Today we are rushing through Daniel AND Esther, although next week is devoted solely to Daniel 2. What’s interesting is how the comparison between Daniel and Esther actually serves the manual’s purpose, which is to “help class members have the courage to live according to gospel standards.” How so?

Daniel doesn’t hide his Jewishness, even being a bit extravagant, while Esther is apparently able to pass, to fly under the radar as a non-Jew. Significant, perhaps, that

“noticeably absent [in Esther] is any mention of God or of religious observance (prayer, Jewish dietary restrictions, traditional modesty, and endogamous marriage).”-The Jewish Study Bible.

Indeed,

“there is no mention of Jerusalem, the temple, the law or the covenant as is found in other postexilic books.Unlike the book of Daniel, which also is set in the court of a pagan king, there are no prayers, apocalyptic visions or miracles….Esther shows no concern for the dietary laws when taken into the court of a pagan king, she conceals her Jewish identity, and she pleases the king in one night more than all the other virgins. When she risks her life for her people, she does so only after Mordecai points out that she herself will not escape harm even if she refuses to act.”- Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry, & Writings “Esther, Book of.”

Thus, Esther seems quite assimilated, by comparison to Daniel. (Some have wondered if this is the reason Esther is the only book that has not been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls biblical texts.)

These are two different approaches to being a religious minority under pressure to conform, swinging between assimilation (or becoming more like the surrounding culture) and differentiation (becoming less like the surrounding culture). LDS sociologist Armand Mauss has examined how LDS have undergone these shifts in the US in his Angel and the Beehive: the Mormon Struggle with Assimilation. (Mauss has answered some good Q&A here, has also written on the priesthood ban in current discussions and race, giving one talk at FAIR that was also published at blacklds.org and Sunstone)

For a missionary-minded people, both extremes are undesirable: too much assimilation to the surrounding culture means someone looks at a Mormon member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and sees virtually no difference from anyone else; too much differentiation from the surrounding culture creates impressions of extremes, strangeness, cultishness, etc., and also is counter-productive. The trick is to stay in the center where a “productive tension” is struck, where Mormons we are different, but not too different; where those differences are attractive, but embracing them doesn’t require a complete break with mainstream culture. (Think Amish or Haredi as extreme examples of breaking with mainstream culture, perhaps.)

On to today’s passages.

Daniel–

The Babylonians imposed several exiles on Israel. Most scholars recognize three. The first two involved exporting upper-class, learned, skilled people to Babylon, and Daniel and companions apparently belong to this group. The Babylonians are skimming the cream of the cultural crop. (The third exile is the final one in 586, which involves destroying the temple and taking the majority of the people.)

Everyone knows the stories of Daniel, but few know the oddities of the Book of Daniel, which strongly suggest a much later collection of stories and traditions than a contemporary journalistic account.

- The language switches into Aramaic partway through (2:4-7:28 are Aramaic, with some Greek and Persian words as well.)

- Daniel is remarkably old. He is taken as a “youth”(1:4) in 3rd year of Jehoiakim= 606 BC (1:1) Let’s assume “youth” = age 14, results in a birth date c. 620 BC. Daniel is still around when Darius becomes king (Dan 5:31), c. 521 BC, making Daniel not a young man in the lion’s den, but a very old man.

- There are lots of historical mistakes, e.g. the mixup between Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus in 4, misunderstanding Belteshazzar in 4:5, and Darius the Mede in 6. (I disagree with the last two paragraphs, but this old Ensign article does a good job with the history of some of these mistakes.)

- Daniel, who stoutly refuses to give up any Jewish observances, is not thrown into the fiery furnace, only his three friends. So, where did he go in that story? Did he backslide? Or does this show that we have a collection of disparate traditions being pulled together?

A few notes on names and people–

Daniel &co. receive new names befitting their status as quasi-courtiers of Babylon.

- Abednego is AHbed-NEHgo (“Servant of Nego”?), not a-bend-igo. Ahbed like one of the main characters in Community.

- Daniel -> Belteshazzar means something like “protect the prince’s life” and has nothing to do with the Babylonian God Bel. This indicates that the author doesn’t speak the language, since the explanation in 4:5 as being named after the Babylonian God is incorrect.

- Shadrach and Meshach have not been able to be explained, either in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Babylonian.

- There is some variation between NebuchadNezzar and NebuchadRezzar. That letter change is probably just due to spelling variation, meaning “O Nabu, protect my first-born.”

- The Chaldeans are a group that showed up in Babylon around the 9th century BC. In the KJV, the language referred to alternately as Chaldean or Syriack is Aramaic. (Syriac is a much later descendant of Aramaic, used extensively by Christians.) The text also uses “Chaldaen” as a job/title of sorts, in connection with magicians, enchanters, sorcerers, wise men, and the like. “The Chaldeans remained an influence in the administration of affairs in the empire and seemed to have gained a reputation for wisdom and counsel throughout the Persian and even into the Hellenistic periods.” (ABD, “Chaldea, Place”) The king himself would have been a Chaldean, so in that list, it MUST be a kind of job title. Chaldea (or “land of the Chaldees”) is generally applied to the S. half of Mesopotamia throughout the Bible, although anachronistically, and this is a minor problem for LDS, as it appears in the Book of Abraham.

- “Eunuchs” appear throughout Daniel. Substitute “officials” instead, as they may or may not have been actual eunuchs but were definitely middle/high officials.

Now, Daniel’s first problem is one of food in 1:8. “But Daniel purposed in his heart that he would not defile himself with the portion of the king’s meat, nor with the wine which he drank: therefore he requested of the prince of the eunuchs that he might not defile himself.”

Note that the “meat” Daniel &Co. refuse is not meat; KJV “meat” always means “food,” which means that the (in)famous “milk before meat” philosophy is a baby analogy, “milk before solid food” (which implies that as adults we should all be eating “meat.”)

One of the questions here is how it would defile him. It’s not clear that this food violates kashrūt, the kosher laws, which would have been quite different than today’s kosher laws. Unless the king is serving pork all the time, which is unlikely, or serving very bloody meat. But Daniel finds the wine also to be defiling, and there’s nothing in biblical kashrūt about wine. Perhaps the meals had been offered/blessed by idols first. If so, it was very similar to the problems in 1 Corinthians with “idol meat.” But then why would “pulse” (lentils? vegetables?) also not have been offered/blessed by pagan deities? Why not just ask for the same food, unblessed? Is Daniel asserting his otherness, differentiating himself and Jewish colleagues from the Babylonians? That’s bold but potentially dangerous. And as noted in many places,

Daniel’s practice in this regard is strikingly different from that of Esther, who was able successfully to conceal her Jewish identity.- NET Bible First Edition Notes

To summarize the potential reasons why,

[1] The food may have been offered to idols. However, in Babylon only the king himself and a few senior temple officials could partake of food and drink that had been specifically offered to a deity.

[2] Daniel’s concern was to keep the Mosaic food laws about which animals could be eaten and how they were to be killed. This may be suggested by his request to be given vegetables to eat. However, the food laws did not apply to wine.

[3] The issue was the implication of assimilation to Babylonian culture and the pledge of loyalty to the king. However, presumably the vegetables they were given came from the king’s stores too. Maybe the difference was that they were not prepared in the king’s kitchens but by the Jews themselves.-ZIBBCOT

In any case, it’s clear that this episode has little to do with our modern Word of Wisdom per se (and to its credit, the manual avoids any connection.) The blessings of the Word of Wisdom are generally those of obedience, not natural health, and we keep it because of prophets, not because of rationalistic health effects. (See Julie Smith here for a great explanation of why that is problematic.)

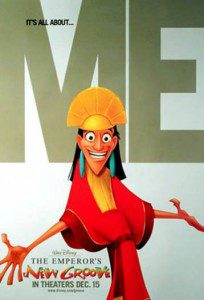

Daniel’s second problem is getting in trouble for not paying sufficient homage to the king’s idol in chapter 3. Funny enough, the golden idol everyone must bow down to (KJV “worship” usually means a literal bowing down) is more-or-less Daniel’s fault. In the vision in 2, the statue has a fine golden head. Daniel obsequiously says, “37 You, O king, the king of kings—to whom the God of heaven has given the kingdom, the power, the might, and the glory, into whose hand he has given human beings, wherever they live, the wild animals of the field, and the birds of the air, and whom he has established as ruler over them all—you are the head of gold!”

And the king naturally thinks, “Well, I AM pretty fantastic. A golden head, you say? How about an entire golden statue of me? And everyone has to worship it, just because I’m so wonderful? Yeah. Let’s do that.”

And this leads to Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-Nego (but not Daniel?!) being thrown into the fiery furnace for failing to worship it.

I think one of the best lessons in Daniel is expressed in this Ensign article. Although it works out well for the three in the furnace, faith in God doesn’t always mean good and pleasant outcomes in this life. Sometimes it means dying horribly on the long cold wagon train to Salt Lake. The end that we are enduring to may be shorter than we think.

Once they are thrown into the furnace, note 3:25 where the KJV says “the fourth (person in the furnace) is like the Son of God.” It’s fairly unlikely that Babylonians would have an idea of what the future Son of God would look like, let alone any kind of Messianic views. The Hebrew simply says “appears like a son of god,” another way of saying “a divine being” or angel or deity. Something superhuman. This is why other translations simply read something like “has the appearance of a god” (NRSV, NET similarly) or “looks like a divine being” (JPS).

Esther–

I’ve done very little work with Esther, and had to do a little reading.

Esther is best read as a comedy. Rabbinic midrashim seem to have intuited this, and they add to the fun by their preposterous embellishments of the story and its characters, extending in the most unsubtle ways the farce or burlesque inherent in the book, with its bawdiness and slap-stick humor…. The lavishness of the Persian court and the ten drinking banquets in the story add to the aura of comic excess. The misunderstandings between Ahasuerus and Haman in chs 6 and 7, the climax of the plot, produce belly laughs. All of these attributes are characteristic of low comedy.

The story’s plot is structured on improbabilities, exaggerations, misunderstandings, and reversals. Esther keeps her identity hidden although her relationship to Mordecai the Jew was known; an insignificant Jewish minority kills 75,000 of its enemies; Haman erects a seven-story stake for impaling his enemy. The characters are caricatures. Ahasuerus is a buffoon, never sure quite what to do, completely at the mercy of his ministers and servants, giving away his power without a thought. Haman is an erratic egomaniac, with wild mood swings, concerned only for his own honor and his enemy’s disgrace. Even the heroes, Mordecai and Esther, seem one-dimensional and unrealistic. In fact, nothing about the events of the story is realistic, and therefore attempts to read history from it are misguided. The setting of the Persian court is authentic, but the events are fictional. There was no known Jewish queen of Persia. Moreover, the Persian empire was tolerant of its ethnic minorities and is an unlikely place for an edict to eradicate the Jewish population.- Jewish Study Bible, 1st edition

While “nothing about the events of the story is realistic,” the setting is much more so. Traditional arguments for a strictly historical genre of Esther have looked at the background to argue that an accurate setting implies a historical genre as well as historical accuracy. It’s not so simple, however.

On what grounds is a story to be judged fictional? Because it is easier to accept a patently unrealistic story, fictionality was sometimes determined by whether or not the events of the story could have happened or by whether the story seemed realistic. [Both of those criteria are problematic.] But to judge a story’s historicity by its degree of realism is to mistake verisimilitude for historicity. Verisimilitude is the literary term for the illusion of reality. Just because a story sounds real does not mean that it is. Realistic fiction is just as fictional as nonrealistic fiction. Among the leading arguments for Esther’s historicity are that its setting is authentic and that its knowledge of Persian custom is detailed and accurate. But this realistic background proves nothing about the historicity of the story, as our aforementioned commentators were well aware.- Adele Berlin, “The Book of Esther and Ancient Storytelling” Journal of Biblical Literature 120/1 (2001): 3-14

What value is Esther? For LDS, I think it’s useful because it is one of few stories centered on women in the Bible. For Jews, it explains (probably fictionally, as with many etiological stories) the origins of Purim. It also has

a serious side, and an important function as a Diaspora story, a story written about and for (and perhaps by) Jews of the Diaspora. As such, it promotes Jewish identity, solidarity within the Jewish community, and a strong connection with Jewish (biblical) tradition. It is more centered on the Diaspora than most Jewish works of its time; it does not refer to the land of Israel (other than the mention of the exile of Jehoiachin) or to the Temple. It addresses the inherent problems of a minority people, their vulnerability to political forces and government edicts, their lack of autonomy, and their dependence on royal favor and on the sagacity of their own leaders. More specifically, Haman’s false claim about the Jews is a prototype of anti-Semitism, which must have been familiar enough to resonate with the book’s original audience.- The Jewish Study Bible

As always, you can help me pay my tuition here, or you can support my work through making your regular Amazon purchases through the Amazon links I post. You can also get updates by email whenever a post goes up (subscription box on the right). You can also follow Benjamin the Scribe on Facebook.