Part 3 of a series beginning to see the light of day.

Summary of Part 1: If we desire our lives to be meaningful, we must be rid of sin, for sin is that-which-ought-not-be, and no meaning can be riddled with that-which-ought-not-be and remain consistent meaning, as no story can contain absurdities that contradict the entire story while remaining a good story.

Summary of Part 2: If our sins were merely concrete moments in an unreachable past, we’d all be screwed. If time was strictly linear, that is, if events in the past were truly past, gone and done-away-with, then we wouldn’t have a hope of meaningful lives or good deaths. We would die, narratives full of contradictions, stories chockfull of stupid, irrelevant prose, having done what we ought not do. But time is not linear in the person. It’s wibbly-wobbly. The person sums up the past in his present. The person exists as a relation to his past, and in every moment he brings his entire past into the present. This is hardly a mystical doctrine: When you deal with a person you deal with their past, because their past is present in them.

Thus we have reason to hope that our sins may be dealt with, for our past is in our present, and we can act in the present. By acting in the present, we may change the past, which exists as a relation to the present moment and to the whole of our lives. As Max Scheler argues in his book On the Eternal in Man:

“We are not disposers merely of our future: there is also no part of our past which…might not still be genuinely altered in its meaning and worth, through entering our life’s total significance as a constituent of the self-revision which is always possible.” (40)

and that since

“the total efficacy of an event is, in the texture of life, bound up with its full significance and final value, every event of our past remains indeterminate in significance and incomplete in value until it has yielded all its potential effects…Before our life comes to an end the whole of the past, at least with respect to its significance, never ceases to present us with the problem of what we are going to make of it…Historical reality is incomplete and, so to speak, redeemable.” (40-41)

What’s needed is not simply an erasing of sin. Such “erasing” is impossible. There is no forgiveness that utterly removes sin from our existence, our past, our memory, and our relations with others. There is no repentance that simply renders the space-time of our sin blank, a non-event that never was and will never effect us again.

What’s needed is not simply temporal distance between the moment of sin and the present moment. The past is present in the person. The past sin does not fade away any more than the language taught during childhood fades away, any more than the effects of parental love fade away, any more than the whole cornucopia of formative life-events simply cease being formative after so many years. Stab whoever tells you that “time heals all wounds” in the eye.

Temporal distance may provide us with the illusion that the past has been changed. We may, and often do, refer to our sinful self at the moment of sinning as “our old self,” as if the mere passage of time, the mere fact of an event being “old” actually constitutes another self, a someone-else who bears the guilt of sin — certainly not me, feeling happy and wholesome right now. Having willfully written an awful and absurd break in our narrative, we entertain the illusion that we have since started a new book. But this is patently false. We only have one life to live. We only have one story to write. The self is singular, it contains its past, and in the hours of night when our faults come flooding, there is no comfort in the pretense of a duplicated self, old and new.

What’s needed must be more than moral restitution. Doing good deeds may restore the multitude of fragmented and broken relationships caused by a particular sin, but the mere fact of good deeds do not dissolve indwelling sin. If your past contains an absurdity, it contains an absurdity. No attempt at making up for the absurdity by fulfilling some cosmic balancing act of good and evil will undo this existential fact.

So if sin cannot be erased, “gotten over,” or made up for, what’s to be done about the needling agony of ought-nots, the pain of containing within ourselves that-which-ought-not-be? What’s needed is repentance, that radical act of spiritual time-travel which alters the past by putting it in right-relation with the whole of life.

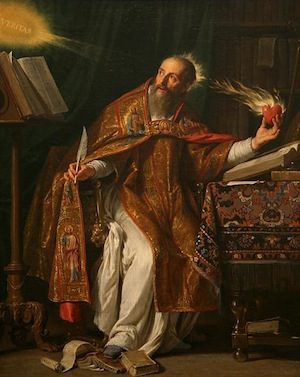

Consider two of our favorite sinners, Augustine and Adam.

When we read Augustine’s Confessions, even the most pious of Christians is content to hear of his sexual indulgences, his petty sin, and the generally crappy acts that present themselves as ought-nots dwelling within him, for we know that “the full significance and final value” of Augustine’s sins are revealed in Augustine’s entire life, in his conversion from sin to holiness. Augustine becomes Saint Augustine. On its own, Augustine’s sin is no more than that-which-ought-not-be. In the context of Augustine’s entire narrative, it is that from which came Augustine’s holiness. Because Augustine repented, the quality of his past sin is changed.

When we read Augustine’s Confessions, even the most pious of Christians is content to hear of his sexual indulgences, his petty sin, and the generally crappy acts that present themselves as ought-nots dwelling within him, for we know that “the full significance and final value” of Augustine’s sins are revealed in Augustine’s entire life, in his conversion from sin to holiness. Augustine becomes Saint Augustine. On its own, Augustine’s sin is no more than that-which-ought-not-be. In the context of Augustine’s entire narrative, it is that from which came Augustine’s holiness. Because Augustine repented, the quality of his past sin is changed.

Similarly, the Church calls the sin of Adam a felix culpa — a “happy fault.” How is this possible? Surely, Adam’s sin is sin, that-which-ought-not-be, miserable within him. How then, is his sin a happy sin? How does his sin — while still remaining a sin — undergo a qualitative change that makes it, not only bearable, but happy? It’s simple, really. Adam’s sin is called happy because it “won for us so great a Redeemer.” Adam’s sin has been woven into a narrative in which it becomes the ground and the reason for the saving action of Jesus Christ. “The full significance and final value” of his sin has been revealed to us, and it is Christ. His past sin is changed.

What’s needed to deal with sin, then, is an act that weaves our sins into the entire narrative of our existence, an act that qualitatively changes the nature of our past sin from an absurdity to an absurdity which serves as the fertile ground for our redemption — and therefore ceases to be absurd.

Repentance is characterized by a “repugnance toward the evil actions we have committed,” (CCC 1431) that is, an acknowledgment of sin as sin, as what-ought-not-be dwelling within us. It is neither justification nor erasing. It is not an eradication of our sins as life-events, but a dragging of our past sin into a new relation with the entirety of our life. This is why repentance entails “the desire and resolution to change one’s life.” (CCC 1431) If that-which-we-ought-not-have-done cannot be erased, it must be tied to a good which it subsequently serves, as ground from which the true life — the life lived as it ought to be lived, without the agony of the ought-not — blossoms.

Repentance is not only a turning away from a particular evil action, it is also, and primarily, a “radical reorientation of our whole life.” (CCC 1431) The human person, because he carries the past as present reality, reorientates his whole life, not just his present disposition. By pointing ourselves at the good with “the desire and resolution to change one’s life,” we point our past towards the good, we point our past sin towards the good, rendering it part of an overall upward strive towards towards a life well lived, and a damn good story, crippling it of its power to simply sit and breed guilt, a contradiction within us.

A sin is absurd. A sin considered as the grounds for redemption, reconciliation and forgiveness makes sense. It is transubstantiated into the precondition of a reconciled life. It becomes a part of a whole movement towards the good, a dark and painful chapter of an overall return to God, a return that consoles the painful by giving to it a sweet, final meaning, like a dawn that makes the dark but a canvas for the glory of the day. Sin is stripped of its power to hurt us, because it has been made the stepping-stone on path reorientated towards the good, towards what ought to be. Through repentance, our past evil actions bow and serve the good. Through repentance, every fault becomes a happy fault.

So be sorry for your sin, with the resolve to be good, and you will have changed the meaning and the significance of your past.