As I understand the Bible, we’re supposed to love others unconditionally. I understand this to mean not only regardless of what others might have done to us, but also regardless of who they are. I’ve heard countless sermons on this, and, frankly, I probably need to hear–and enact–many more.

Social psychologists have studied altruism–helping other people in need–and it turns out that there is systematic variation in who we are willing to help. One of the factors has been termed “deservingness.” That is, are people worth our assistance. Already, from the language of the concept of deservingness alone, we can tell that it’s at odds with the Christian definition of love.

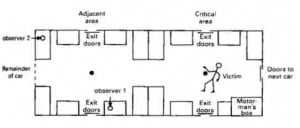

The impact of deservingness on helping others has been documented in various studies, and a classic study was conducted by my Ph.D. mentor, the late Irving Piliavin, and his wife Jane, in 1969. In a very clever design, four researchers would ride the subway in New York, and one of them would stagger and fall down while the other three would covertly take notes on what happened. The person who fell would stare at the ceiling until the subway got to the next stop, and then, if now one helped them up, they slowly got up and went on their way. Here’s where it gets interesting. Sometimes, the person falling down had a cane, implying that they fell due to some sort of illness or disability. Other times, however, they smelled like alcohol and had a bottle in a brown paper bag in their hand, implying that they fell down drunk.

The good news? There was lots of helping behavior. The Piliavins did this study 98 times, and in 81 of the situations, somebody came forward to help. That’s good news (and it would be interesting to replicate the study today to see how base levels might have changed).

The big finding, though, was that helping behavior varied considerably by the perceived deservingness of the victim. When someone with a cane fell down, they were helped 95% of the time; however, when someone with a bottle fell down, they were helped only 50% of the time.

Importantly, the deservingness effect only made a difference in terms of whether the first person helped. Once one person helped, then others joined in at equal rates, regardless of whether there was a cane or a bottle.

We see this appeal to deservingness a lot with Christian charities. They collect money to do good in the world, often, by emphasizing the deserving victim status of who they are helping. For example, World Vision, which is a fine charity, and one that my wife and I have supported financially, tells the stories of children placed in terrible situations due to no fault of their own. On the website today, World Vision tells of a child named “Esnart.” “Esnart has never wore shoes or clean clothes, and the cracks on her feet caused an infection that could have been life-threatening without World Vision’s intervention.” We can “donate now to help provide clean clothing and medication to children like Esnart.”

This emphasis on deservingness underscores an implicit assumption that there are certain types of people that we should help and certain types that, well, are less important. The key issue seems to be whether the person in trouble did anything to bring about their situation (which we might perceive as “bad”) or if they are “innocent” victims of larger circumstances. Note, this distinction pushes us away from helping and into judgement.

Obviously I’m not saying that we should not give money to starving children. (That would be pretty dumb, even for a sociologist). Instead, maybe we should be just as likely to reach out to people whose lives are ruined due to their own inadequacies, even if they are moral inadequacies. I think that we should be just as loving and giving to prisoners as to their children, to sex offenders as to victims, to adults who have made bad choices as to children who have had no choice.

Jesus exemplified this with whom he hung out with and helped–prostitutes, white-collar criminals, and so forth–causing no end of scandal to the proper religious authorities.

I wonder if our emphasis on helping the deserving is pushing us toward how the authorities acted and away from Jesus’ example?

Extrapolating from the Piliavin study, if one person reaches out to an undeserving person/ population, then perhaps perhaps others will follow that person’s lead, and the undeserving person/ population will receive aid at levels otherwise reserved for the deserving.