In which I meander through four philosophers: Weil, Marx, Kant, and Scruton and, somewhat strangely, take up a conservative position regarding the ‘revolution’ in Egypt…

The word ‘revolution’ is a word for which you kill, for which you die, for which you send the labouring masses to their death, but which does not possess any content.

– Simone Weil, Oppression and Liberty

Born and raised as a Jew in France in the early 1900s, Weil was drawn to philosophy, mysticism, and political activism in a time when all, in some way or another, were desperately needed. She studied religions of the east and west, and philosophy from the Greeks to Kant and Marx. She became fascinated with and sympathetic to the Cathars, a branch of Christians tracing themselves to early Christianity. They had survived for a thousand years, settled in southern France between modern-day Toulouse and Narbonne. Then in 1208, a crusade was launched against them by the Roman Catholic Church which over the next hundred or so years “killed thousands with merciless cruelty,” writes a Weil biographer, Stephen Plant.

Christian ‘holy wars’ would then ravage Europe, parts of N. Africa, and the Middle East for centuries.

Weil, who was fond of Marx, nevertheless found his model of human progress via economic revolution to be overly simplistic and, as the early 20th century played out, patently false (at least when driven by fallible humans – as history always will be). Contemporary Marxists quibble over the details and continue to ‘fine tune’ his system, but the heart of Weil’s argument, which draws from Kant, is that ‘revolutionaries’ often overthrow one despot only to run into the arms of another. For a revolution to work, it needs to start at a base and consist of people reaching out to others.

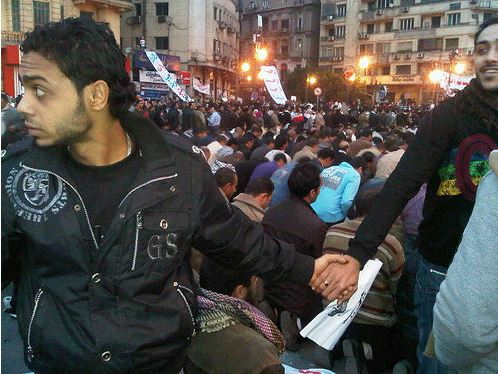

Kant wrote in “What is Enlightenment” in 1784 that revolution has the potential to put ‘an end to autocratic despotism and rapacious or power-seeking oppression’ and indeed it does have this power as we saw in Egypt in 2011. Then the ‘enemy’ was simply one man, one way of government that no longer served the people. Some, of course, benefited from Mubarak’s rule and thus sought to keep him in power, but the vast majority didn’t and thus came together in opposition:

When the military deposed Mubarak, we all had good reason to be optimistic. They vowed a democratic process once security returned and they fulfilled their promise. Eventually the Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate, Mohammed Morsi, became president. He vowed to reach out across divisions within the society in mid 2012. But soon things changed.

On 22 November 2012, Morsi issued a declaration purporting to protect the work of the Constituent Assembly drafting the new constitution from judicial interference. In effect, this declaration immunises his actions from any legal challenge. The decree states that it only applies until a new constitution is ratified. The declaration also requires a retrial of those accused in the Mubarak-era killings of protesters, who had been acquitted, and extends the mandate of the Constituent Assembly by two months. Additionally, the declaration authorizes Morsi to take any measures necessary to protect the revolution. Liberal and secular groups walked out of the constitutional Constituent Assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamic practices, while members of the Muslim Brotherhood supported Morsi.

The move was criticized by Mohamed El Baradei who said Morsi had “usurped all state powers and appointed himself Egypt’s new pharaoh.”

– Via wikipedia; the details of Morsi’s decrees can be found at the Egypt Independent.

This is the other way a revolution might go. Kant saw this in the French Revolution, which he was very hesitant to support (recall The Reign of Terror). Kant also wrote (in the same document mentioned above) that revolution presented a potential source for new prejudices which ‘like the ones they replaced, will serve as a leash to control the great unthinking mass.’

The Reign of Terror made Kant and many others in Europe hesitant to advocate any kind of revolution against a sovereign (monarch). Then, as now, the sovereign would be the head of the military. In the Metaphysics of Morals (1797), one of his last works, Kant stated unequivocally that if constitutional change should be necessary, it should be done “only through reform by the sovereign itself, and not by the people, and therefore not by revolution.”

By this we might infer that Kant would have supported the military removal of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 and would again support the military now in removing another illegitimate political leader who tried to alter the constitution both above the judicial law of his country and against the will of fellow politicians.

The military is the sovereign and all reform must take place under its approval. Even the eventual move to divest the sovereign’s sovereignty to the people must be a conscious act of the sovereign.

This is an important move, so I’ll repeat it: the sovereign (military or monarchical) must eventually consciously divest its sovereignty to the people.

In England, where I live now, this was largely done between the very bloody 17th and the 19th centuries, and today the monarchy, while technically still in charge of everything, plays a merely ceremonial role. Roger Scruton writes of the English experience:

In the 17th Century our country was torn apart by civil war, and at the heart of that civil war was religion – the Puritan desire to impose godly rule on the people of Great Britain regardless of whether they wanted it, and the leaning of the Stuart Kings towards a Roman Catholic faith that had become deeply antipathetic to the majority and a vehicle for unwanted foreign interference. In a civil war both sides behave badly, precisely because the spirit of compromise had fled from the scene. The solution is not to impose a new set of decrees from on high, but to make room for opposition, and the politics of compromise. This was recognised at the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when Parliament was re-established as the supreme legislative institution, and the rights of the people against the sovereign power were reaffirmed the following year in a Bill of Rights.

In Egypt, the sovereign (the military) stepped back in 2011 and established a civilian government that started out okay, but then turned against various minorities (secularists, Christians, etc.) and thus defeated its very purpose as a government of the people. As Scruton stated:

Look at the pronouncements of the recently elected and recently deposed President Morsi of Egypt, however, and you will find little or nothing to suggest that he is aware that there are Egyptians who disagree with him and whose consent must be constantly solicited. It is impossible to discern from his speeches that there is a substantial minority of Egyptian citizens who are Christians, others who are atheists, others who, while following the Muslim way of life, would rather it did not make a show of itself as the state religion.

His view of elections is that they grant an absolute right to impose the ruling party’s agenda, and that opponents have lost all right to an agenda of their own. And the response of the army is to say, not so…

In no “democratic” nation could Morsi have gone so far as he did. Suspending judicial oversight? Hastily drafting a new constitution with the support of only one party? No. This is not how democracy works. This is autocracy and it is a wonder that the army waited as long as they did.

What now?

If you agree with the military’s actions, then the next step is to a) join Coptic Christians and others who seek to restore stability, just as was needed after the overthrow of Mubarak, and 2) to initiate steps toward a new democratic election.

Unfortunately, the church was later destroyed by arsonists (see here). Reading THIS IS WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE JUST BEFORE THE MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD JUMPS YOU, you get to see some of the chaos which is the current state of Egyptian life on the streets. We should note that 1) the majority of Muslim Brotherhood (MB) supporters are peaceful, but also that 2) the large crowds allow and sometimes support thug violence and the most extreme elements… So it makes no sense to blame the MB as a whole for recent violence, but we also cannot ignore the connection.

And for the leaders of the MB to call for “days of rage” (or “anger” – I don’t know the full gloss on the Arabic term being used), is not helping – at all.

Whether it is just vandals and thugs “hijacking” MB protests or not doesn’t make much difference to those attacked or to outside observers. Once violence breaks out, it is a violent protest and security forces have an interest in stopping it before it spirals out of control.

This is the lesson from Kant, from Marx if “correctly” read, and from Weil. Taking power as a political party doesn’t mean you can take absolute power over the people (i.e. become the next despot). Democracy is messy, but it must be pursued because anarchy is much messier and absolutism is a darkness into which no sane person would venture.

In Egypt, democracy must start with the military now (who willing seceded before and will again, we hope) and must rely on an eventual government of the people with a leader who doesn’t willingly exclude all others in a race for his own bid to become ‘pharaoh’–or divine king for Christians or chakravartin for Buddhists. Politicians need to stay out of overt (and often divisive and hateful) religious activities and this goes no less for the US or UK or Burma than it does for Egypt. We can only guess how much G.W. Bush’s mention of the word “crusade” destroyed hope of uniting people against radicals in 2011 and fueled the recruitment efforts of violent anti-American groups. Imagine our reaction if U Wirathu or his likes were to enter politics and be elected to the highest office in Burma.

Egyptians, we hope, are not discouraged by the democratic process, but rather will seek to learn from the failings of one government in their preparations to elect the next.

Of course drawing analogies from distant places and times is open to counter-example and arguments of dis-analogy. Perhaps Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood is more like the Christian Democratic Union of post-war Germany than the Puritans and Roman Catholic Church of the 17th century or the 20th century Soviets discussed by Scruton.