Part Five: Dynamic Tensions

Some of us embrace this crazy jumble of influences and cultural tensions. Others believe that this mishmash, at best, creates a watered-down homogeneous hodgepodge of unclear and inconsistent beliefs; and at worst, fosters cultural appropriation.

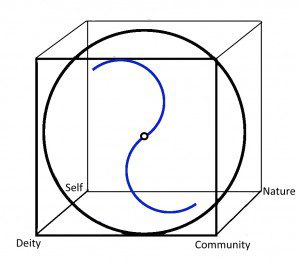

John Halstead’s “four centers” might give you the impression that Paganism is a bunch of disparate groups with some views that overlap, firmly encamped in different sections. Of course, my experience (which, I’m sure, is similar to yours) is that Paganism is a constantly churning whirlwind of dynamic tensions. I think that rather than picturing Paganism as a square, we might do better to visualize it as a cube, with a sphere inside it that swirls like a spiralling, changing storm.

Here are some of the high and low pressure areas that drive the winds:

Syncretism vs. Fundamentalism

I think we can collectively agree that Paganism’s roots have always been . . . eclectic. But just as we really mean “ceremony” when we say “ritual” and “altar” when we mean “shrine,” we say “eclectic” when we really mean “syncretic.”

Syncretism is “the attempted reconciliation or union of different or opposing principles, practices, or parties, as in philosophy or religion.”[xiii] Afro-Diasporic faiths are often used as examples of “syncretic religions.” Consider Voodoo’s unique mixture of Yoruban and Catholic elements, blended with a heavy dose of First Nations spirituality and Western occultism. To an outsider it could look as though there’s no rhyme or reason to it at all; just a bunch of weird charms and incompatible mythologies grafted onto one another.

And of course this is exactly the same sort of criticism that is often levelled against Neo-Paganism, Wicca and the so-called “Wiccanate” Paganisms. The critics sometimes call it “smorgasbord Paganism.” Sometimes I even think they’re right. The danger of an eclectic religion is that it can seem to have no unifying elements and no core principles, and a practitioner who doesn’t want to apply herself might take a sip from each glass without ever really understanding any of the rich and complex vintages they represent.

Then again, I’m not sure this is a bad thing. In Wicca every one of us is a priest or priestess, but that was because Gerald Gardner believed that Wiccans were maintaining the traditions of the Pagan priesthood in secret, and that there would again come a time when the witches would be clergy and Paganism would come out into the open to embrace lay worshipers.[xiv] The truth is that not all of us are called to the commitment required of clergy. And I don’t see why we should have to be. There’s a difference between not needing intermediaries between us and the divine, and taking on all the responsibilities of clergy. I have given my life to this calling, but people can be faithful and follow other callings. And in no other branch of Paganism is this expectation part of what you sign up for.

Another criticism of syncretic faiths, which probably isn’t unfair, is the risk of cultural appropriation. I think it’s important that those of us who embrace a syncretic path try to remember where the stuff we steal comes from. If we can’t give it the same meanings and associations that the culture of its origin gave to it, we should acknowledge that and not try to claim otherwise.

Syncretism is, in my opinion, a core value of Wicca[xv]; and if you don’t believe me, I’ll just point out that the original “Wiccan pantheon” included Greek, Roman, Celtic, Norse, and Sumerian deities, along with a handful of deified figures of folklore and Jungian psychology, and leave it at that. I think for us, that’s a good thing. Wiccan and Neo-Pagan traditions should stop apologizing for it and instead admit that we find this desirable.

But on the other side of the coin are the more “traditional” of our traditions; Reconstructionist and Traditionalist Movements, and also, some forms of Atheopaganism. This group might also be thought to include Wiccan traditions that insist that British Traditional is the only “real” Wicca and pretend that Hutton[xvi] never existed. They might resent the use of the word “fundamentalism” because we associate it with a certain type of Christian that we often find ourselves in conflict with. But fundamentalism means “strict adherence to any set of basic ideas or principles.”[xvii] In a religious context it also means to take a myth literally (such as the existence of the gods, or whether or not nine million European women were actually burned as witches). That comes back to our question: do the gods exist, and if so, what are they?

The fundamentalist traditions share the belief that we should go back to a more “pure” form of Paganism. We should stick to one pantheon (or avoid “gods” entirely). We should try to get back to what our ancestors were doing. If we can’t imitate their ceremonies and devotionals precisely, then we should at least try to understand and worship the Pagan gods in the ways our ancestors understood them. They demand historically-accurate research, proper adherence to ritual forms, and scientific documentation.

I don’t believe that anyone is actually rediscovering the real “Old Religion.” We are not looking at Paganism in the same way, no matter how “historically accurate” we try to be. We could all be SCA-attending homesteader heathens living in a longhouse, weaving our own clothing and growing our own food, but we would still be products of the modern era, with modern technology and modern ethics and modern laws and culture. No matter how precisely we re-create a faith, we are not the Pagans of the Ancient World and we never will be, and therefore we cannot possibly understand their gods and their faith in the same ways that they did. It might be educational, fun and meaningful to put on a traditional blot, however.

If I have to choose between these tensions, I choose syncretism. But a lot of good comes out of going back to the fundamentals as well. I think it’s essential that we have accurate research and that we constantly question and challenge our beliefs; how else do we know if they’re any good? I resent it when someone claims that it’s a fact because “it is known.” (Do you remember Season 1, Game of Thrones? Daenarys’ handmaiden – “it is known?” I have no patience for that stuff.) I also think it’s important that we maintain what traditions we’ve established. It’s especially important for our “New Old Religions” to maintain a sense of continuity and to build group identity. And as I said at the outset, I do believe that there are such things as “core Pagan values.” Without people willing to define limits, we’ll never learn what those are.

The modern Pagan movement is not a special snowflake. The truth is that religious systems do not spring fully-formed out of the forehead of Zeus like Athena and we humans do not exist in vacuums. The reality is that we all stand on the shoulders of giants. We need to remember where we came from so that we know where it is that we’re going.

Fundamentalism can lead to dogmatism, something that we Pagans claim to dislike. Another flaw in fundamentalism is that it tends to be very tribal, and while tribes are probably the most natural human social structure there is, it’s a thin line between tribalism and prejudice. And a third flaw is that it can lead to inflexibility and becoming hidebound.

Gnosis vs. Orthodoxy

Speaking of becoming hidebound, the second set of high and low pressure areas to generate wind run along an interesting axis that you might not expect.

We claim that Paganism has no dogma. We claim that it’s orthopractic; that is, it’s based in practice, not dogma. Perhaps that was once true when everyone was Wiccan, but it isn’t anymore. It isn’t even true of Wicca. We have no uniform rituals or teachings except within the confines of a tradition, and even then we have a lot of variation.

Gnosis is “received knowledge.” It’s when someone has a moment of mystical revelation that changes everything. In some religions they have a name for those who have received Gnosis: prophets. We have names for them too: we call them shamans, seers, high priestesses or hedge-witches. In other words, for us they’re by no means uncommon.

And some call them idiots, nutbars or liars, because as far as they are concerned, what Gnosis really means is “making stuff up.” The critics have even given their statements a special pejorative: UPG “unsubstantiated personal gnosis.”

We hesitate to use the word “orthodox,” which means “sound or correct in opinion or doctrine, especially theological or religious doctrine.”[xviii] But we have it all the same. For example, another Patheos writer, Asa West, was recently torn apart on her blog for saying that the Morrighan had given her a message of peace for Israel[xix] (and she’s Jewish, before anyone wants to take a side on that.) People couldn’t imagine that a bloodthirsty war goddess would give any kind of message of peace. But as Asa pointed out, the Morrighan is also a goddess of sovereignty, and perhaps that’s the aspect that she was dealing with.

Okay, quick survey: does Loki have red or black hair? Hands up for red? Hands up for black? Hands up for “who cares and why am I wasting time with this stupid and pointless question?” Because people get into rabid frothing arguments about it over the internet, that’s why.

We used to run into British Traditional types a lot in the 90s who were like this. The reason why we have the terms “eclectic Wicca” and “Neo-Pagan” is because every time somebody spoke up who couldn’t provide a line graph of their initiatory lineage, this obnoxious minority would show up to tell us that we were doing it wrong. We got tired of being told that so we started calling ourselves something else. Also the term “fluffy bunny” was coined by the same group to deride anyone who wasn’t one of them; along with IRAB (I Read a Book). Perhaps it’s a great irony that these days if you mention that you’re Wiccan, you’ve immediately got five “traditional witches” who are telling you that you’re the “fluffy bunny.”

This kind of polarizing pigheadedness seems like a bad idea to me. But on the other hand, we don’t respect our teachers, and that’s a bad idea too. Do you remember me saying that at the beginning of a thing, even the smallest changes can have unintended consequences? One of the unintended consequences of our ethic of anti-establishmentarianism is to rebel against anything that looks like an establishment, even in our own ranks. We actively try to destroy any sort of organization that does appear and coven politics are kind of like living as a drow house noble; the Matron Mother has to expect that her daughter, a.k.a. the Coven Maiden, is going to rise up to try to replace her.[xx]

There are some of us who have gone so far out of our way not to listen to anyone else and to march to the beats of our own drummers that we have to keep reinventing the wheel. I’ve been actively involved in Pagan community for . . . twenty-two years? Listen guys: you’re not the first ones to write inclusive Great Rites, you didn’t discover sex magick and witches have been making flying ointment in England for a long time. It’s like teenagers: they always think they’ve invented sex.

I’m pretty sure that between gnosis and orthodoxy, I fall somewhere in the middle. I see the need for both and I try to create and support structures that make room for both.