Earlier this month we set out a home-work assignment of sorts for those interested in exploring more of the rich diversity in contemporary American Buddhism. That assignment was to get Diana Eck’s 2001 book A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Has Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation and read/discuss the chapter on Buddhism.

Earlier this month we set out a home-work assignment of sorts for those interested in exploring more of the rich diversity in contemporary American Buddhism. That assignment was to get Diana Eck’s 2001 book A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Has Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation and read/discuss the chapter on Buddhism.

Eck begins this great book by drawing attention to a shift that has occurred in her lifetime as a baby-boomer:

The religious landscape of America has changed radically in the past thirty years, but most of us have not yet begun to see the dimensions and scope of that change, so gradual has it been and yet so colossal. It began with the “new immigration,” spurred by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, as people from all over the world came to America and have become citizens. (p.1)

That period marks a key point in the lives and religious imaginations of many Americans. However, as Mushim Patricia Ikeda pointed out her recent “Crossing the Great Divides in US Buddhism” that period doesn’t mark a beginning to the story of Buddhism in America, which goes back well over a hundred years.

Reading on, Eck describes her work, beginning in the 199os, of mapping religions in America with the Harvard Pluralism Project. Coming to Buddhism, she writes:

We are astonished to learn that Los Angeles is the most complex Buddhist city in the world, with a Buddhist population spanning the whole range of the Asian Buddhist world from Sri Lanka to Korea, along with a multitude of native-born American Buddhists. Nationwide, this whole spectrum of Buddhists may number about four million. (p.3)

Here, Eck seems to imply the “Two Buddhisms” (Asian Buddhists… along with… native-born American Buddhists) model. While it’s a somewhat unfortunate wording – countless Asian Buddhists are also native-born American Buddhists – the notion of categorizing Buddhism in America in this way dates back several decades. As one of the early proponents of the typology, Charles Prebish, notes, describing “Two Buddhisms” along with Jan Nattier and Martin Baumann’s different “Three Buddhisms”:

Each of these typologies and labels had supporters and detractors, and each, to some extent, worked well as a description for a particular time and circumstance. Typologies, however, are never set in stone. Today, Buddhism in America is incredibly diverse and no longer seems to fit into the neat typologies of previous decades.

(2006, Introduction to a BuddhaDharma Forum on Diversity and Divisions in American Buddhism – see this article for an excellent discussion with Socho Koshin Ogui, Rev. Ron Kobata, Wakoh Shannon Hickey, and Duncan Ryuken Williams)

Yet, as Mushim noted in her recent post, if you ask white converts to describe of three to five “typical American Buddhists” you’ll likely get a vastly different response than if you had asked the same question of folks in a Buddhist group founded by Asian Buddhist immigrants. As she puts it, “between these groups [there] is what seems to me like an almost impenetrable wall, often, or an abyss in which phone and Internet signals mysteriously disappear.”

The rest of Mushim’s article is a wonderful prescription for surmounting, or at least chipping away at, that impenetrable wall.

And the 80-page chapter on Buddhism in America in Diana Eck’s book is an excellent starting point for doing just that. Her chapter begins in Los Angeles, which she says “is unquestionably the most complex Buddhist city in the world” (p.148). Here we find Hsi Lai Temple, east of town in the suburb of Hacienda Heights. Like Eck, I had the privilege of visiting Hsi Lai, myself as an invited instructor of Buddhist Ethics for a group of Whittier College students who had signed up to live and learn in the temple for a week over winter session. That was in 2010, many years after Eck’s visit in 1991, and her subsequent chronicling of the rise of the beautiful temple.

That rise, it would turn out, mirrored that of many early Buddhist temples in the U.S.: a population of Asian immigrants yearning to continue their Buddhist practice, a dominant Caucasian culture suspicious at best and racist at worst of those Asians and their religion, and the conflicts that would follow as the Asian Buddhists tried to enjoy their right to free exercise of religion. Luckily, after a rocky start, the Buddhists’ initiatives to win over their neighbors won out and the temple remains a stunning icon in the Los Angeles religious landscape.

Her chapter continues by chronicling how Buddhists in America approach the 3 refuges, or 3 jewels: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. In doing so, she weaves in the difficulties that non-Buddhists have had with Buddhism: “If Buddha’s not your God, who is?” Indeed she cites the gathering of the Parliament of World Religions in 1993, where Buddhist delegates, no doubt somewhat exasperated by the talk there of many faiths – one God, issued a statement reading:

…leaders of different religious traditions define all religions as religions of God and unwittingly rank Buddha with God. We found this lack of knowledge and insensitivity all the more surprising because we, the religious leaders of the world, are invited to this Parliament in order to promote mutual understanding and respect, and we are supposed to be celebrating one hundred years of interfaith dialogue and understanding!

Along with this basic misunderstanding of the Buddha by others, Eck writes of the many understandings of the Buddha within the Buddhist tradition, all represented alongside one-another here in America.

From this insider’s division of understanding, Eck moves on to an outsider’s typology with sections running in a rough chronological order based on appearance in the U.S.: The Chinese in America, Japanese Buddhists in America, The Pioneers (early European Americans who adopted and adapted the religion), and onward… All, or at least nearly all, of the “big names” in American Buddhism are represented, from Anagarika Dharmapala and Soyen Shaku to Paul Carus and Henry David Thoreau and Helena Petrova Blavatsky; D.T. Suzuki and Jan Chozen Bays, Jack Kerouac and Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Mahaghosananda, Henepola Gunaratana and Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzberg and Sylivia Boorstein, and of course Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama along with at least a dozen others.

Close to home, Eck – a fellow Montanan – writes eloquently of the particular difficulties faced by the earliest Buddhists in my home state: Chinese who had followed the gold rush and copper kings to towns like Virginia City and Butte, MT. That, however, is a rich story best saved for another time.

She concludes where she started, zooming out a bit as a scholar does, suggesting that we might think of Buddhism in America as still dominated by a divide between “Asian Buddhism and Euro-American Buddhism or …. old Buddhists from Asia and new Buddhists from the West” (p.216). However, on the same page she rightly notes “No simple paradigm can adequately categorize the many Buddhist communities of America.”

And that is, indeed, where we are left today. While the story of Buddhism in America has always been one of interaction, adaptation, compromise, and at times conflict, it is a story which, for the time being, defies any attempt at a master narrative.

In all, Eck demonstrates her superb abilities both as an academic and as a story-teller.

What are your thoughts on Buddhism in America, academic efforts to understand it, and/or the future of the religion here? Add your comments here for others to read and discuss and if you have a blog, please consider writing a full post on the topic and sharing the link here in the comments section.

Some older posts on the topic:

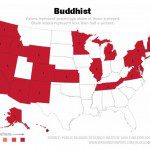

Mapping Buddhism in America (Feb 2015)

Buddhism dominates Western States behind Christianity (Jan 2014)

– “Painting the West Saffron” by Jeff Wilson at Tricycle (June 2014)

What does Buddhism in America Mean to You? (July 2013)

Race in American Buddhism – Earthlyn Zenju Manuel interviewed by Sam Mowe at Tricycle, a discussion here (Nov 2011)