A make-up video as a topic for Buddhist reflection? That probably won’t be everyone’s cup of tea, but I’d say give it a watch, or skip right to the reading below it.

The description of the video, published last month, reads “The power of make up is incredible, but the power of you is cray cray.” And since I came across this via the wonderful Full Contact Enlightenment page on facebook, I gave it a watch.

While much of it is the sort of feel-good, youthful optimism we either love or hate, the end message especially caught my attention. As she, Anna Akana, says toward the end:

The message of this video is pretty obvious. Take care of this [motioning to her face], but make sure you’re taking care of everything behind it as well. One thing that I really like to do is, I’ll look in the mirror, and I’ll imagine that I’m rapidly aging, until I’m just a skull. Like I’ll have the flesh falling off and wrinkles and maggots going through the eye hole and everything. And I don’t know if that’s exactly mentally healthy, but it’s a nice reminder about the impermanent nature of our flesh.

What started as an “everyday make-up routine” ends with a surprisingly ancient practice, described here by Bhante Gunaratana:

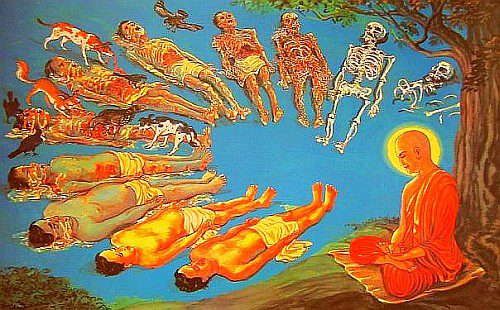

The ten kinds of foulness are ten stages in the decomposition of a corpse: the bloated, the livid, the festering, the cut-up, the gnawed, the scattered, the hacked and scattered, the bleeding, the worm-infested and a skeleton. The primary purpose of these meditations is to reduce sensual lust by gaining a clear perception of the repulsiveness of the body.

This is just one of the forty meditation subjects prescribed in Theravadin Buddhism and none of them should be practiced without the guidance of a qualified teacher. These particular meditations are meant to “attenuate sensual desire, [and] are suitable for those of greedy temperament” according to Gunaratana.

Immediately after giving this breakdown Buddhaghosa adds a proviso to prevent misunderstanding. He states that this division by way of temperament is made on the basis of direct opposition and complete suitability, but actually there is no wholesome form of meditation that does not suppress the defilements and strengthen the virtuous mental factors. Thus an individual meditator may be advised to meditate on foulness to abandon lust, on loving-kindness to abandon hatred, on breathing to cut off discursive thought, and on impermanence to eliminate the conceit “I am” (A.iv,358).

Douglas Burns also writes, drawing from the same tradition:

The last of the body meditations are the nine cemetery meditations. Numbers 1, 2, 5, and 9 respectively are quoted here. The remaining five are similar and deal with intermediate stages of decomposition:

And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body dead, one, two or three days, swollen, blue and festering, thrown in the charnel ground, he then applies this perception to his own body thus: “Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.”And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground, being eaten by crows, hawks, vultures, dogs, jackals or by different kinds of worms, he then applies this perception to his own body thus: “Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.”

And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground and reduced to a skeleton without flesh and blood, held together by the tendons…

And further, monks, as if a monk sees a body thrown in the charnel ground and reduced to bones, gone rotten and become dust, he then applies this perception to his own body thus: “Verily, also my own body is of the same nature; such it will become and will not escape it.”

Similar meditations on the digestion and decomposition of food are listed in other sections of the Pali scriptures for the purpose of freeing the practitioner from undue cravings for food:

When a monk devotes himself to this perception of repulsiveness in nutriment, his mind retreats, retracts and recoils from craving for flavors. He nourishes himself with nutriment without vanity…[27]

While these meditations are intended to eliminate passion and craving they carry the risk of making one morbid and depressed. Therefore the Buddha recommended:

If in the contemplation of the body, bodily agitation, or mental lassitude or distraction should arise in the meditator, then he should turn his mind to a gladdening subject. Having done so, joy will arise in him.[28]

or her!