“You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them.” – Charles Dickens, Hard Times

That human beings long to fly tells us far more about humanity than the fact that they walk on two legs. That teenagers daydream about the anarchy of a “zombie apocalypse” is a greater insight into their essential disposition than the fact that they use Facebook. A man is best known, not by what he has, but by what he dreams of having, for what he has is mere fact, the bare bricks of his existence, while what he dreams is castle, cathedral — those selfsame facts now testifying to the creative working of the human spirit.

Which delivers the Vincent Van Gogh best, his biography or his Starry Night? The first relays the facts of his existence. The second relays his personal, spiritual encounter with these facts. The first says “he looked at the stars.” The second is his look at the stars. To read the biography is to know about Van Gogh. To gaze at his Starry Night is to encounter Van Gogh, to glimpse, not facts-about, but the personal presence of the artist mediated through the work of art, which serves as a beautiful, near-eternal encapsulation of his relation to the world, to the stars, to the trees.

What is a human life if not a relation to the stars and the trees — and everything else?

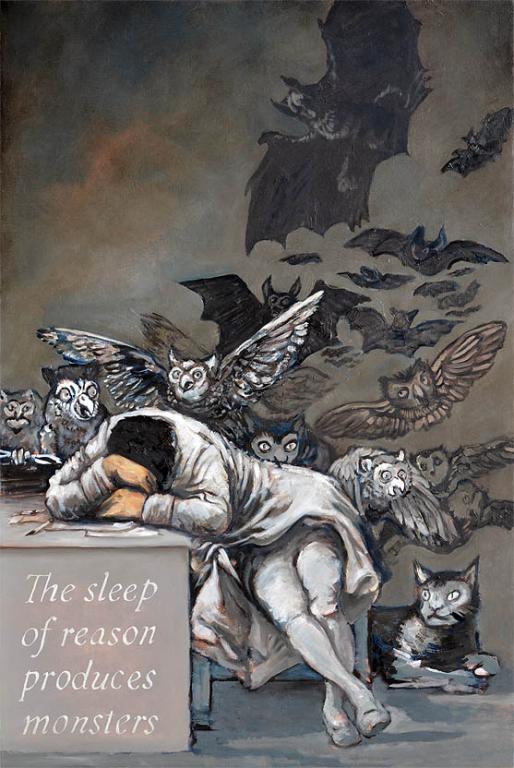

Don’t believe the man who scoffs at dreams. Pity him — his heart is failing. It will end by corrupting his head. Who can teach him that fantasy may be realer than realism, that the gods and goddesses of Ancient Greece give us a far more realistic insight into the minds of that race than any account of their laws, purchases and battles. In my upcoming book, I discuss how the facts about time — how our brains decipher duration, how we historically have parsed out the hours — is a poverty of information compared to our dreams of time-travel, our Doctor-Who-haunted fantasies of repeating the past and anticipating the future. These dreams reveal the workings of the human spirit on what is given. They are castles built from facts. Myths of time-travel grants us a fuller picture of a truly human experience of time, thick as they are with human presence — and human experience is the foundation of all scientific knowledge and rational fact.

Why do those grave men concerned with the eternal maintenance of a tyranny of Fact almost unswervingly end up writing books arguing, in one way or another, that facts and scientific knowledge are really “just as good” as myth, as fulfilling as legend, as wonderful as fantasy, and as exciting as a bedtime story? Why did Richard Dawkins write that bizarre children’s book — The Magic of Reality? Why did he begin his attack on all things irrational in The God Delusion with a reflection on the poetry, the romance, and other empirically unverifiable qualities of biology?

Perhaps they, like the poets in medical journals, like flexing that typically scientific hidden flair for literature. Perhaps — a hidden guilt. For all scientific investigation begins and ends with human experience. Our daily encounter with things is the source of even the most distant laboratory work — its source and final judge. And our daily experience is personal, mythological, religious, value-charged, moral, poetic, so far from merely factual that an objective view, a scientific method is not a life but a discipline of life — a deliberate and fastidious narrowing of experience into empirical categories. This reductionism is the success and glory and truth of science — it will never be the glory of life.

Dream on, then, like the realists you are.