Jeremiah! The man, the book, the bullfrog…

Jeremiah is the second longest book in our longest book of scripture. (Only Psalms is longer). We know more about Jeremiah than any other Old Testament prophet, because for reasons unknown, much more biographical information is included. First, though, the setting. We are now in Jerusalem, c. 625 BCE. Josiah the reformer has been on the throne for 15 years. Israel is technically an Assyrian vassal but under the direct administrative control of Egypt. Lehi is either at his Jerusalem residence or north of Jerusalem at his ancestral home. We have a lot of sources on the events of this time, and one of the best ways to get a handle is to read the essays in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, also available online. I also suggest reviewing the history in 2 Kings 22-24.

Jeremiah himself was from a priestly family in Anathoth, a small village 3 miles N.E of Jerusalem. We know several things about his life; it was… hard. He was accused of treason, thrown in jail and in pits, divinely commanded not to marry or have children (since they would just die horribly anyway), and felt very alone and abused by God. He laments his life and calling, and dies after Israel is destroyed and he is hauled away against his will to Egypt by surviving Israelites. One book I have on Jeremiah has a section called A Sense of Impending Doom, which opens with “One of the most distinctive features of Jeremiah’s prophecy is the acute sense of impending disaster that informs much of his poetic oracles.” In that light, here’s an appropriate soundtrack for the Book of Jeremiah.

On the positive side, chapters 36-38 tell us about Jeremiah’s scribe Baruch, a close (and only?) friend. As is likely with other prophets, Jeremiah himself did very little, if any, of the writing of his prophetic sermons. Orality was the main form of communication, and writing was not terribly significant for the vast majority of the population. (See here, first few sections.) Baruch, at least, is named and mentioned. Other disciples/memorizers/scribes/”tradents” who orally preserved and shaped the teachings of past prophets are simply anonymous.

Jeremiah’s Temple Sermon

Like a lot of the Old Testament, the Book of Jeremiah is not really chronological.

Whoever was responsible for the book of Jeremiah did not arrange its contents chronologically. This causes consternation on the part of some readers. Indeed, no theory about the process of the book’s composition has reached consensus among interpreters. One can point, however, to subunits within the book that are collections of traditions united thematically (e.g., chs. 2–20; 27–29; 30–32; 37–44). Readers will often recognize links (both verbal and thematic) between proximate chapters, even if reasons for the structure and arrangement of the book as a whole eludes them.- NIV Application Commentary

So Jeremiah jumps around and sometimes repeats. For example, chapter 26 is actually a restatement or a different account, of what’s called Jeremiah’s Temple sermon. Chapter 7 is the other place this is set forth. It’s one of my favorite chapters, and it dovetails nicely in some ways with the Book of Mormon. Chapter 7 contains more of the actual sermon, and chapter 26 reduces it to a paragraph or so but provides a lot of context.

Jeremiah is commanded to go to the gate of the temple complex, the equivalent of the gate to the temple parking lot. There is a tradition that worshippers “were greeted at the temple gates by a servant of the institution, who asked them to examine their moral lives prior to passing through the gates and participating in the worship.” (Word Biblical Commentary. On that tradition, see here.) Perhaps Jeremiah was fulfilling this role.

At the gate, he is to preach in a particular way. Jeremiah has to convince the people to repent and undermine one of their beliefs, namely that the true temple of the true God in the holiest city on earth means complete and utter protection from enemies, that Jerusalem cannot fall. (Think of Laman and Lemuel’s protestations here, that Jerusalem was righteous and could not be destroyed.) They are, so they think, protected and justified in their actions, though contrary to God’s command and the covenants they have made. For the Israelites, in some way, the edifice, the establishment symbolized by the magnificent temple at the peak of the capital city, guaranteed their righteousness and subsequent protection.“…the people flocked to the temple, confident that their violations of the divine code were of little moment to the deity and that, as it were, the wonderful temple covered a multitude of sins!” (WBC again) Certainly God would never allow his city let alone his temple at its height to be destroyed. Jeremiah launches a frontal assault on this belief with both logical and historical arguments.

Here I quote some short verses from chapter 7, words Jeremiah spoke in the temple gate. (Jesus quotes v. 11)

Thus says the Lord of hosts: Amend your ways and your doings, that I may dwell with you in this place. 4 Do not trust in these deceptive words: “Temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord!” 5 For if you truly amend your ways and your doings, if you truly act justly one with another, 6 if you do not oppress the alien, the orphan, and the widow, or shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not go after other gods to your own hurt, 7 then I will dwell with you in this place… 8 Here you are, trusting in deceptive words to no avail. 9 Will you steal, murder, commit adultery, swear falsely, make offerings to Baal, and go after other gods that you have not known,10 and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by *my* name, and say, “We are safe!”—only to go on doing all these abominations? 11 Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your sight? You know, I too am watching, says the Lord. 12 Go now to my place that was in Shiloh, where I made my name dwell at first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of my people Israel. 13 And now, because you have done all these things, says the Lord, and when I spoke to you persistently, you did not listen, and when I called you, you did not answer, 14 therefore I will do to the house that is called by my name, in which you trust, and to the place that I gave to you and to your ancestors, just what I did to Shiloh.

Shiloh, as you may recall, was the place the tabernacle had been set up in the days of Eli and Samuel, about 30 miles north of Jerusalem, as found in 1st Samuel 1-4.

If the people thought God’s temple guaranteed God’s presence and inviolability, Jeremiah says, they should go check out Shiloh and see what happened there.

[Shiloh] too had been a place where God’s presence was established, but now it was in ruins. The reason for ruin was equally clear to the prophet, for its demise was “because of the evil of my people” (v 12). A temple or shrine, in other words, which was the symbolic location of God’s presence among his people, provided no absolute security; God could be driven out of his temple by evil, and when that happened, sooner or later the place would collapse in ruin. Thus, Jeremiah drew upon the resources of contemporary “archaeology” to drive home his point; the stones and ruins of Shiloh, only a few miles north of Jerusalem and known no doubt to the prophet’s audience, had a story to tell. (WBC)

Jeremiah wants the people to have no illusions about the mere presence of the temple. Unless they change their behavior, Jerusalem and the temple will become like Shiloh. Now note, these people being rebuked were the ones entering the temple, not the ones staying home! At least in theory, these were the righteous people making the required sacrifices. Jeremiah doesn’t have issue with them carrying out their religious rituals, as much as the other things they’re also doing (offering sacrifice to other gods as well) and the things they’re omitting (e.g. acting justly one with another, not oppressing the foreigner, the orphan, and the widow).

It all sounds very much like some of the things we read in the Gospels, as well as problems we have today. Simply because we wear our white shirts and dresses and attend our meetings and the temple does not mean we are safe and secure against spiritual ruin, particularly if we are living our lives inconsistently with our covenants and commitments. I doubt any Israelite actually verbalized “Hey, I can totally steal and kill and oppress the foreigner, cause I live in Jerusalem with God’s temple”… but that is effectively how they were thinking and acting.

Jeremiah’s Call

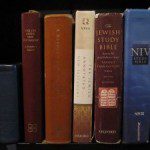

I have two notes here. First, most of us have to read the Old Testament in translation. For English-speaking saints, that most often means the King James Version. There’s no reason why LDS can’t study other translations as well, of course, and the various issues with the KJV are well-known. (See this packet of articles.) However, no translation can perfectly convey what the original author appears to have meant for any but the simplest sentences. Many of the subtle and not-so-subtle connections or messages the text is trying to communicate are lost in translation, because we need more than just the words.

Jeremiah 1:11-12 is one such thing, as it recounts a vision of Jeremiah. “Moreover the word of the LORD came unto me, saying, Jeremiah, what seest thou? And I said, I see a rod of an almond tree. 12 Then said the LORD unto me, Thou hast well seen: for I will hasten my word to perform it. ” What possible connection is there between the almond tree and God’s reliability in carrying out his word?

When limited to English translation, one might surmise almond trees were symbols of reliability or were particularly resistant to change. In actuality, almond trees had no such symbolism. Instead, there is a Hebrew pun here. Jeremiah reports that he sees a shaqed (“shah-cade” or almond tree), and God replies that he will shoqed (“show-cade” or watch over, assure) his words. So there are things going on in Hebrew that simple English translation can’t capture, and for that we either need to learn Hebrew or use a study Bible with explanatory footnotes.

The Jewish Study Bible says, “11–12: A pun upon the word “shaked,” almond tree, and “shoked,” “watching.” The almond tree is one of the first trees to blossom in the spring, signifying God’s resolve to bring about the divine word concerning Jerusalem and Judah” and goes on. The NET Bible says “There is a play on the Hebrew word for “almond tree” (שָׁקֵד, shaqed), which blossoms in January/February and is the harbinger of spring, and the Hebrew word for “watching” (שֹׁקֵד, shoqed), which refers to someone watching over someone or something in preparation for action. The play on words announces the certainty and imminence of the LORD carrying out the covenant curses of Lev 26 and Deut 28 threatened by the earlier prophets.” (For more on this kind of thing, see part 3 of my Sperry presentation.)

Second, Jeremiah’s call says in good poetic parallelism,

Before I formed you in your mother’s womb I chose you.

Before you were born I set you apart, I appointed you to be a prophet to the nations.

This has often been read by LDS as referring to a doctrine of pre-mortal existence. However, it’s far from certain that this doctrine had been revealed to or commonly understood by the Israelites. On this, then, see Dana Pike, Divine Election in the Ancient Near East and the Anchor Bible Dictionary article on “Soul, Preexistence of” which was authored by LDS scholar S. Kent Brown.

As always, you can help me pay my tuition here. You can also get updates by email whenever a post goes up (subscription box on the right). You can also follow Benjamin the Scribe on Facebook.