This post has been a long time coming. It’s actually been well over 2 months since the Homerathon, and my original intent was to write this post the day after the Homerathon, but alas. Various circumstances of life intervened.

All those various circumstances don’t account for the long, long time that elapsed, though. Here’s what that procrastination boils down to: I’m not a huge fan of Homer.

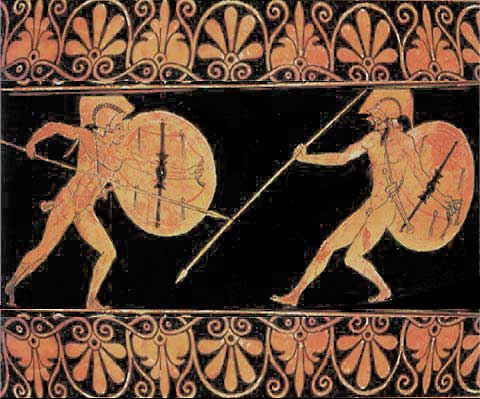

It’s a total English major faux pas for me to admit this, but the Iliad regularly put me straight to sleep during Lit Trad I. It was the first book in my entire scholastic career that I didn’t finish. (Don’t worry, it was soon joined by all of Henry James). For a war poem, it sure was boring as all hell. The only part I liked was Hector and Andromache’s emotional farewell.

But when I was reading book 18 for the Homerathon, I kept thinking, “I don’t remember this book being any good. But it is good! It’s really good, in fact, and not boring at all, and not nearly as clunky and cumbersome as I remember. It’s even poetic. I actually understand now why it’s considered epic poetry. I kind of want to read the whole thing again now. For the first time.”

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the difference a translator can make.

Stanley Lombardo translated this version of the Iliad. Being utterly unfamiliar with both Greek and the Iliad, I can only surmise, based on his own admissions in the introduction and my surprise pleasure in reading it, that he took some liberties with the text to make it not mind-numbing to wade through. And thank God for that.

Poetry is important to me. Rhythm, meter, and word choice matter. And when I was presented with a book that is supposed to be the poem upon which all other poetry ever has been built, and it read like a non-native English speaker attempted to write it using the meter of his original language, and then just never stopped writing, I wasn’t impressed. I realize that every classics major and English major and anyone with a rudimentary grasp of Western Civilization is gasping in horror right now, and rightly so. I should probably brace myself for an unpleasant conversation with my father-in-law later. Granted, I should have looked beyond the prosaic and endlessly endless catalogue of ships to see the greatness, but I didn’t. Mostly because I was (am) a lazy reader. Also, because I was eighteen and had important 40’s nights to attend. In my defense, no less a critic than Horace claimed that, in the famous (translated) phrase, “even Homer nods.”

But this Iliad is something new. Something beautiful. Something-dare I say it?- glorious. Stanley Lombardo himself came to Ave Maria for the Homerathon and read the final book. I missed half of it (because Lincoln, that’s why), but I was there for the very beginning and the end. At the beginning, he walked up to the microphone with a hand-held drum and I inwardly cringed and readied my best “I’m genuinely enjoying this and not at all pretending because I don’t want you to feel embarrassed” face.

Shockingly, I didn’t need it. It was amazing. He completely captured the ragged, hypnotic, haunting rhythm that I imagine the original Greek had. And even if it didn’t have that (which it probably didn’t, because I’m given to understand that Greek is a much more fluid and musical language than ours), Lombardo used the unique cadence of modern American English to fashion something so remarkable that I understood for the first time how people could listen to someone tell and re-tell this poem, for centuries. I didn’t want him to stop reading. I could have listened to it for centuries.

(Unfortunately I couldn’t get the videos taken here at Ave formatted correctly, so this is a Youtube video of Stanley Lombardo reading from Book 12, I believe. It’s really long, but if you want to hear how effective the drum is, he starts using it around 37:30.)

At the end, he re-read the final lines in the Greek and I got chills up my spine. It was almost mystical, the way thousands of years seemed to fold together and I felt as I imagine the Greeks must have, listening to this blind poet weave an achingly magnificent tapestry of a poem using their own history and their own words.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NssnanW93fI(Here is Stanley Lombardo reading Book 1 in the original Greek.)

But what made it magnificent was that Stanley Lombardo had actually managed to bring it to life in a new language and a new time. Translating poetry has always seemed to me an impossibly tricky task, because poetry is an inextricable union of words and meter. A poem’s meaning cannot be found in the words alone. How those words are strung together is equally as important, if not more important. There is no single word in one language that will perfectly correspond to a single word in another language, nor can the way we speak those words, the inherent pauses and lengthened vowels and the everyday rhythm of our speech, easily be replicated in a foreign language. Trying to convey the poet’s meaning while also transmitting any sense of the rhythm and meter is not a task I envy anyone. I love what Stanley Lombardo says in the introduction about the way he managed this difficulty:

“Homer’s language does not correspond to any form of Greek ever spoken. It was a poetic dialect developed over generations of performance — rich, flexible, and capable of producing a wide variety of musical and semantic effects. It has often been observed that in the late twentieth century there is no longer available any traditional poetic language for translation of epic — or for writing English or American poetry for that matter — that we must content ourselves with the diction of prose cast into verse of some kind, and that we cannot therefore hope to achieve in translation the epic grandeur of Homer. I do not think there is much truth to this. What is true is that the use of an artificial poetic diction would serve to embalm Homer rather than bring him to life. But English and American poetry contains vast resources that are available to the translator; these resources include a modern poetics based on natural language that, far from being prosaic, is capable of great energy and beauty. A successful translation, especially of a work on the scale of the Iliad, must grow out of the poetic tradition of its own language and become one of its current embodiments.”

I’d say he managed an extremely successful translation. And organizing the Homerathon, a 24-hour-long reading of the Iliad, was a stroke of brilliance by Ave’s Dr. Travis Curtright. The students (and random professor’s wives like me) got to see and hear Homer in a way that made it alive to us. Not some clunky, inaccessible relic of a past age, but a living, breathing, thrilling poem of war and violence and the sins of man, all told in the familiar cadence of our own language.

One of the students stayed for the entire 24-hour reading (and yes, that was 24 consecutive hours). She had this to say about it:

So I never actually read the Iliad when I was supposed to freshman year… I was one of THOSE students who just barely passed by just because I was good at deductive reasoning and took good notes. The reason for this was because I found the Iliad so difficult to read. It was so dense that I didn’t see the point in my trying to keep up (I am a very slow reader). However, after staying up all night and hearing the entire book read aloud, I realized how very wrong I was. I actually enjoyed it! (Crazy! I know, but it’s true!) Hearing it and being able to follow along in Dr. Curtright’s copy made the whole thing come to life. It was like a play, which, I am told, was the point.

I can’t express how much I love things like this. A new translation that brings life to poem that has grown rusty in the effort to bring it from Greek to English. An unorthodox event that gets the students all giddy (because what college student doesn’t love all-nighters?) and then shows them what this poem was meant to be, what it was, and what it still is. Students who stay and listen to 24 hours of reading aloud. Students and professors who goof off and have fun with the reading, making it their own. These T-shirts:

It’s just all so awesome. And it’s moments like these that really show students that this rich, amazing heritage of Western Literature that we’ve inherited is a whole lot more than dusty books on a shelf. It’s a living, breathing part of us, woven into the words we speak and the way we speak them, with the same eternal themes echoing again and again as we grapple with them. Whether it’s the Iliad or Platoon or The Things We Carried, war and violence are part of our inheritance as humans. But no other work of art has reflected on it as completely as the first. It’s remarkable to see it brought to life again after all this time, and to see a new generation of youth embrace it.