I’ve been reading Brideshead Revisited lately. It’s one of those ubiquitous novels that everyone carried around and fawned over at the university I attended, and that I consequently refused to read or even acknowledge as literature.

I wasn’t Catholic then, after all, and even after I became Catholic it took me a while to realize that most Catholics actually have a true appreciation for art. At least at UD, it wasn’t like being in Evangelical circles where the latest book written from a purely Evangelical perspective, or one of the million perspectives, is heralded as “the best achievement in the written word since the Bible.” The Left Behind series, for example, were at the top of my “favorite works of literary genius” for most of middle school, second only to Twelfth Night, which I patently did not fully understand and loved primarily because none of my peers or teachers could understand a single sentence but thought I was brilliant for reading and re-reading.

I’ve come to realize that there is a bit of that “Catholic literature is the only literature even if it’s horribly written because it’s at least true and not smutty or worldly” attitude among some circles, but it’s not prevalent among the circles I run in. There’s this amazing thing about Catholicism where our highest calling is to the Truth. So if we find truth in, say, a smutty Shakespeareian play or a bawdy Chaucerian tale, we can still love it for the truth it carries instead of rejecting it wholly because it doesn’t conform to our understanding of how life should be lived. Or, God help us, because the authors weren’t “saved”.

So after I got off my high horse about “Catholic novels” and actually considered that maybe some of my college friends who chose Brideshead Revisited for their senior novel weren’t just narrow-eyed zealots, I picked the book up myself. It’s been slow going, mostly because I’ve spent the last few years avidly soaking up the written equivalents of trashy soap operas, but also because we’ve been moving and stuff. And my reading of Brideshead was unfortunately interrupted by the intrusion of The Hunger Games. (I have no excuse for myself)

But this last week I’ve really gotten into the novel. I’m nearly finished with it, and last night read the passage where Julia has this religious crisis by the fountain after Brideshead candidly acknowledges that she and Charles are living in a state of mortal sin.

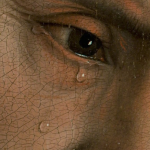

“Living in sin, with sin, by sin, for sin, every hour, every day, year in, year out. Waking up with sin in the morning, seeing the curtains drawn on sin, bathing it, dressing it, clipping diamonds to it, feeding it, showing it round, giving it a good time, putting it to sleep at night with a tablet of Dial if it’s fretful. Always the same, like an idiot child carefully nursed, guarded from the world. ‘Poor Julia,’ they say, ‘she can’t go out. She’s got to take care of her little sin. A pity it ever lived,’ they say…Mummy carrying my sin with her to church, bowed under it and the black lace veil…Mummy dying with my sin eating at her, more cruelly than her own deadly illness. Mummy dying with it; Christ dying with it, nailed hand and foot…”

As I read that passage, something clicked. I suddenly understood what that phrase meant, Catholic guilt. Not just abstractly but deeply, personally.

I didn’t know many Catholics growing up, and the few I did know were whispered about behind hands as they passed, always with the surprised cry of “But they seem so normal!” coming after. It wasn’t until UD that I even heard the phrase Catholic guilt. Then, and for a long time afterward, I snickered at the idea. Catholic guilt, I thought, please. These people have no idea what true guilt is. There they go, off to confession, where they think a man in a box can wave a magic wand and make all their sin go away. How could they feel guilt? All they have to do is say some magic words to a magic man and feel better. No, I know what true guilt is. True guilt is knowing that you are a snow-covered dung hill. True guilt is knowing that nothing you do can take your sins away, or even stop you from sinning, or even accept grace. True guilt is knowing that you’ll die in your miserable sin unless you’ve been predestined.

Oh, how wrong I was. That wasn’t guilt, what I felt then. Not even remotely. It was despair, and elation, and absolute disconnect from responsibility for my actions. It was being bound, hand and foot; knowing that nothing I did or didn’t do made the slightest bit of difference, eternally; that either I really meant it when I prayed the sinner’s prayer or I didn’t, and even if I did, it wouldn’t have mattered unless I was chosen. It wasn’t guilt, it was loss of freedom. Loss of autonomy. Loss of everything that God gave us as humans. Loss of human dignity.

Two years ago a chance conversation with some friends ended with me in something like a crisis of faith. Even though my confirmation was nearly five years ago, the conversion is ongoing. That conversation was the first conversation in which someone looked me in the eye and said, “Yes, you could go to hell for that. Even though you’re generally a good person. Even though you don’t use birth control. Even though you pray. Yes, if it’s a mortal sin and you die in that state, you could go to hell. Mostly likely you will. We can’t know the mind of God; we can only know the state of our own soul.”

I had never before considered the possibility that I might go to hell because of my own failings. Growing up, and especially in college, I wavered between being certain of my own justification and terrified that God didn’t want me. One part of my mind knew that my sins were too great and ran too deep for me to have truly been re-born, for the Holy Spirit to truly be dwelling in me and guiding my actions; after all, how could something holy dwell in someone so fallen? That part of my mind I usually managed to wall up and ignore; but occasionally when I fell into a kind of spiritual torment I would eventually end up at the inevitable conclusion that either God did not love me and did not want me, or He just hadn’t saved me yet. Usually the latter was enough to allow me a few hours of sleep, but not always.

But now. Now, it became clear that while grace was offered to me, while salvation was within my grasp, I must reach out my hand. I must put away myself, my own desires, my own faults and failings and disordered loves and choose, minute by minute, to accept grace. And when I turned away, the fault was on my own soul. When I rejected God, He would let me. After all, one of the greatest gifts the Church has given me is the recognition of my own free will. What good is a will if one is locked into a choice? It doesn’t follow. It isn’t rational. It isn’t true. No one is saved once and saved forever. God gave us a will, and out of His infinite and astounding love for us, allowed us to choose or reject Him. Not once, but forever. Every minute. And He will never, ever violate our choice, because to do so is to violate our essential human dignity. The very essence of who we are. If I live a good life, even a remarkable life and then turn away, today, shut my heart and soul away from God, and die tonight, then He will let my choice stand. How could He not? It’s one of His many gifts to us.

After that night I spent a few weeks literally refusing to pray. I couldn’t accept it. It took me a while to get my head around it, to understand it, and to see that it isn’t cruelty on the part of God, but kindness. Love. Mercy. Justice.

But after those rough weeks, something new set in. Catholic guilt.

Now I understood the heaviness of the thing. The weight of the freedom to choose. The great responsibility that came with it. And the absolute necessity of leaning on the sacraments. Without those, without that grace, I would be lost. Who can bear up under the weight of their own sins without Christ standing beside them?

But I didn’t understand it as such. I felt it, but didn’t name it. I knew that things were different, that life was harder, that I was sad more often when my sins stacked up, that I dreaded confession like I never had before but also that I needed confession more than ever. Cleanness is something you can feel in your soul. Forgiveness is a heady thing. And the joy of the Eucharist is unparalleled.

It wasn’t until I read that passage, though, that I got it. I got why Catholic guilt is legendary throughout the world. I understand now why even non-Catholics see it as something wholly different than the guilt of other religions, other systems of belief. I understand why the weight of Catholic guilt can literally wear a person down, why running from one’s sins is utterly impossible after understanding truth, even understanding it a little more than one did a year ago, and why there is such a hatred for the Church from those who have left her folds.

Catholic guilt. The guilt that accompanies living a fully human life. That guilt that comes with knowing that those sins that Christ bore for us are not out of our control, that we aren’t fallen and evil, that we have the choice, that we’ve always had the choice. The ability to choose good over evil. It isn’t out of our control. It isn’t the Spirit working through us. It is an act of the will…a wounded will, to be sure, but nevertheless an essentially free will.

And I understand why so many of my friends love Brideshead Revisited. After all, it is only through the uncomprehending eyes of Charles Ryder that Catholicism becomes clear in all it’s facets. The wonder of it, the terror of it, the reality of working out one’s salvation in fear and trembling or going mad trying to run away from it all. And a little, childish part of me feels sorry for us. Our cross is so much heavier to bear. But mostly I feel deeply grateful to have been brought into the folds of the Church, where there is such truth and goodness and beauty and yes, heaps and heaps of Catholic guilt.