Respect for other beliefs, tolerance of other religions, acceptance of other cultures — these doctrines are usually sugar-sweet forms of violence. This seems to me the only adequate explanation as to why our age is simultaneously respectful and racist; liberal and segregated; proud of diversity and incapable of actually enjoying diverse company outside of mandatorily diverse institutions — a schizophrenic personality that imagines itself open to the Other in all her differences while fearing, more than most things, any actual contact with the Other.

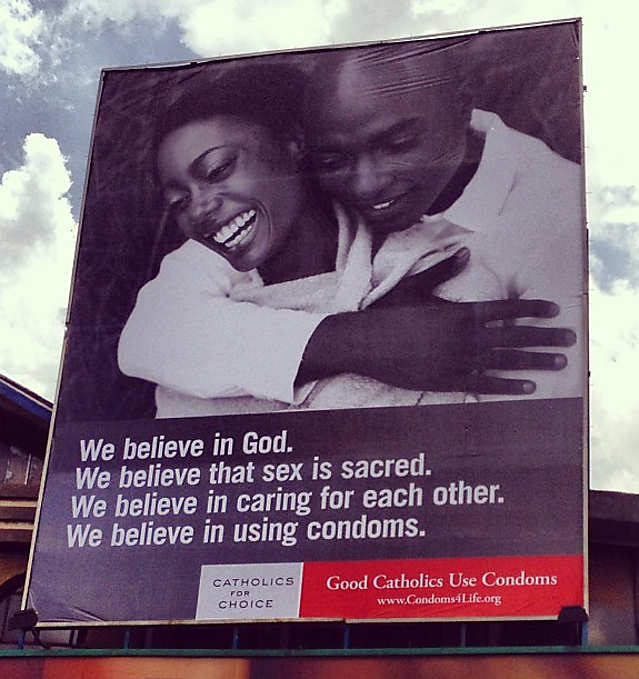

When someone tells me that they respect my Catholicism and my “right to believe what I want,” or that, while not agreeing with me, they celebrate the diverse viewpoint my “cherished religious convictions” bring to the community — this usually indicates that they have stripped, reduced, and re-fashioned me into an image they can bear.

See, I came declaring myself a Believer in that obnoxious, loudmouth pride unique to the Catholic laity. Now, were this a healthy planet, the human with the misfortune of being in the way of my evangelical warpath might respond: “I’m not Catholic. In fact, you Catholics are moronic, drunk Pope-worshipers. Get the @#$ out of my pool.” This would be, officially speaking, an insult. But I would be highly tempted to wrap the other up in a big, fat Apostolic hug — his insult would meet me in my otherness. It would take me as Catholic. It would negatively affirm the difference I claim as my own.

Unfortunately, this is a timid, frightened, litigation-happy, and deeply respectful planet: Such a response is unlikely. Awkward silence in the face of a perceived difference is the go-to, and with the help of a few beers, a vocalized “I respect your right to your beliefs” might earn a trophy for trying.

But this “respect of my right to believe” does not take me as I present myself. It generalizes me until I appear acceptable. Everyone and anyone has a “right to believe something” — thus it is only insofar as I am re-construed as being like unto everyone and anyone else that I am “respected.” Everyone “has something to contribute to society” — and thus the tolerance of my “Catholic difference” as “contributing to society” is a tolerance of me only insofar as I am not tolerated in my specificity and particularity (the actual Catholic content of my contribution to society), only in my generality (as a type of being who contributes to society). This isn’t exactly high praise. Give enough generalization, I can tolerate Adolf Hitler — he’s an individual human being with a right to clean drinking water and his own deeply cherished convictions.

Insults may prickle, but compliments aimed at a sanitized, general individual “underneath” the actual, particular person, with her beliefs, her culture, her race — these are worse. They allow us to indulge the illusion that we are engaging with a diversity of people, that we are really living-with others, when in reality, we are masking our intolerance for our actual breathing, sweating neighbors by tolerating them as theoretical ideas — as “individuals with the right to their opinions.” We are unwittingly affirming the very ground of our intolerant, racist, and frightened nation, by setting up the conditions for freaking-out when we (or the children who follow our example) can no longer reduce the actual Muslim or Jew into an “instance of diversity.” Forced to deal with an actual person who believes particular things and asserts them as absolute, we may well find ourselves hateful, imposed-upon, awkward, and intolerant — we’ve never learned to insult each other. We’ve never learned to call each other “wrong.”

I don’t how we miss this fact, that it is precisely the insult that more confidently assures us that the other loves us, or, at the very least, that she is really encountering us, really attempting to see us in all our prickly individuality. When someone takes my faith seriously enough to insult it, calling me “brainwashed by priests” or laughing at my “Catholic guilt,” it’s precisely at this moment that I — still disagreeing! — feel a natural surge of affection for that other person and validated as being Catholic. Consider erotic relationships: When you can call your lover “handsome” — you’ve got something good going on. When you can call him a “lazy-ass waste of space” — you’ve got something great. Any guy could be “handsome,” but it is only within the context of a particular, honest, and loving relationship that he can be insulted. The insult gives testimony to the real, human relationship that takes away its sting and transforms it a sign of affection — a symbol for the fact that the other really loves you. Žižek points out something similar in his defense of racist jokes:

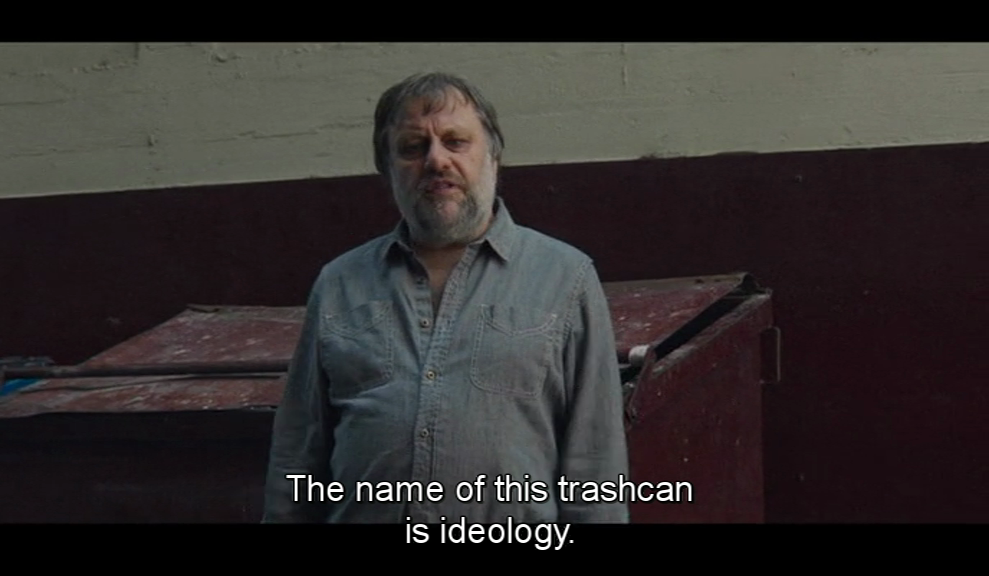

The solution [to racism] I think is to create an atmosphere or to practice these jokes in such a way that they really function as that little bit of obscene contact which establishes true proximity between us…I will tell you a wonderful story, a simple one. It happened to me a year ago around the corner here in the bookstore. I was signing a book of mine. Two black guys came, African-Americans, I don’t like the term. My black friends also not, because for obvious reasons it can be even more racist. But the point is and they asked me to sign a book and seeing them there I couldn’t resist the worst racist remark…When I was returning the books to them I told them you know, I don’t know which one is for whom, you know, you blacks like yellow guys, you look all the same. They embraced me and they told me you can call me nigga. You know when they tell you this it means we are really close. They instantly got this.

America can’t get over its racial divide, and it’s not just because of the kooks and the colonialism. It’s because no one can admit to enjoying being insulted, to finding a palpable sense of relief in that real, “obscene contact” where the other refuses to “respect you” by negating your race (considering you as a raceless individual or an “instance of diversity”) but by taking your race in all its differences, failings, and quirks, and loving you, not despite, but with it. Comedy is a healthy outlet for this — show me a white person that isn’t positively delighted by a black comic ripping into white “culture.” Everyone enjoys the opportunity to laugh at themselves, because it is always a simultaneous affirmation, a being-treated-as-oneself. (Obviously, this does not apply to any and all insults. Some insults are as much a sign of evasion and generalization as our timid tokens of “respect.”)

Now whether we can love each other without reducing each other into beings vague enough for love to be no great effort — it’s doubtful. We live in hypersensitivity over the possibility that we might offend, and our solution, up to this point, has been to isolate races, cultures, and religions into their mutual safe-spaces. Until we can realize that actually living-with and loving our neighbors looks way more insulting than this, we’ll just perpetuate violence, silence, and a national awkwardness.