thinking of a big retreat, it is the people in charge that can make it – or break it – for everyone involved. With that in mind I wanted to ask some more specific questions of Lama Michael, especially in light of some recent problems – which he kindly obliged.

JW: Beyond your bio, can you tell us about your own journey into and through Buddhism? What were some of the key turning points in your path, insights, challenges, etc?

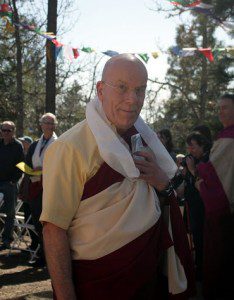

Of course we could talk for 3 days about journeys into things, or longer! I will summarize it. I had no intention of becoming Buddhist – no interest. It was an accidental encounter with Buddhism back in 1974 that started me on this path. I went with a friend to see a teaching given by Kagyu master Kalu Rinpoche. Even an hour before seeing that talk, I probably would have said that it would be highly improbable that I’d have interest in Buddhism or any other religious tradition. It was therefore kind of surprising how quickly it became clear that I was willing to set forth on this path. It happened in almost a matter of minutes. We have in Buddhism “the truth of interdependence.” If I would have met him 2 yrs earlier, nothing would have gelled. But at this time, there was a lot of suffering in my life, and Kalu Rinpoche, by his mere presence, showed the possibility of change.

It was not necessarily a pleasant journey for the first dozen years because I still was not interested on many levels. But I couldn’t deny the connection with Kalu Rinpoche. I knew he was the real thing – not one of the people I’d judged as a hypocrite or fundamentalist before. Everyone comes to Buddhism through different doors. I was part of the 60s movement when people were cynical and questioning the traditions that they had grown up in. I was in San Francisco, which Chogyam Trungpa called “The Great Spiritual SuperMarket.” There was suddenly lots of new age religion, variations of Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, etc. It wasn’t necessarily healthy from a spiritual standpoint, but it was exhilarating. That was the milieu.

When I met Kalu Rinpoche, it was a little like riding toward Niagara Falls: You don’t see the falls until you’ve just gone over it. You HAD a choice at some point along the way, but, in the moment of going over the falls, you no longer do. In a way, I loved that there was no choice, but it did reorient my life completely so I felt like I was starting again.

JW: You have been at this for going on 40 years now. Did you have any visions or ideas back in the 1970s about what Buddha-Dharma might look like in the US in the 21st century? How has reality come to meet or fail to meet those ideas?

I had no idea. I didn’t really think about it. Of course, I did witness the Dharma growing. In the early days, there were only two books on Buddhism in the Shambhala bookstore, which has grown into the major publisher we now know. By the time I went on long retreat, there were about 200 books. So I witnessed Buddhism growing very fast, particularly in San Francisco and Berkeley. Most people came and went. They’d try it and quit, or they’d try something else and come back. Not many people had a solid connection at that time.

Trungpa Rinpoche visited KDK in San Francisco and said that Buddhism does not grow because of institutions and dharma centers. He said it only grows through practice. So one can be part of the growth, or they can be part of the end. I wanted to help, though at that point I still wasn’t totally interested in all of the practices of Buddhism. That took a while to develop.

JW: What are the prerequisites for a 1-year retreat in your tradition?

When we started talking about one and 3 yr retreats, I asked myself whether I was qualified to choose who goes into such a retreat. I realized quickly that I was not! I felt totally incompetent. It was still a long ways away at that point, so I started talking to some psychologists. Some told me that they’d be able to tell who should obviously not go into a long retreat – such as someone with paranoid schizophrenia – and that I’d be able to see that for myself. But no one felt confident that they’d know who would actually succeed in such an environment. I talked to a priest in charge of screening applicants in the Archdiocese. He admitted the seminary is nothing like a long retreat, and asked, “have you tried talking to NASA?” It’s a rare person who can go on a mission with NASA! Of course, as this priest pointed out, NASA has thousands of applicants and it’s easier to find a few stalwart people among them. We don’t have that option. We will never have that many applicants!

I have come to some conclusions. One needs to have an experiential – not just conceptual – understanding of the causes of confusion in the world—an understanding of how our emotions and intellect lead us astray and cause suffering in the world. Retreatants have to be familiar with the disease itself. And it is helpful to see it as a disease, not a character defect. It’s something that we have – that we’re bewildered by. This means, by extension that retreatants have done a fair amount of practice. Maybe 1000 hours? Of course someone might be qualified with a 100 hours, or others will have insights into our suffering more immediately. But 1000 hours is not a bad marker. On a 1 yr retreat, they’ll do about 4000 hours of practice.

For this retreat, it’s good if they have the Milarepa empowerment for a ritual we will do in the retreat, but they don’t need to have finished or done a lot of Ngondro (foundational) practice. Age is not a deciding factor. Ordinary psychological health is important. There’s no requirement to be free of suffering. The world contains a high level of neurosis. As Alan Wallace has said, there is a very low bar of sanity in this world. We should at least meet the low bar of normal psychological health in the world before starting the retreat. Chogyam Trungpa would send people to psychologists sometimes to deal with ordinary psychological troubles – even if those issues may have just been things like being too controlling or blaming others too much. He’d say, see a therapist, and come back and then maybe you can then engage in certain practices or enter retreat.

Not much of this is objective, measurable criteria, which is why I felt incompetent in the beginning.

JW: Many of us followed the news out of Bowie, Arizona last year quite closely, where a Tibetan Buddhist retreat fell into troubles and the retreat leader and her boyfriend were asked to leave (link). The two wound up staying in a nearby cave until, tragically, the boyfriend passed away from dehydration and exhaustion. While tragedies like that are extremely rare, I understand you must have some ‘fail-safes’ in place to ensure the safety and health of the retreatants. Could you talk a bit about that?

This is a great question and this situation opens up a whole area that is and should be of deep interest to everybody. A couple things need to be said first: 1) I feel certain I don’t have all the information about what happened there. There are some things that I heard went on, which I don’t like, but I am not totally comfortable in a judgmental mode. 2) There has not been any major religious tradition free of these things. If I were to be a Christian, I would be horrified by atrocities that happen related to other Christians. Similarly, I feel that with what happened in Arizona. I feel sad about what happened to the people and about its impact on the tradition. We are at a fragile time and long retreats don’t have public support. There is a lack of understanding about what retreat is about. But, in this world of confusion, there will always be terrible things that happen. I could go away for 2 weeks after having talked to each person in the retreat, and come back and find that some terrible tragedy has occurred. And some would say that this means that long retreats are evil, and we’d be left with no way of knowing or testing whether this tragedy would have occurred with or without the retreat in place.

What I’ve read is that, in this situation, there were a lot of things that contributed to an unhealthy level of isolation. Comments by Michael Roach appeared to set his approach apart from the rest of the Buddhist community. The retreat center was quite remote and the retreat cabins themselves were separate by significant distances – one couldn’t see any other cabin from one’s own cabin. I’ve read that people would spend months there without coming out. That’s pretty tough. We have a lot of evidence that would indicate that there might be serious psychological problems resulting from such isolation.

So it sounds like that was a very high-risk situation. In Tibet, there weren’t very many people who lived alone in caves. It was unusual. We know about the great survivors – the Milarepas – but others probably did not survive. It’s a romantic idea. And very high-risk. That is why we have 2 group practices each day – morning and evening. If you are having a serious psychological problem, it will be difficult to hide it. Retreatants will have access to several different teachers. We also have avenues for people to be in contact with people outside of the retreat.

Experimenting is part of a spiritual path, but the leadership must be very careful to keep its nose clean. I have to assume that Michael Roach likely wanted to help people, but he had said and done some things that estranged him from individuals like the Dalai Lama, and thus from much other leadership long ago. When criticisms and concerns were raised, it seems like they were ignored. It’s better to change the tire when you first hear it flopping on the pavement outside of your window, rather than driving another 500 miles. So now, though he may want to help others, it will be hard in this life to get his “spiritual currency” back. I have no beef with Michael Roach, as I’ve never met him. I do hope something good comes of that situation.

The truth of interdependence means we cannot see all the variables functioning and therefore cannot always avoid difficulty. But of course we make efforts to prevent problems at our center. Rather than placing the teacher at the top of the organization, our structure places the Board of Directors on a par with the Resident Lama. Also, the Board and the sangha have the power to remove the Resident Lama. And we have a grievance procedure. As Resident Lama, I often try to make suggestions to the organization in the spirit of: “just consider this perspective.” I specifically want to avoid being taken to mean: “we have to do this.” We have to empower people to stand up and say what’s on their mind, and have balanced, talented and qualified people to make decisions. There is a problem when someone has too much authority; even the Dalai Lama does not take absolute authority.

JW: Along similar lines, there have been a number of sex scandals and allegations in recent months regarding Buddhist teachers and their students. Again this is relatively rare given the numbers of practicing Buddhists in the US, but hopefully we can learn as much from groups like yours that have not had these problems, as we can from those who have. Do you have a code of conduct or set procedures for conflicts arising from sexuality in your center or broader lineage?

We don’t have as much in place as we would like to have or as we would have if our organization had more resources. We follow the 5 basic precepts, which includes no sexual misconduct. Of course, culturally, there are different definitions of such a thing. At one point in the 70s, Kalu Rinpoche had expressed that, if you were in an intimate relationship with someone currently, it should be for life. In San Francisco at that time, this may have been a culturally unrealistic rule.

In any case I feel that one of the best antidotes to abuse of privilege is education. As an organization, we need to talk about the dynamics that are at work. How, within the organization, the leaders wind up with more institutional currency/power. People need to know that they can say what they need to say if they disagree with the leadership.

Ultimately, having the conversation and continuing to have it throughout the organization is the best way to create health. We need more on this score, and we need to further develop our grievance procedures and make sure they are public and that everyone knows

about them.

JW: Surely India or Nepal could provide amazing, well-established facilities for such a retreat. Why do this in America, in rural Washington State, no less?

We wanted a rural place where we were allowed to build. We looked – I mean really looked – for about a year, and in all our searching, we found 2 parcels that would have worked before deciding on the land outside of Goldendale. There are many reasons why it’s difficult for individuals to do it in India. Cultural and language differences are of course a challenge. The food is not our food and the medical care situation is different. There, you need to be fluent in Tibetan – not just be able to order off a menu and very few practitioners have learned Tibetan at this level.

But for us it is not just a matter of the difficulties of training in Asia. As an organization, KCC chose to make this effort because retreats of this nature have been essential to keeping the dharma alive over the generations. If the Dharma is going to take root in this country it is essential for retreats like this to become part of the natural fabric of Dharma life, not just an exotic thing that happens far away. The members of our community are stewards of the land where the retreat is, we built the facilities for this retreat and now community members are going onto retreat. So the retreat that is just starting really feels like it is our retreat, it is very much a part of the life of our community.

JW: Anything else?

That is it. Thank you for this conversation!

And thank you, Lama Michael, to the retreatants, Kay, Kathleen, and Julie, for your time and thoughtful responses, and to Bill Schneider for all of the help in connecting us.

My best wishes for a fruitful year to all, both in retreat and out.